A long-planned traveling Philip Guston retrospective has been postponed for three years over concerns about how the work will be received amid heightened racial tensions and ongoing protests both in the US and abroad.

This is actually the second delay for the show, titled “Philip Guston Now,” which was announced in June 2019. It was originally set to open June 7, 2020, at National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, before traveling to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Tate Modern in London; and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Those dates were pushed back to July 2021 due to extended museum closures. Now, curators plan to completely rethink the show ahead of a newly set 2024 opening.

“The racial justice movement that started in the US and radiated to countries around the world, in addition to challenges of a global health crisis, have led us to pause,” the four museums said in a joint statement posted on the National Gallery website on Monday. “We feel it is necessary to reframe our programming and, in this case, step back, and bring in additional perspectives and voices to shape how we present Guston’s work to our public. That process will take time.”

At issue are Guston’s paintings that feature hooded Ku Klux Klan figures. The exhibition was set to have featured 25 drawings and paintings from that body of work, representatives from the museum told Artnet News.

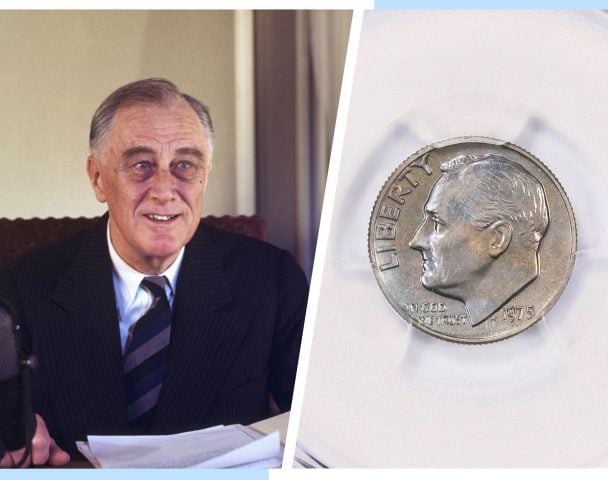

Philip Guston, Painting, Smoking, Eating (1973). Courtesy of the Stedelijk Museum/©the estate of Philip Guston.

“Because they are an important part of Guston’s oeuvre, we sought to find a way to include them while being mindful of the context that would be required for viewers to better understand why Guston made them,” said a joint email from seven representatives of the four museums. “As issues of race and social justice have become increasingly part of public dialogue over the last several months, it became apparent we needed to rethink our interpretation of these works.”

The postponement has been met with opposition from Musa Mayer, the artist’s daughter and head of the Guston Foundation. “Half a century ago, my father made a body of work that shocked the art world,” Mayer said in a statement. “Not only had he violated the canon of what a noted abstract artist should be painting at a time of particularly doctrinaire art criticism, but he dared to hold up a mirror to white America, exposing the banality of evil and the systemic racism we are still struggling to confront today.”

Regarding Guston’s Klan figures, Mayer said, “They plan, they plot, they ride around in cars smoking cigars. We never see their acts of hatred. We never know what is in their minds. But it is clear that they are us. Our denial, our concealment,” she added. “My father dared to unveil white culpability, our shared role in allowing the racist terror that he had witnessed since boyhood, when the Klan marched openly by the thousands in the streets of Los Angeles.”

The art historian and curator Darby English told the New York Times that the decision to postpone the show was “cowardly and patronizing, an insult to art and the public alike.” Guston’s paintings were “thoughtfully created in identification with history’s victims,” English said, adding that “it should be part of one’s attitude to see them as opportunities to think, to improve thinking, to sharpen perception, to talk to one another,” and not “to grimly proceed with one’s head in the sand, avoiding difficult conversations because you think the timing is bad.”

Guston himself called the works self-portraits. “I perceive myself as being behind the hood,” he was quoted in the 2019 publication MoMA Highlights: 375 works From the Museum of Modern Art New York. “I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. What would it be like to be evil?”

Philip Guston, Untitled (Two Hooded Figures) (1969). Courtesy of Christie’s Images, Ltd.

Robert Storr, who this month published a biography of the artist, Philip Guston: A Life Spent Painting, called the museums’ decision “an abject failure of imagination and nerve.”

“Now that resurgent forces of nativism and bigotry threaten the very fabric of American society is the moment to revisit Guston’s oeuvre,” Storr told Artnet News in an email. “Nevertheless, museological cowardice and malpractice have deprived us of the opportunity to reconsider the vexed social dimensions of art, and of our conflicted reality through the prism of the moral and political subtleties, purposefully provocative ambiguities, and searing satire of Guston’s prescient and profoundly disturbing work as a whole. This is an epic betrayal of art, of the artist and, most of all, of the public to which this institutional cock-up does a disservice at every turn, on every level.”

Museums have increasingly faced criticism in recent years for exhibiting work that addresses issues of racial violence. The 2017 Whitney Biennial sparked controversy for including Dana Schutz’s Open Casket, a painting of Emmett Till, whose brutal 1955 lynching made headlines when his mother insisted on an open-casket funeral. Detractors accused Schutz, who is white, of capitalizing on Black suffering, and called for the painting’s destruction.

More recently, the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland canceled an exhibition of Afro-Latino artist Shaun Leonardo’s drawings of victims of police brutality due to community objections. The museum’s director, Jill Snyder, apologized and resigned. (The exhibition is now on view at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art and will travel to the Bronx Museum of the Arts in January.)

Philip Guston, Passage (1957–58). Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston/©the estate of Philip Guston.

The upcoming exhibition was to have been Guston’s first US retrospective in 15 years, including some 125 paintings and 70 drawings.

Websites for the show at its first two venues, the National Gallery and the Tate, have been taken offline since the postponement announcement. Neither museum directly addressed the KKK imagery. The Tate mentioned Guston’s ’70s-era “paintings populated by cartoonish figures,” noting that they were not initially well-received by critics, but “established Guston as one of the most influential painters of the late 20th century.”

The museums will still publish the catalogue for the exhibition as originally planned, with essays from the four curators: Harry Cooper, Alison de Lima Greene, Mark Godfrey, and Kate Nesin.

Godfrey, senior curator of international art at the Tate Modern, has spoken out against the postponement on Instagram, reports the Art Newspaper. “Cancelling or delaying the exhibition is probably motivated by the wish to be sensitive to the imagined reactions of particular viewers, and the fear of protest,” he wrote. “However, it is actually extremely patronizing to viewers, who are assumed not to be able to appreciate the nuance and politics of Guston’s works.”

The museums’ joint statement says that they “remain committed to Philip Guston and his work,” and that they hope to stage the show at a time when “we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.”

That will involve bringing in “additional perspectives and voices to shape how we present Guston’s work at each venue,” the museum representatives told Artnet News. “This will be a complex and layered process that goes beyond rewriting labels, but takes into consideration the ways in which we communicate the production of this work in its time and the reception by audiences today.”

Mayer believes that moment is already here. “These paintings meet the moment we are in today,” she said. “The danger is not in looking at Philip Guston’s work, but in looking away.”