Art World

Those Pink Hats at the Women’s March Can Teach Us Something About Political Art

The vast sea of pink knit hats was almost poetically beautiful.

The vast sea of pink knit hats was almost poetically beautiful.

Ben Davis

Donald Trump’s inauguration was the smallest in recent memory. That’s the truth, whatever the patter about “alternative facts.” Saturday’s Women’s March on Washington, on the other hand, may have been the largest single coordinated protest in US history, a landmark day.

Trump is officially Commander-in-Chief now, and he will do what he has committed to do: desecrating Native American lands by enabling the Dakota Access Pipeline; making good on his lunatic pledge to build a Mexican border wall; banning Muslim refugees.

But he will face resistance. The protests showed that, beyond a doubt.

I went to the protests in Washington, DC, both on Friday and Saturday. In the bleak dawn hours before the inauguration, Trump supporters and protesters pressed through the checkpoints to reach the fenced-in areas around the motorcade route, closely packed together, eyeing each other uneasily.

It was clear already that the symbolism of the inauguration would be contested—but by how much? What was the relative weight of the forces?

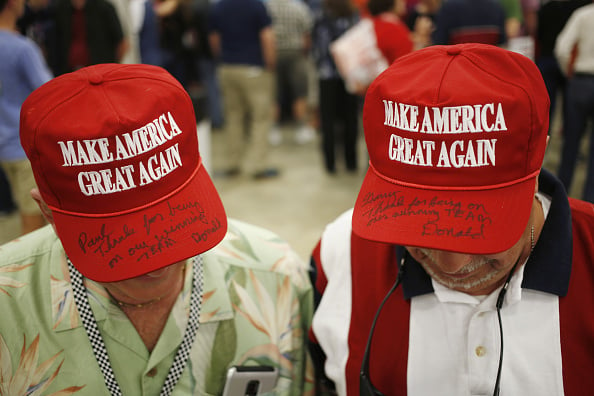

The protesters weren’t exactly clearly marked out. The Trump fans were: Anything with an American flag, all those “Bikers for Trump” in their leather jackets, and above all, anyone wearing a red ball cap with the screaming, all-caps “MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN.”

The MAGA ball cap was the Shepard Fairey Hope poster of 2016, the symbol that condensed a campaign’s tone and appeal for its adherents. The hat was not an example of “good design;” just the contrary, in fact, with Fast Company declaring it the “worst” but also “most-effective” design of 2016.

Attendees wear hats in support of Donald Trump. Photo by Luke Sharrett/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

The article quotes Michael Moore, one of the few who predicted the Rust Belt momentum that carried Trump to the White House, dissecting the symbolism of the MAGA cap to Morning Joe:

I take no pleasure in calling this [election] five months ago. Someone [on this show] was remarking that the Trump campaign spent more money on ball caps that month than anything else. And you panelists were [laughing] ‘ha ha ha ball caps.’ I looked at that and thought, ‘Wow there’s the bubble right there.’ They don’t understand. This is where we’re from. This is where I live. And to make fun of [people wearing the hats]? . . . This is the reason [Middle America] had this anger at the media and this elitist thing.

For something that has become such an all-present symbol, the Trump hat’s exact origin remains sort of a mystery. Its success may be more than accidental, a self-consciously unrefined fashion statement—but it was at least partly accidental, which tends to be the way things go with truly resounding political symbols.

What gives them their charge is grassroots cachet. They therefore tend to come from unexpected places, to be slightly odd at first glance.

Shepard Fairey’s Hope poster has become so iconic that we forget that its origin was unauthorized, its street-art roots touching an untapped youth-culture nerve. The symbol of Pepe the Frog insinuated itself into public consciousness in a similar way, as Trump tapped into the nastiest depths of internet troll culture.

Clinton never inspired any similar symbolic breakthrough (right at the buzzer, the pantsuit began to take off as a symbol of the feminist enthusiasm for her campaign—but too late to be more than a footnote). Her campaign got by on a slick “design system” put together by the firm Pentagram, polished but inspiring little passion, the expression of a campaign that played it safe.

A group of demonstrators play drums during the Women’s March on Washington January 21, 2017 in Washington, DC. Photo by Zach Gibson/AFP/Getty Images.

Which brings me to the Women’s March, and its unexpected but unmistakable totem: the so-called “Pussyhat” (rhymes with “pussycat”).

At Saturday’s supermarch, the sight of a vast sea of pink knit hats seemed almost magical. They were everywhere—hundreds of thousands of handmade caps, flooding the National Mall as far as the eye could see. They were immediately recognized as a natural rejoinder to Trump’s MAGA cap.

The teeming symbolic gesture sprang from the thwarted hopes for a first female president—though it may also be worth noting that its urgently claimed, brazenly feminist statement was only possible outside of the symbolism of Clinton herself. Sexism meant that she had to keep any imagery deemed too feminine at arm’s length, while her campaign strategy fixated on peeling off centrist Republicans alienated by Trump. Both are hard facts.

Thousands of activists from across the United States and abroad gather on Independence Avenue for a rally proceeding the ‘Women’s March’ in Washington, DC on the day following the inauguration of President Donald Trump. Photo by Albin Lohr-Jones/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images.

The Pussyhat began as a post-election art project. The widely shared design came courtesy Kay Coyle, the master-knitter owner of the Little Knittery in Los Angeles: a simple pink rectangle, the corners of which perked up into cat-like ears when worn.

Like most truly resonant symbols, it packs a lot into a simple thing. The Pussyhat was elegantly simple, the better to be shared widely; it was obvious in its hot-pink symbolism, the better to serve as a statement; it was witty and unexpected, the better to attract genuine enthusiasm; it was a little outrageous—“Pussyhat” self-consciously claiming the vulgarity associated with Trump’s infamous leaked Access Hollywood tape—the better to represent a bit of the defiance of the moment.

Ann Mitchell, just hands shown, puts the finishing touches on a pussyhat as, from left to right in the back Jen Grant, Julie Piller, and Debbie Asmus all help to knit dozens of pink hats at the home of Jen Grant on January 15, 2017 in Lafayette, Colorado. Photo by Helen H. Richardson/The Denver Post via Getty Images.

It also stands deliberately in a long tradition of feminist art reclaiming women’s traditional crafts as a political statement. Reports from around the country had knitting centers turning into protest hat-making hubs in the lead-up to the Women’s March. Those who could not go for whatever reason (disability, lack of economic means, fear of crowds, fear of the police or of Trump supporters) made hats and sent them with notes of solidarity for those who could.

Marchers attending the Women’s March on Washington hold up women’s rights signs critical of President Donald Trump on January 21, 2017 in Washington, DC. President Trump was sworn in as the country’s 45th President the day before. Photo by Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images.

The Pussyhat initiative did not go without controversy. Writing in the Washington Post in the lead-up to the March, Petula Dvorak saw the hats as an example of participants caving into “the temptation to make the protest fun, enjoyable, to give it a street-fair feeling and draw more people.” She viewed all this as a distraction from the hard business of protest:

[W]e can’t make a difference with goofy hats, cheeky signs and silly songs. This is our chance to stand up, to remind the world how powerful we are and demand to be heard. On equal pay and opportunity, on sexual assault, on reproductive rights, on respect. We need to be remembered for our passion and purpose, not our pink pussycat hats.

I’m all for clear messaging. It’s true that on the ground, the march was pretty woolly (pun intended) in terms of what it represented. The truly righteous messages were mixed in with those ranging from the vague (“Love Trumps Hate”) to the inscrutable (“Pizza Rolls Not Gender Roles”).

But is it helpful to set up an opposition between artistic action that, Dvorak seems to admit, “draws in more people” and the hard work of consolidating a “serious message?” With whom are you consolidating that serious message with if not with the people who are drawn in by the more abstract and poetic one?

Here is Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, replying to a wave of lefter-than-thou online commentary charging the Women’s March with not being radical enough:

The scale of the attack [from the Trump administration] is as deep as it is wide, and this means that we will need a mass movement to confront it. To organize such a movement necessarily means that it will involve the previously uninitiated—those who are new to activism and organizing. We have to welcome those people and stop the arrogant and moralistic chastising of anyone who is not as “woke”.

Just so.

It’s only a few days into the Trump presidency, and you can see that it’s going to be a horror show. With so many blows raining down, keeping an even keel is not going to be easy. Every action is going to be open to the charge that it is somehow inauthentic, unreal, beside the point, merely symbolic.

The danger of this mindset is that it enforces atomization and isolation, that you become blind to the symbols that new people are using to find each other, which by definition come from new places. Critique can easily become its own bubble, as removed from the symbolism that actually moves people’s lives as those commentators on Morning Joe: “ha ha ha pink hats,” instead of “ha ha ha ball caps.”

“We don’t know the effects of what we put out there. If we knew, then we’d only do the things that had an effect,” one of the Pussyhat Project’s co-creators, Jayra Zweimal, said. “But I think that we’re seeing the effect in the process of making these hats.”

If you are waiting around for a political symbol that has any kind of mass resonance but that is also completely under your control, you are going to be waiting for a long, long time—long enough for a giant parade of red-hatted men to stampede all over you.

Protesters fill Pennsylvania Avenue during a rally at the Women’s March on Washington, Jan. 21, 2017. Photo by Jessica Rinaldi/The Boston Globe via Getty Images.

Maybe the Pussyhat is not your thing. Maybe it’s too wacky or too cutesy, not “nasty” enough or too nasty, too pink, whatever. I don’t know what larger afterlife it will actually have as a symbol beyond Saturday.

What I know is that at the Woman’s March on Washington, it represented the kind of spirit that I think is needed: the will to create a statement that is too visible to ignore, and to provide the warmth to get people out together in an inhospitable climate.