Art & Exhibitions

Peter Hujar’s Lesser-Seen Early Works Take the Spotlight at the Ukrainian Museum

"Rialto" features the photographer's early body of work, from 1955 through 1969.

The new show, “Rialto,” at the Ukrainian Museum in New York spotlights the first formative decade of Peter Hujar’s career. It’s an apt venue: the late photographer was raised by his Ukrainian grandparents on a farm in New Jersey before moving to the city, where he lived in an old theater less than a block from the museum. Hujar became an East Village fixture, one familiar to Peter Doroshenko, the institution’s director.

“I met Peter at a dollar-slice pizza when I was a student in 1985, and it was a two-minute encounter,” he told me. “Then I saw him six months later on St. Marks when I was walking down the street and he said hello. I realized who it was and I thought, well, I’ll contact him later. But he passed six months later, so there was never a later.”

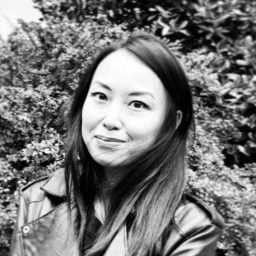

Installation view of “Rialto” at the Ukrainian Museum. Photo: Min Chen.

Doroshenko believes Hujar must have visited the museum, even if the Ukrainian diaspora was perhaps unaware of his work or presence. An exhibition, he said, made sense, particularly one that centered on Hujar’s earliest body of work, from 1955 through 1969, which is likely lesser known.

“Rialto,” which means meeting place, alludes to Hujar’s Second Avenue studio, at which his fellow artists and downtown denizens often congregated. But it also befits an exhibition of some 75 photographs showcasing Hujar’s range and roving eye. Though the photographer is now recognized for his images of New York’s gay and downtown subcultures, the show is a reminder that he also captured children and animals, street scenes and country roads, famous faces and nameless corpses.

Peter Hujar, Drag Ball, Hotel Diplomat (1) (1968). Courtesy the Ukrainian Museum, New York. © The Peter Hujar Archive – Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

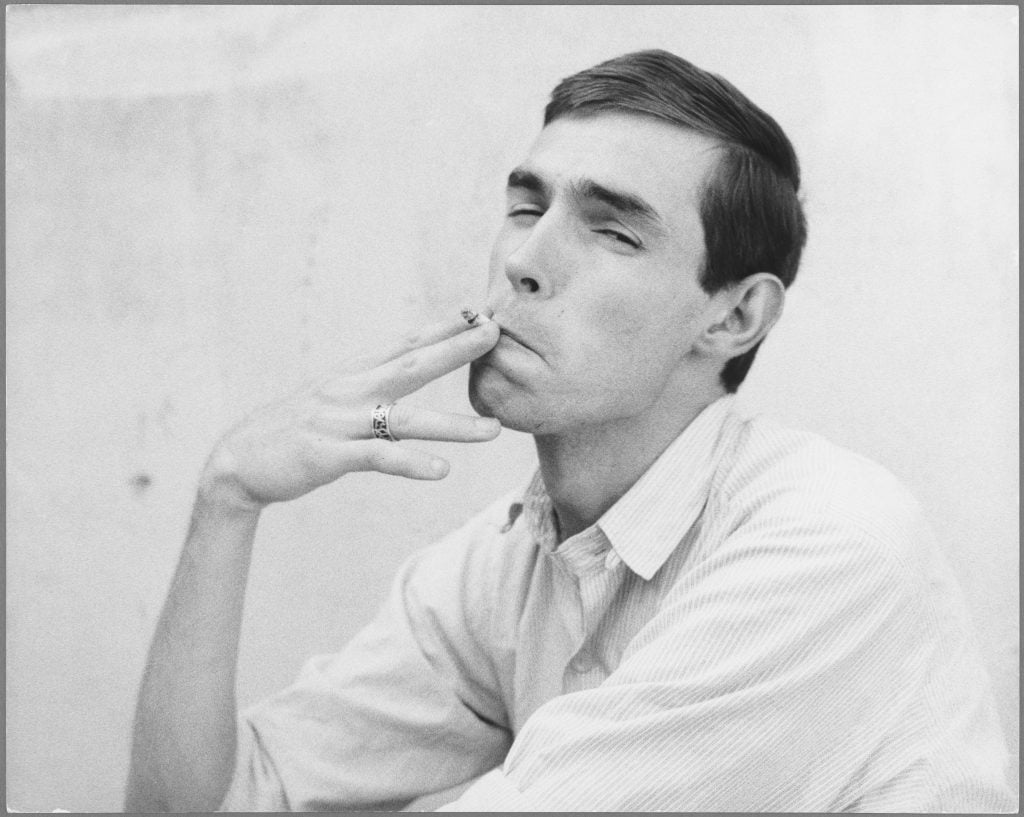

At the heart of the exhibition are three series of original prints: Hujar’s images from his 1957 visit to a Southbury, Connecticut school for children with learning difficulties; his 1958 trip to Florence, Italy; and his tour of the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo in 1963. The settings vary, but the photographer’s tender gaze runs throughout. None of the human subjects, Doroshenko pointed out as we walked through the show, wear a “photo face.”

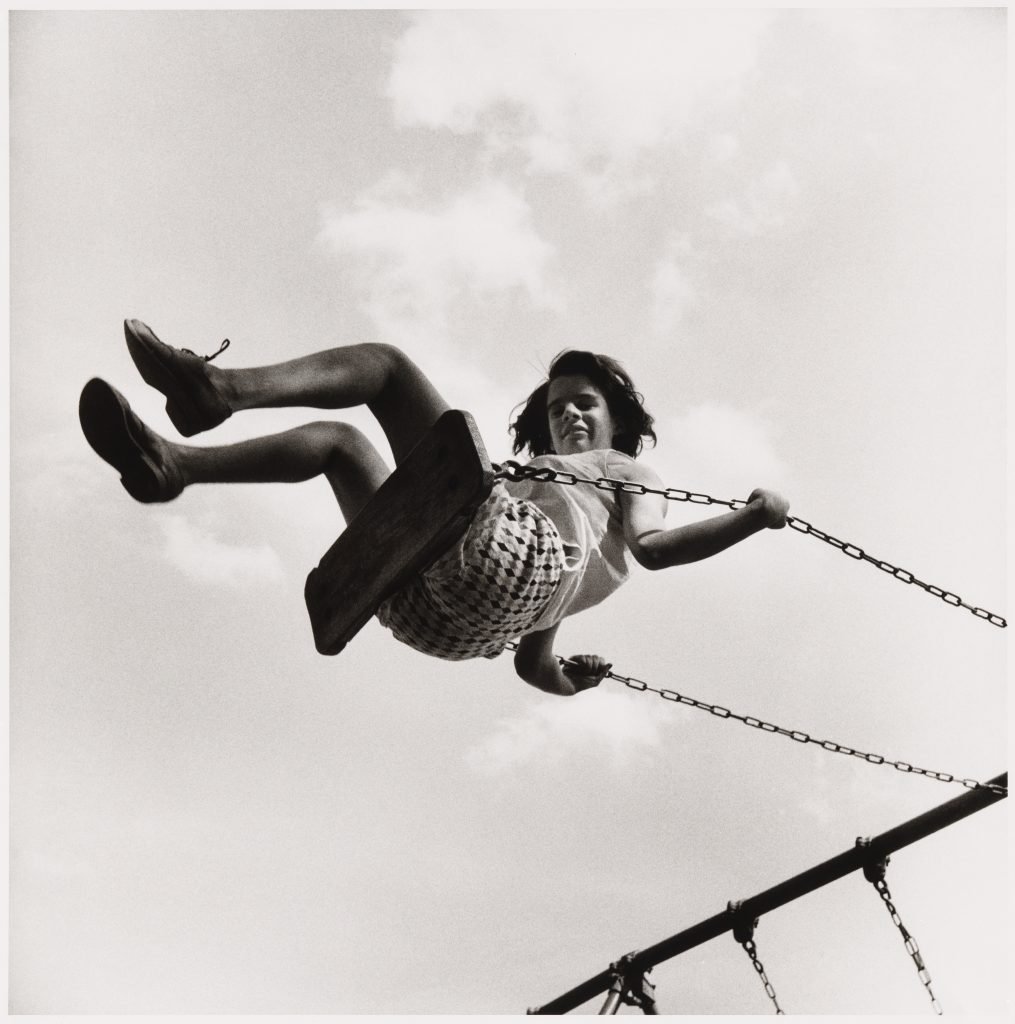

Peter Hujar, Girl on Swing, Southbury (1957). Courtesy the Ukrainian Museum, New York. © The Peter Hujar Archive – Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

“Peter was very good at capturing that moment,” he said. “But to catch that moment, he was also very good at making people feel comfortable where they forget that he’s taking their picture. It was very much about creating an atmosphere or a dialogue and then getting that particular picture.”

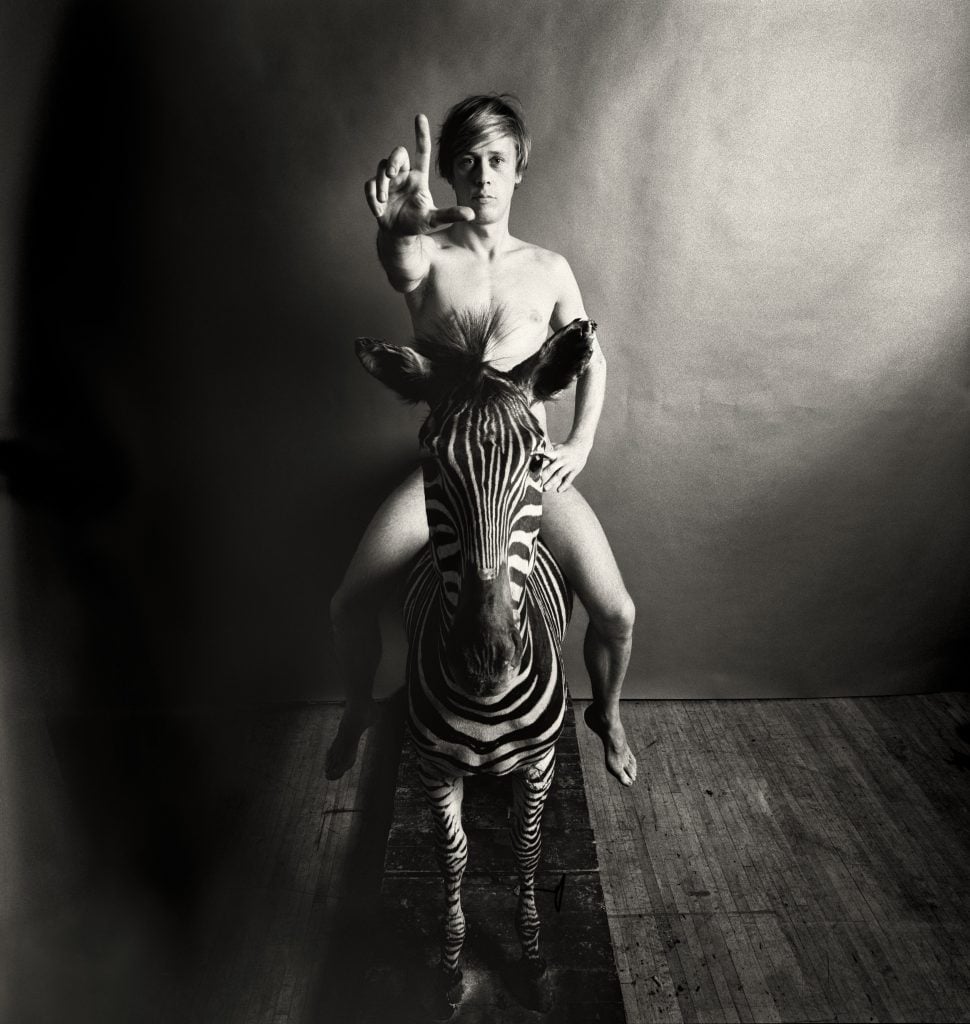

Also included in the show are Hujar’s spontaneous shots of street scenes—a cat in a bodega, a crowd on Times Square—and portraits of artists including Iggy Pop, Jackie Curtis, and his partner Paul Thek.

Peter Hujar, Paul Thek on Zebra (1965). Courtesy the Ukrainian Museum, New York. © The Peter Hujar Archive – Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

While Hujar’s later work from the 1970s and ’80s may be better known, Doroshenko locates a seed in these early pieces. He noted Hujar’s strict Ukrainian upbringing (he didn’t speak English until he entered kindergarten), as much as how he entered the field of photography without any formal training. These experiences, he said, “created those vectors of series and control” and influenced “how he positioned himself as a photographer.”

“This exhibit shows that throughout his work processes, his interests and his engagement with people and different situations, there were things that people would never expect,” he added. “Photographers like Diane Arbus had a particular kind of hyper-focus; Peter had that but not this tunnel vision. There were always surprises.”

“Rialto” is on view at the Ukrainian Museum, 222 East 6th Street, New York, through September 1.