The Hammer

Simon de Pury on the Superstitions That Fuel His Auction Victories

What do apples, crocodiles, and a lucky hammer have in common?

What do apples, crocodiles, and a lucky hammer have in common?

Simon de Pury

Every month in The Hammer, art-industry veteran Simon de Pury lifts the curtain on his life as the ultimate art-world insider, his brushes with celebrity, and his invaluable insight into the inner workings of the art market.

Unlike nearly any other part of the globe, Europe is a place that in August nearly shuts up completely. The only slowdown in the hectic calendar of the international art market happens during that month, with no public auctions of significance nor important art fairs taking place anywhere. The Germans refer to this season as das Sommerloch (the summer hole) and the Anglo-Saxons as the “silly season.” In less eventful summers than the current one the slowdown of news is compensated by sometimes frivolous stories gaining traction.

Over the last weeks talk in the industry was spreading like wildfire that a major work by Francis Bacon had been consigned for sale to Lévy Gorvy Dayan, the gallery with locations in New York, Hong Kong, and London. The fact that an important Bacon would have been consigned to one of the leading commercial art galleries is, in itself, not particularly newsworthy but the fact that it was going to be sold in a secret private auction was.

Jussi Pylkkanen. Image courtesy of Christie’s.

Lévy Gorvy Dayan asked Jussi Pylkkänen, who had been the hugely successful chief auctioneer at Christie’s and had recently left the firm after 38 years of loyal service to conduct the auction. All potential purchasers for the Bacon were discretely contacted. Those who did declare interest in bidding were asked to sign NDAs so that they could follow the auction that was scheduled on August 8. The choice of the date could not have been coincidental as August 8, 2024, translates in numerological terms to 8.8.8. Now, since the auction was meant to be secret and since I have no wish to antagonize any of the involved parties, I will not divulge how it went.

I admire the fact that both the consignor, who is a friend, and the seasoned professionals that are Dominique Lévy, Brett Gorvy, and Amalia Dayan were prepared to try novel approaches to the market. The choice of the date of that auction can only have been guided by superstition which prompts me to make my own contribution to the silly season.

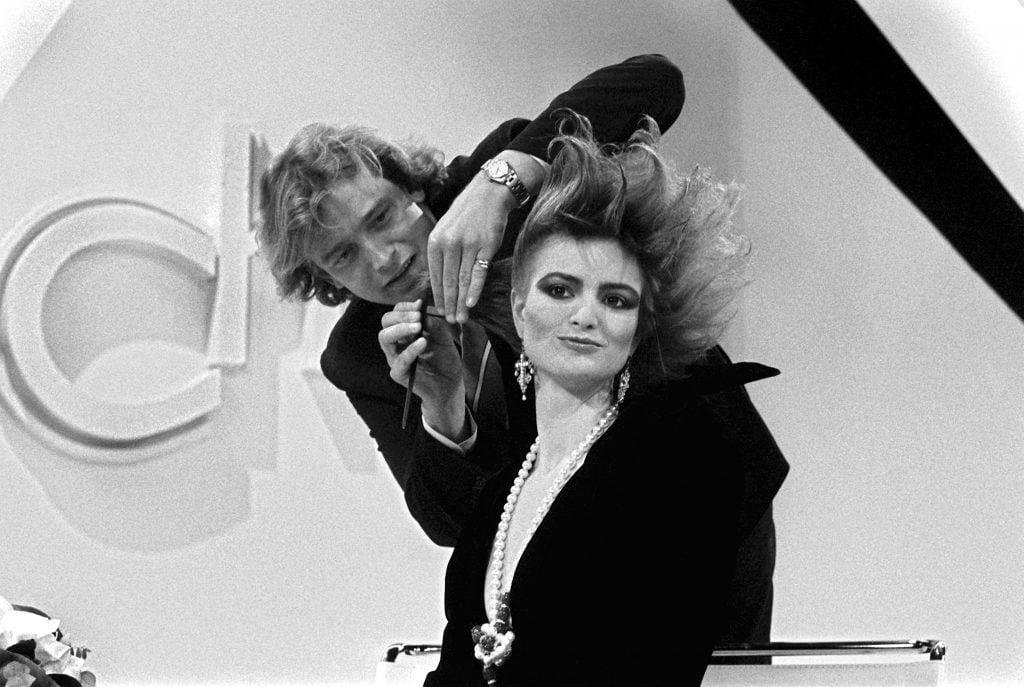

Celebrity hairdresser Gerhard Meir styles Princess Gloria von Thurn und Taxis’ hair into a modern punk hairstyle during the TV show “Chic” on January 22, 1986 in Studio Hamburg. Photo: Werner Baum/picture alliance via Getty Images.

I am personally extremely superstitious and collect superstitions. Every time I hear about a new one, I add it to my collection. This all started in 1993 when I acted as auctioneer for Sotheby’s of some of the contents of Saint Emmeram Castle in Regensburg, Germany belonging to the Princely Thurn und Taxis family during a five day auction. After the passing of her husband, Fürst Johannes von Thurn und Taxis, his widow Gloria, in those days being referred to as the “punk princess,” very smartly reorganized the family assets and transformed into gold the contents of the attics and cellars of the vast castle.

Every morning, walking through the castle on my way to the riding hall where the auctions were taking place, I would grab an apple from the big fruit bowls that were in nearly every room. The auctions turned out to be an unprecedented triumph. I figured out that this could only have been the case as a result of the sugar rush and boost of positive energy that eating the apples had provided me with. So much so that ever since I have to eat an apple before conducting any auction. In the rare cases I forget to do it, things simply will not work out as well.

(Original Caption) Woman holding her hand over a crystal ball and gazing into the future. Seated 1/2 length photograph. Photo: Bettman/ Getty Images.

One night after conducting the annual auction for Robert Wilson’s Watermill Center in the Hamptons, I was so elated about its outcome and so carried away by the electrifying music of a phenomenal DJ that I did not notice my auction gavel falling out of my pocket while I was dancing. By the time I realized that I had lost it, it was pitch dark so that I had to come back the next morning to look for it. I was devastated not to find it again, since it was my lucky hammer, with which I had knocked down works of art for hundreds of millions of dollars over the years.

I replaced it with a new one from a place in New York which supplies hammers to judges. To make the new hammer lucky I had to subject it to a ritual that I will not describe here, as it would certify me as being a total nut case. Meanwhile the new hammer has indeed become lucky and gained the necessary patina and aura. To make extra sure that an auction will be successful, I also have to wear the hammer cufflinks that my girlfriend gave me three years ago, and ideally have a tiny plastic crocodile in my pocket that my youngest daughter gave me as talisman.

Medium Eusapia Palladino (woman in the background) during mandolin levitatation during a seance at the house of Baron von Schrenck Notzing in Germany march 13, 1903 Photo: Apic/Getty Images.

Superstition alone is not sufficient. The positioning of the stars and the planets, numerology and clairvoyance are all things that fascinate me. Some 25 years ago I was introduced by an Indian princess to an extraordinary clairvoyant. Everything she told me turned out to be true. So much so that I began to call her more and more frequently with endless questions, until I realized that I had developed a dependency. As with any addiction, the only way to halt it is to cut it completely, which I did.

I remember once walking through an auction preview exhibition with her. While she had zero knowledge of art and of the art market she would point to a painting and say “this one will fly,” then look at a sculpture and say “this one will be tough,” and about a third work, “you will sell it but at the low end of the estimate.”

As with everything else, once you dig a bit you realize you are by no means alone. George Ortiz, one of the greatest collectors of antiquities and tribal art ever, had told me one day that 13, a number that is often being shunned by superstitious people, was his lucky number. For years I was coveting a stunning silver tureen made by Thomas Germain, the sculptor-goldsmith to Louis XV, that George Ortiz had inherited.

Penthievre-Orleans Service. A Louis XV royal silver tureen, cover, liner and stand, Thomas Germain, Paris, 1733-3, Sotheby’s New York, Royal French Silver: The Property of George Ortiz, November 13th, 1996. Courtesy Sotheby’s.

I had helped George Ortiz bring about an exchange between parts of his collection that was exhibited at the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, and a choice of objects that George Ortiz had selected in Soviet museums and exhibited at the Kunsthaus in Zurich. To thank me, he had promised that should he ever sell the tureen he would do so at Sotheby’s. When I heard that the 1996 fall New York silver auction was scheduled to take place on November 13, I called George and told him that the stars were aligned, and that he therefore should consign his tureen. If he did so, we would sell it as lot 13. This convinced him.

Luckily, the stars were indeed aligned and the tureen sold for $10.3 million, pulverizing the previous world record for a silver object. George’s older brother Jaime Ortiz-Patiño, with whom he was not on the best terms, had in 1989 consigned through me a formidable collection of Impressionist paintings to Sotheby’s in New York. He followed the proceedings from one of the skyboxes overlooking the sale room. When I went to congratulate him for the outstanding results, he proudly showed me the cufflinks of frogs that he was wearing, and said that they were the reason why the sale had done so well.

The art world and its market are a tiny microcosm. Being part of it cannot make you ignore the world at large. Even for the incurable optimist that I am, the dark clouds accumulating on the sky these days are visible. In these uncertain times we can only hope that the stars will eventually realign.

Simon de Pury is the founder of de PURY, former chairman and chief auctioneer of Phillips de Pury & Company, former Europe chairman and chief auctioneer of Sotheby’s, and former curator of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection. He is an auctioneer, curator, private dealer, art advisor, photographer, and DJ. Instagram: @simondepury.