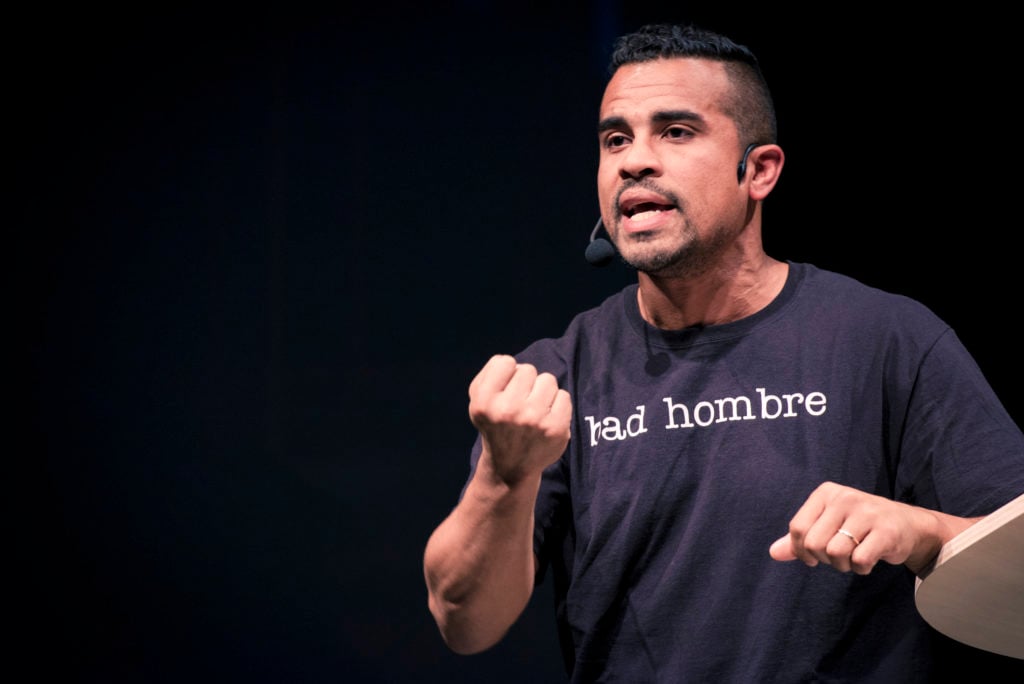

This past June, at the height of the protests surrounding the killing of George Floyd, an exhibition of artist Shaun Leonardo’s drawings depicting the deaths of unarmed Black and Latino men at the hands of police was set to go on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland. But instead, the museum canceled the show amid a public uproar that led, ultimately, to the resignation of the museum’s director.

Now, two institutions have stepped up to mount the artist’s previously canceled show. “Shaun Leonardo: The Breath of Empty Space” will go on view this Wednesday at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art before heading to the Bronx Museum of the Arts in January.

“After grave mishandling of communication regarding the exhibition, institutional white fragility led to an act of censorship,” Leonardo said in a statement in June, referring to the MCA Cleveland’s cancelation of his show. He explained that he was given no voice in the decision, nor was he allowed to discuss the issue with members of the community, who, according to the museum, feared the artwork “could stir trauma, leading to pain and harm.”

Shaun Leonardo, Michael Brown (2015). Courtesy of the artist.

Jill Snyder, then the director of the MCA, stepped down on June 19. The announcement from the museum did not acknowledge the incident.

Indeed, the optics of the museum’s decision were bad. But the reasons behind the choice painted a more complicated picture. Among those who opposed the show was Samaria Rice, whose son Tamir was killed by police in 2014, and local artist and activist Amanda King, who has been working with Rice to establish the Tamir Rice Afrocentric Cultural Center in Cleveland. The two have been vocal in their disapproval of artwork that appropriates Tamir’s image—such as two drawings in Leonardo’s show which depict the young boy at the gazebo where he was shot.

Shaun Leonardo, Freddy Pereira (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

Rice issued a cease-and-desist letter to the artist urging him not to exhibit the two works and to remove images of them from his website.

“[Rice] is very concerned that work like this reduces who Tamir was to a horrific moment that alone does not define him,” King told Artnet News in July, alluding to Leonardo’s work.

For the show opening this week at MASS MoCA, Leonardo will withhold the two drawings of Tamir Rice. In the place of those artworks, the museum will paint two black squares that occupy the same dimensions.

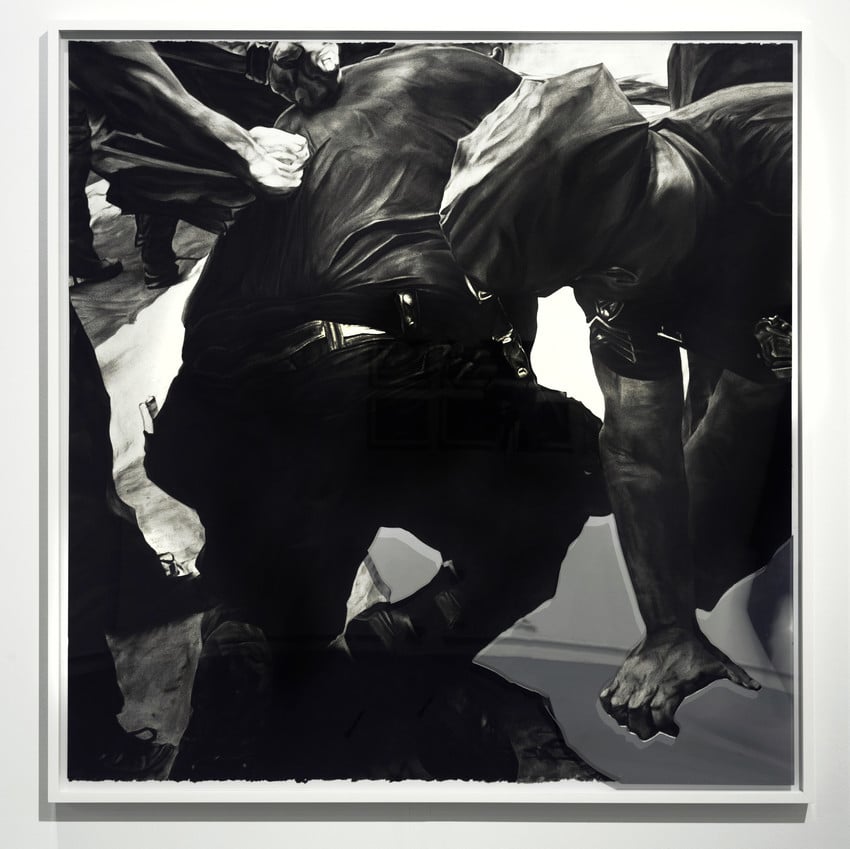

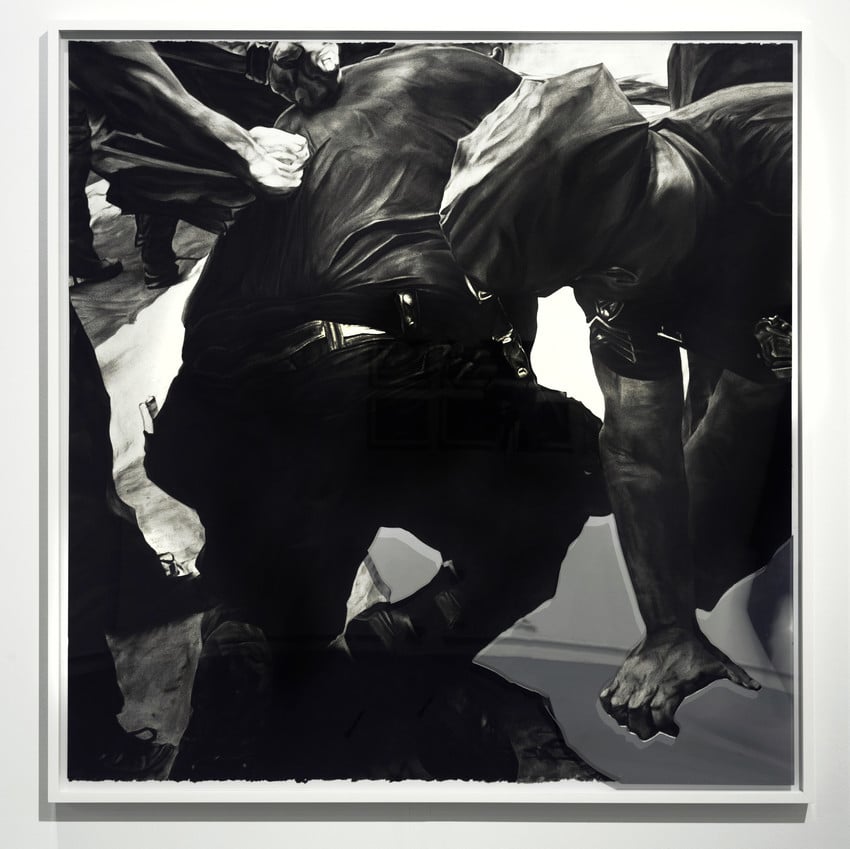

Shaun Leonardo, Rodney King (2017). Courtesy of the artist.

“That’s the space in the exhibition where we acknowledge the various areas of debate that have emerged around the work,” Leonardo tells Artnet News.

The goal, he goes on, is to shift viewers’ attention from the controversy to the issues contained within the works themselves—one of which is the way images are distorted through the channels in which they are shared.

“What has been aired,” he says, referring to issues raised in Cleveland, “was not due to a physical experience with the work, which I think is critical to acknowledge. It was about the perception of the exhibition, my practice, and, I should say, my personhood.”

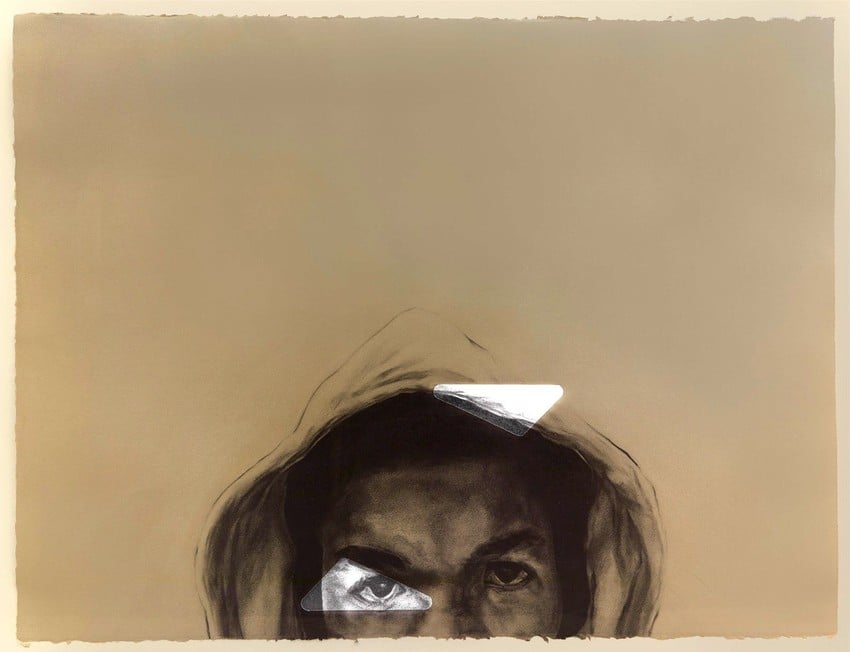

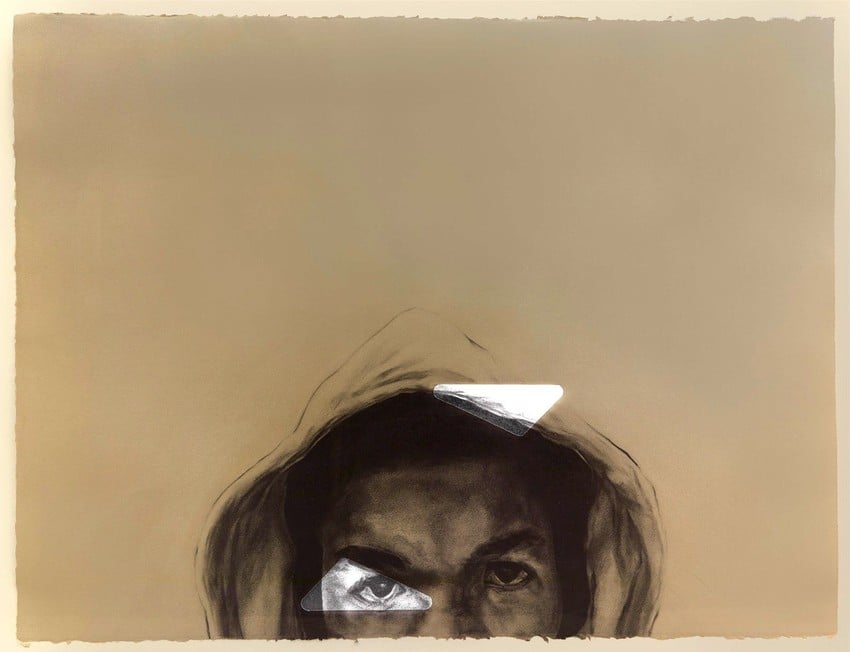

Shaun Leonardo, Trayvon (2014-17). Courtesy of the artist.

Still, Leonardo is not shying away from the controversy in Cleveland or the questions raised therein. The two drawings of Tamir Rice will be included in the Bronx Museum show next year.

“I still believe wholeheartedly that this work is necessary,” he says. “It’s important to distinguish these drawings away from a re-presentation of the traumatic images as they’ve been circulated in the media and to look at them as a different kind of opportunity.”

“They allow for a different type of viewing that causes us to question how we receive and internalize images in the first place. It’s through that process that we gain information that would otherwise be missed.”