Art World

Artcore: How the Pre-Raphaelites Were So Sick of Raphael

Contrary to what the name suggests, the Pre-Raphaelites came after the great Renaissance artist.

In 1854, at a time when divorce was considered taboo, Effie Gray went to court to annul her marriage to art critic John Ruskin. Gray cited the non-consummation of their wedding vows as justification for her separation, claiming her husband, a Victorian in the fullest sense of the word, had refused to touch her. A year later, she married painter and illustrator John Everett Millais, at whose side she remained until his death in 1896.

To art historians, Gray’s marriage to Millais reflects an important shift in British art. A founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, Millais had worked with Gray long before she became his wife. Between 1852 and 1853, she modeled for The Order of Release, a painting that sought to do away with the same stuffy values that defined Gray’s relationship with Ruskin.

How did the Pre-Raphaelites get started?

The Pre-Raphaelite movement began with the formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. Headed by Millais, William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, this group of painters, poets, and critics called themselves Pre-Raphaelites in opposition to the Royal Academy of London’s sustained obsession with the art of Raphael and his Renaissance compatriots.

Although the Pre-Raphaelites were rebels, they weren’t exactly revolutionaries. Instead of looking towards the future, inventing their own style from scratch in the vein of subsequent art movements, they took inspiration from art produced before Raphael, to medieval paintings made prior to—and, according to them, unfairly overshadowed by—the Renaissance.

So, the Pre-Raphaelites completely rejected Raphael?

Not exactly. Like the Raphaelites, the Pre-Raphaelites valued realism and technique—finely rendered details, true-to-life anatomy, and natural interplay of light and shadow. They also took inspiration from religion and classical mythology, at least at first. Ruskin, a leading figure in the art establishment of the day, was an ally rather than an enemy, encouraging Millais and his colleagues to experiment.

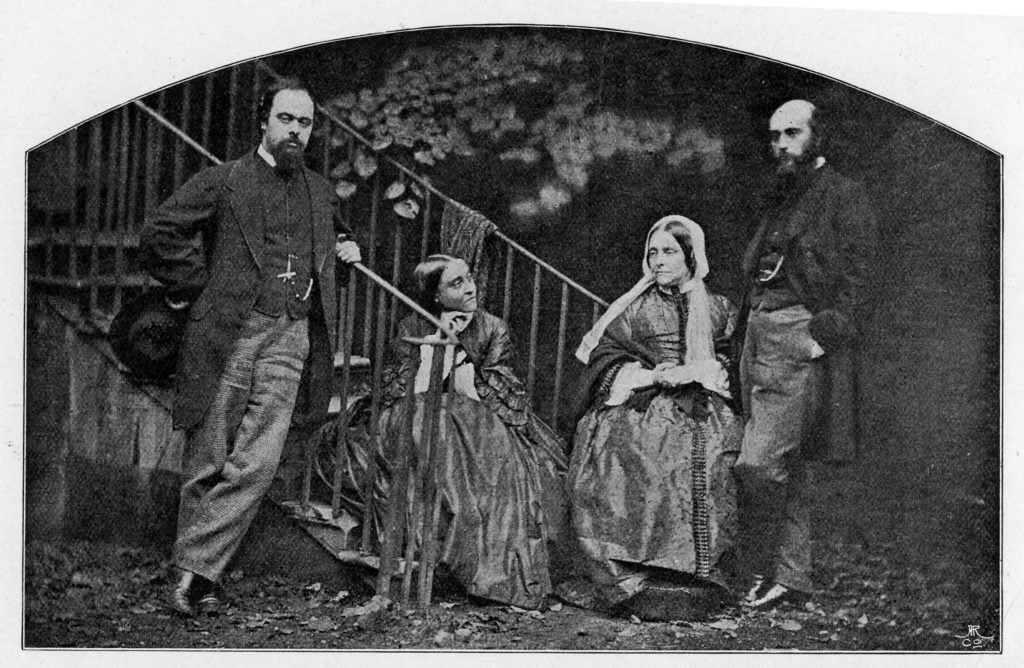

The Rossetti family, after a photograph taken by Lewis Carroll. From left to right: Dante Gabriel, Christina, Frances (mother, née Polidori) and William. Photo: Getty Images.

The real difference between the Raphaelites and the Pre-Raphaelites has nothing to do with how they painted but rather what they painted. If the Raphaelites favored idealized and, arguably, sterilized treatments of larger-than-life figures and events, the Pre-Raphaelites imbued their work with themes and emotions that didn’t often appear in Renaissance art, like love, sex, death, motherhood, and adultery. In short, the stuff that makes us human, flaws and all.

Like the Raphaelites, the Pre-Raphaelites enjoyed capturing the natural beauty of female subjects. Unlike the Raphaelites, however, they did not turn their models into stern, stoic, otherworldly Greco-Roman statues. Instead, they gave them agency and psychological depth, human characteristics that at times contrasted with their fantastical settings.

Sounds interesting. Any noteworthy examples of Pre-Raphaelite art?

John Everett Millais, Mariana (1851). Photo: Universal History Archive/Getty Images.

Aside from The Order of Release, Millais is best known for his 1851-1852 painting Ophelia, depicting a character from William Shakespeare’s Hamlet who, after learning that the titular prince murdered her father, throws herself into a river. Millais was not the first to portray Ophelia, but where previous painters depicted her post-death, the Pre-Raphaelite shows her in the midst of drowning, eyes open and palms raised: realistic, yet magical and sentimental.

John Everett Millais, Ophelia (1851–52). Photo: The Print Collector/Getty Images.

Millais’ depiction of Ophelia, based on 19-year-old model Elizabeth Siddal, reflects the rapidly changing gender norms of the late 19th century. Though seemingly dressed in time-appropriate garb, Ophelia is not wearing a corset, that ubiquitous symbol of Victorian squeamishness. Although the abundance of colorful plants and flowers floating around her only hints at her blossoming sexuality, critics were quick to denounce Millais’ imagination as “perverse.”

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Dante’s Dream (1871). Photo: Print Collector/Getty Images.

Also worth noting is Dante’s Dream by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. An adaptation of Dante Alighieri’s lesser-known work La Vita Nouva (“The New Life”), it depicts him being led into a dream by his eternal lover, Beatrice Portinari. Seeing the poetry of his namesake as an antidote to the industrialization and commercialization of his own day and age, Rossetti would return to Dante’s oeuvre throughout his career.

What happened to the Pre-Raphaelites?

James Collinson, Home Again (1856). Photo: Art UK via Wikimedia Commons.

Despite its success and influence, the Pre-Raphaelite movement was fairly short-lived. The Brotherhood disbanded in 1853, just five years following its creation. Weakened by the departure of prominent artists like James Collinson, who left because he felt the increasingly sensual art style was incompatible with his Catholic faith, and Thomas Woolner (who moved to Australia), the Brotherhood really fell apart when Millais joined the Royal Academy in 1853.

But while the Brotherhood disappeared, Pre-Raphaelite art endured. As Associate of the Royal Academy, the very institution he had rebelled against only a couple of years before, Millais was able to promote his previously rejected tastes, pulling British art institutions out of the Renaissance and propelling them into the 20th century.

Are the Pre-Raphaelites still relevant today?

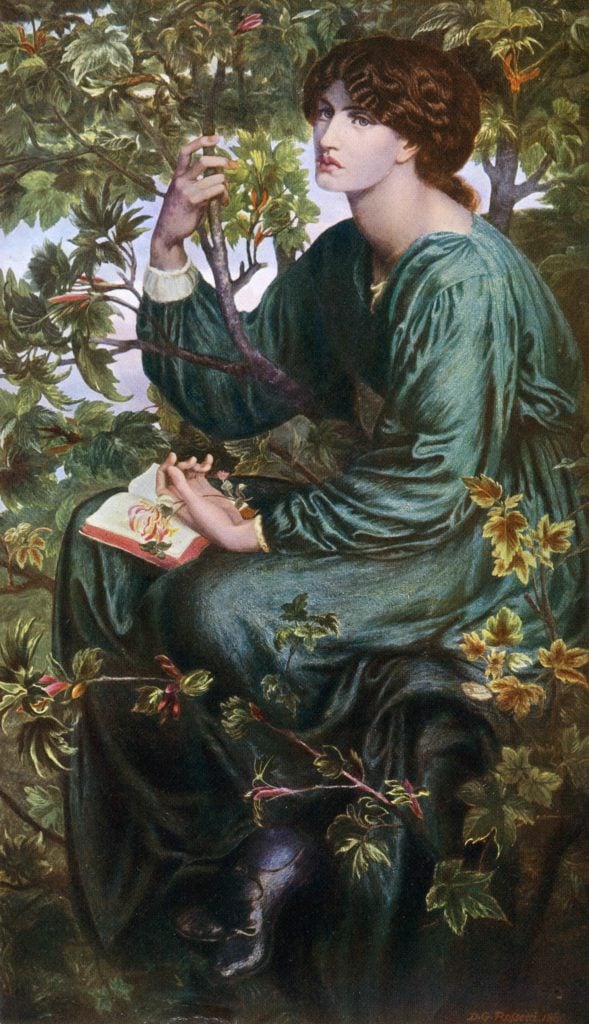

Dante Gabriel Rosetti, Day Dream (1880). Photo: The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images.

In addition to paving the way for 20th-century art currents such as the Aesthetics movement, Decadence movement, Arts and Crafts movement, and, by extension, the Vienna Secession, the Pre-Raphaelites should be remembered for providing serious pushback against Victorian-era sexuality and gender roles.

At the same time, it is worth noting, as Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore does in her review of a Pre-Raphaelite exhibition at the Tate written for the Guardian, that while “the Pre-Raphaelites challenged the gender norms for their day, new stereotypes arose out of the ashes of the old.” Rossetti’s work in particular lauded a particular form of beauty that not all women could or wished to attain: voluptuous, aloof, and—if not quite objectified—fetishized.

For as long as there has been art, revolutionary movements have continually reshaped its creation and perception. Artcore unpacks the trends that have shaken up today’s and yesterday’s art world—from the elegance of 18th-century Neoclassicism to the bold provocations of the 1990s Young British Artists.