People

Photographer Alec Soth Made His Name Photographing Middle America. But ‘Middle America’ Isn’t What It Used to Be

We spoke with the Minneapolis-based artist, who has four concurrent shows around the world and a new monograph to accompany them.

We spoke with the Minneapolis-based artist, who has four concurrent shows around the world and a new monograph to accompany them.

Taylor Dafoe

Alec Soth’s best-known bodies of work mine the relationship between Middle America and the people who called it home. Sleeping by the Mississippi (2004), the project that put Soth on the art world map—and into the 2004 Whitney Biennial—had him traversing the Mississippi River with his lens trained on solitary subjects and sparse, post-industrial landscapes. His last large-scale project, Songbook (2015), found the Minnesota born-and-based artist acting like a newspaper photographer of yesteryear, traveling from one small American town to another, making black and white pictures of communal gatherings.

But “Middle America” is different now from what it was then. And so, too, is Soth.

For his newest body of work, I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating, the artist eschewed the geographic focus that had put him in the lineage of road-tripping photographers like Walker Evans, William Eggleston, and Stephen Shore. Instead, the new series is more open in format, and Soth, instead of looking for specific, local cultures, was simply seeking a personal connection. He found it everywhere: with strangers in the Ukraine; in small rooms in Warsaw, Poland; and even in his hometown of Minneapolis.

The pictures he made are now the subject of a new monograph, published by Mack, and four concurrent exhibitions at Sean Kelly, New York; Weinstein Hammons Gallery, Minneapolis; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; and Loock Galerie, Berlin.

Soth spoke with artnet News on the occasion of the exhibitions, explaining how his new body of work allowed him to come to terms with both the changing American landscape and the limits of photography.

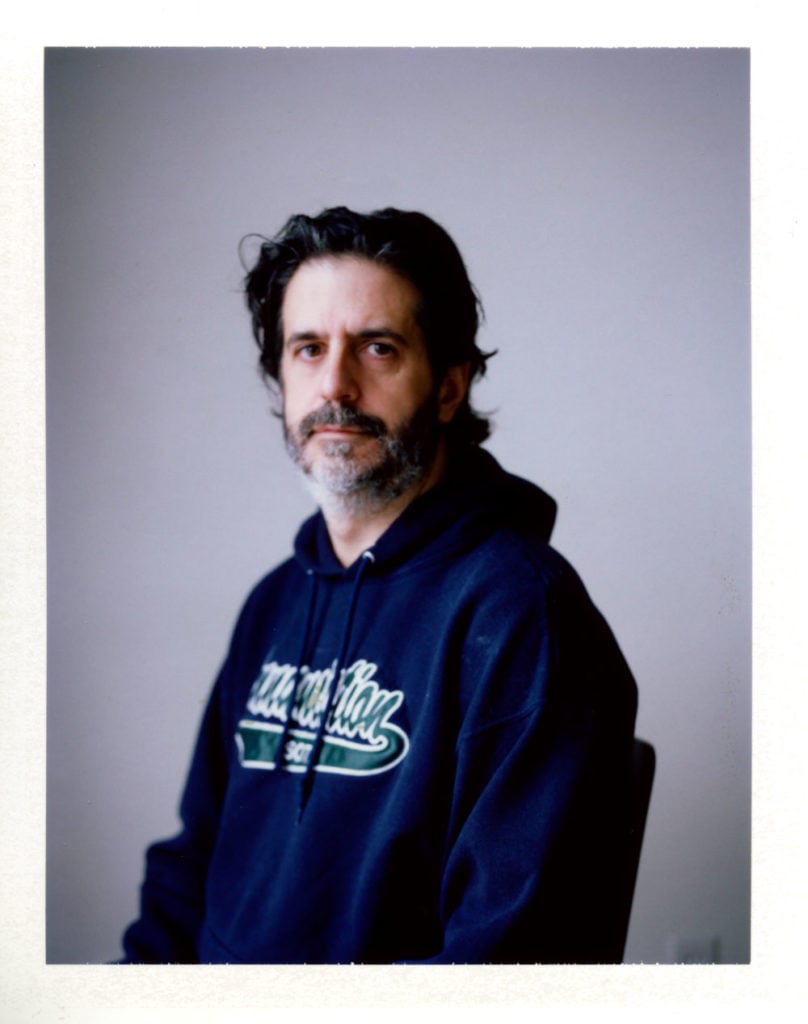

A self-portrait of Alec Soth (2018). Courtesy of the artist.

In a statement for one of your new shows, you say: “When I returned to photography I wanted to strip the medium down to its primary elements. Rather than trying to make some sort of epic narrative about America, I simply wanted to spend time looking at other people and glimpsing their interior life.” Why the urge to condense now?

I’m going to come at this from a totally different angle. Recently, the famous poet Mary Oliver died, and I really like Mary Oliver, even though it’s not always cool to like her. There was an interview with her just a couple of years ago where she talked about how her poems were getting shorter and shorter as she got older. I got that. If you look at the average length of poets’ writing over their careers, I bet they would be short in the beginning and then get longer and then get short again. I’m just guessing.

With my own work, I had a sense that I needed to return to the primary impulse of why I was taking photographs in the first place; I needed to declutter the whole enterprise. In the last few years, I did this project where I worked with teenagers and I think part of my motivation there was to touch upon what I felt like as a teenager and try to remember that. I think I just wanted to get back to the fundamental questions: Why did I love doing this in the first place? What is it? That’s what this body of work is about.

Do you feel like you were able to recapture that?

Absolutely. I went through a phase of not traveling, not doing jobs, and just sort of slowing down. That process of cleaning things out helped me get in touch with the basic motivation again. Now I’m doing a ton of traveling and photographing and editorial work, and I’m chasing after it again. But I feel renewed.

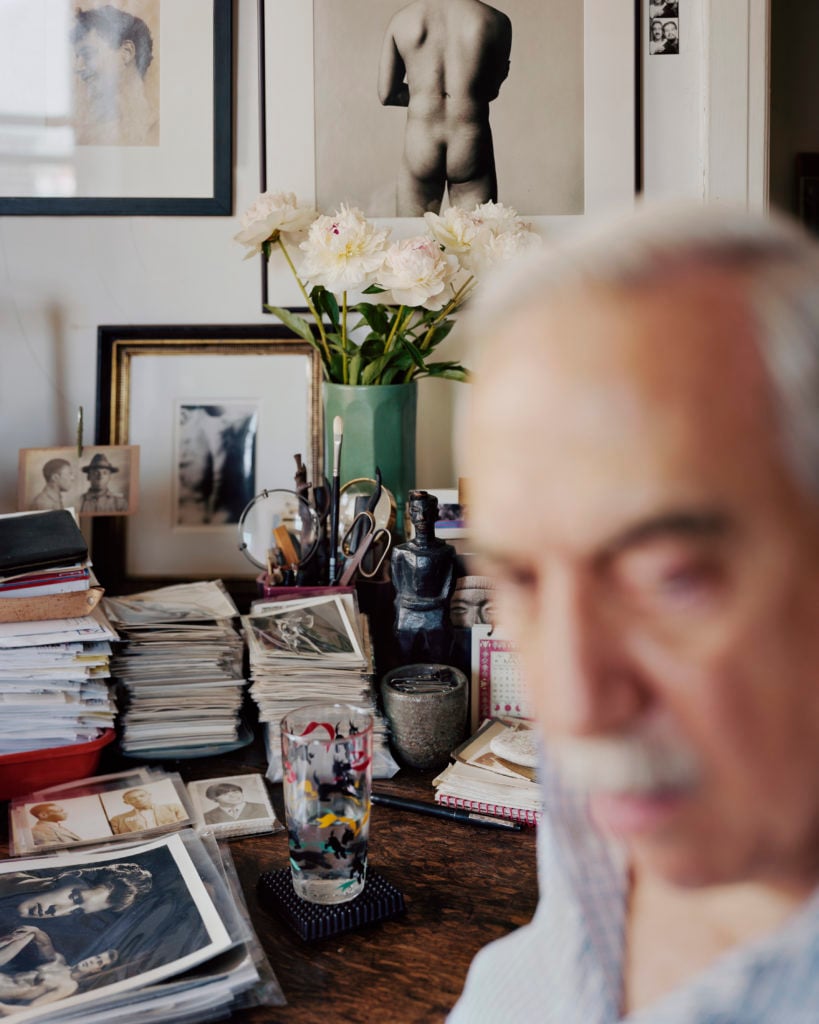

Alec Soth, Vince. New York City (2018). © Alec Soth. Courtesy of Sean Kelly, New York.

Much of your previous work was, in a sense, about Middle America. But a lot has happened in the last couple of years and our understanding of “Middle America” is much more complicated than before. To what extent did that play a part in your decision to divorce location from the new project?

I am a project photographer; I’ve worked that way for a long time. So I like to create some sort of narrative. I like to base it in a strange geography, have certain repeating motifs, do all those things that a project does. Because I do magazine assignments, I would get all these calls to photograph Trump’s America and all that. It was the last thing that I wanted to do, because I wanted just to make a human connection. And I didn’t want to be put in a place where I was judging. This project was the opposite of judging people—it was about trying to be open. So it was an intentional act to keep myself from repeating some sort of big, serious documentary project. What’s interesting, in retrospect, is how much you can feel that Trump world in Songbook, my last project, even though I wasn’t thinking about it in that way at the time.

How did you find the people with whom you could make a personal connection? And how did you achieve that when photographing them?

This is a hard question to answer because part of what I was trying to do was not to have a formula. I wasn’t trying to do what I’d done in the past, which was simply drive around and pluck people that I find interesting and curious. So this time, I decided to go somewhere, usually on an invitation—someone would invite me to give a lecture or whatnot—and I would find somebody in that region who could help me find other people. And like you, they would ask: “Well, what are you looking for?” At first I would say, “It’s hard to say. I’m looking for people with a certain kind of relationship to physical space.” Eventually, people would just send me photographs, and then I would respond and negotiate a time for a sitting in advance. The more pictures I made, the more I could show examples of other people that I’d photographed for this project. and thus show that I wasn’t looking for one particular age or gender or class or occupation.

Alec Soth, Leyla and Sabine. New Orleans (2018). © Alec Soth. Courtesy of Sean Kelly, New York.

In the early 2010s, many photographers were making formally experimental and self-reflexive work addressing digitization and the so-called “ocean of images,” while more “straightforward” or documentary-style work was out of vogue. But now it seems like the pendulum has swung back and there’s a very big interest in realism and portraiture again. What do you make of that?

That’s interesting. I did feel that push away from it, but I didn’t know that it has swung back. I think throughout the course of photographic history, this kind of thing has happened. There’s always been push and pull between abstraction and realism. Of course, that’s the case with the larger art world too—it is full of fashion trends. I know that’s part of the package, which is why I’ve always made work outside of that world. I don’t have total trust in the mechanics of the art world. I always make the analogy to musical genres. For me, some of the more formally playful work was like techno music. Me, I’m more of like a… I don’t want to say singer-songwriter, but it’s more in that terrain. [Laughs] And moods can shift, of course. You don’t want to listen to that—or any—kind of music all the time.

The name of the new book, I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating, is taken from Wallace Stevens’s poem “The Gray Room.” What about this poem, and that line in particular, drew you?

Sometimes Wallace Stevens is just perfect. This is one of those poems. It goes back to the original idea for the project: photographing in rooms. That sounds boring, but if your eyes are wide open and you look in just the average person’s room, you see all these visual delights. In this very short poem, Stevens enumerates all these different colors and textures, all these different kinds of beauty. And then there’s a person in there, another human being with all these hopes and dreams and fears and anxieties that we can glimpse, but will never totally know. I think Stevens is saying that it’s okay to be satisfied with that balance of beauty and mystery. I’ve really fought with the photographic medium at times, and sometimes I get incredibly frustrated that I can’t tell any more about the person I’m photographing. At other times, I’ve felt like all I’m doing is photographing emotional distance. But with this project, I felt more at ease with this balance of revelation and mystery.

It’s surprising to hear that you’ve fought with the medium. You seem like someone who is very comfortable with what photography is—the way it operates, its limitations, its history.

No, I’ve always fought against it. For me, it often comes down to narrative. Narrative is just the most powerful thing in the world—we all love stories. Photography is fundamentally non-narrative. So I was always fighting that and always trying to create quasi-narrative projects. And that’s not to say that I won’t have those battles again. But for me, this project was about coming to terms with that, saying, “Okay, this is what the medium is, and I’m going to embrace it.”

See more works from I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating below.

Alec Soth, Keni. New Orleans (2018). © Alec Soth. Courtesy of Sean Kelly, New York.

Alec Soth, Galina. Odessa (2018). © Alec Soth. Courtesy of Sean Kelly, New York.

Alec Soth, Simone. Los Angeles (2017). © Alec Soth. Courtesy of Sean Kelly, New York.

Alec Soth, Yuko. Berlin (2018). © Alec Soth. Courtesy of Sean Kelly, New York.