Art & Exhibitions

Rare 17th-Century Painting of Black and White Women Debuts After Export Ban

The highly unusual painting reveals 17th-century anxieties over immorality, vanity, and foreign influence.

The highly unusual painting reveals 17th-century anxieties over immorality, vanity, and foreign influence.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

An exceptionally rare 17th-century painting featuring a Black woman and a white woman side by side has gone on public display for the first time at Compton Verney, a historic manor in the English county of Warwickshire. The work is freshly cleaned following an 18-month conservation and research project, which revealed new information about how it reflects the cultural anxieties of its time, as well as deeply embedded racist and misogynistic beliefs.

“It’s an incredibly complicated and troubling painting,” said Jane Simpkiss, the display’s curator, during a walkthrough of the show, on display in the women’s library. “But it’s also unique in British art and allows us to widen our understanding of how people in the 17th century understood issues that are still important today.”

The allegorical painting, Two Women Wearing Cosmetic Patches, was made in around 1655, most likely for Roger Kenyon, a local politician from Lancashire, in northern England. It is not known why it was commissioned. The two women face each other in sumptuous dress and have their faces adorned with cosmetic patches. The Black woman wears white patches while the white woman wears black ones and appears heavily made up, with her cheeks and lips rouged and her skin likely whitened by ceruse.

Cosmetic patches were used to cover up facial scars and blemishes, perhaps from smallpox or venereal diseases. Often made of silk, satin, or leather, these patches were cut into shapes and applied using animal glue.

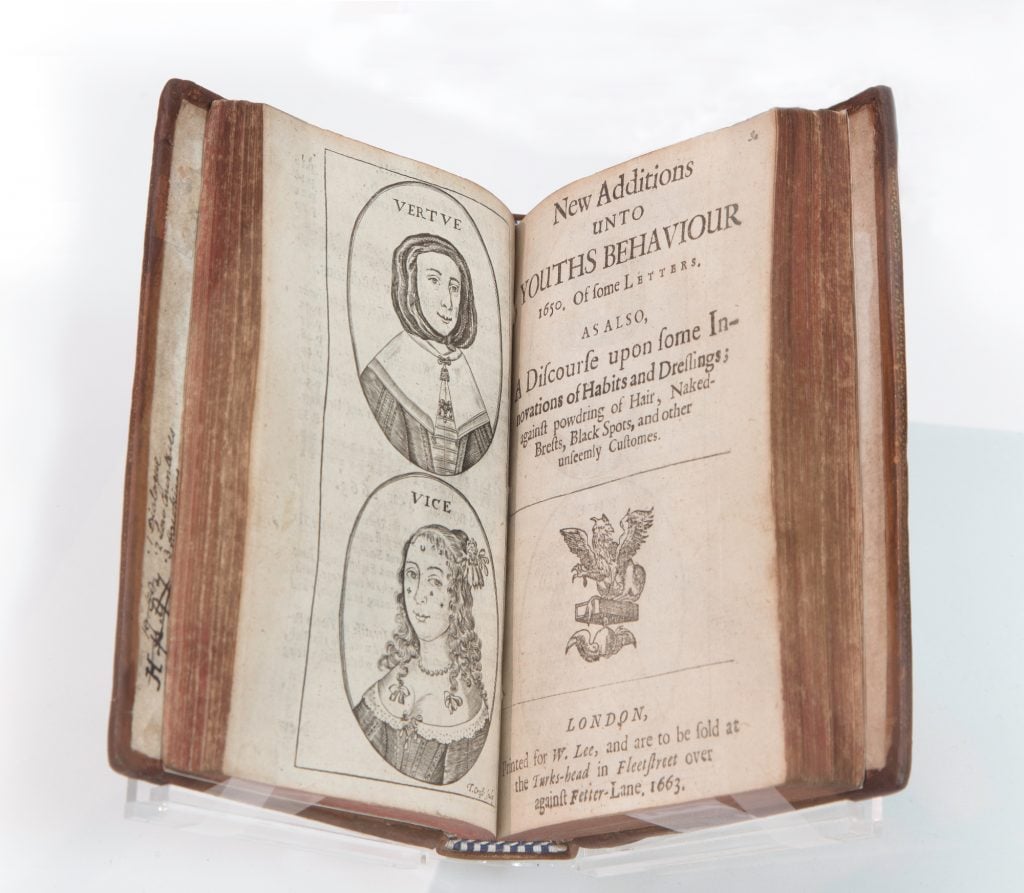

Francis Hawkins, Youths Behaviour, or Decency in Conversation Among Men (1663). Photo: Jamie Woodley, © Compton Verney.

The scolding, moralistic tone of the painting is established by the inscription above the women’s heads. It reads: “I black with white bespott: yu white wth blacke this Evill: proceeds from thy proud hart: then take her: Devill.” This strongly worded chastisement describes the use of cosmetic patches as an exercise of pride that will condemn the sinner to hell.

Although the use of cosmetic patches is a practice dating back to ancient times, mid-17th-century England was experiencing a moral panic over excessive female vanity. In 1649, parliament considered but eventually rejected a proposed ban of “the vice of painting and wearing black patches, and immodest dress of women.”

The display at Compton Verney includes two books that provide some context for the painting. One, published in 1663, is Francis Hawkins’s translation of a French conduct guide titled Youths Behaviour, or Decency in Conversation Among Men, which described the use of patches as an “unseemly” custom. It labels a very modestly dressed woman as virtuous while a woman in fashionable but revealing dress and styled hair wearing patches is labelled as “vice.”

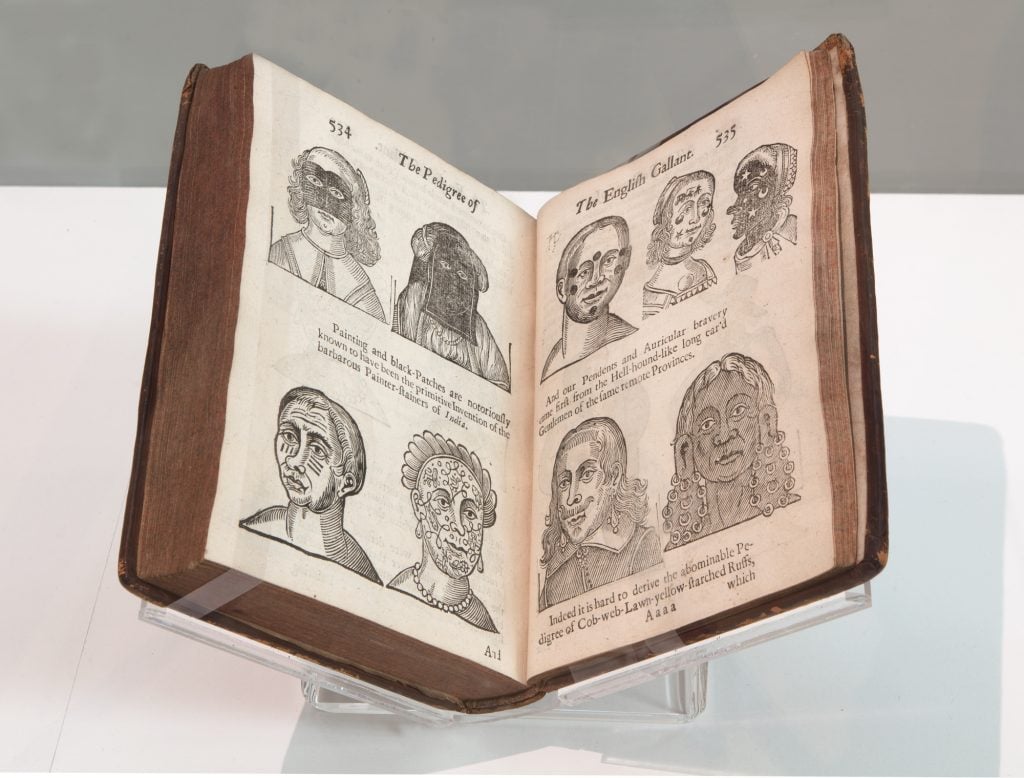

Most notably, a very similar image to that in the portrait, again showing a white and a Black woman facing towards each other, appears on page 535 of John Bulwer’s Anthrometamorphosis: the man transform’d or, the artificiall changeling (1653), in which the author characterizes body art as a disfigurement of God’s creation. Opposite the painting’s possible source image, a text reads: “Painting and black-Patches are notoriously known to have been the primitive Invention of the barbarous Painter-stainers of India.”

John Bulwer, Anthrometamorphosis: the man transform’d or, the artificiall changeling (1653). Photo: Jamie Woodley, © Compton Verney.

These anxieties over perceived immorality and foreign influence erupted during a period of radical political and social upheaval in Britain following civil war, the execution of King Charles I in 1649, and Oliver Cromwell’s subsequent rise to power. The painting offers an insight into how those in power “tried to retain a sense of certainty and stability in an incredibly unstable time,” according to Simpkiss.

Initial contemporary readings of Two Women Wearing Cosmetic Patches had interpreted the two women as being of equal status, which would have been highly unusual since most English 17th-century portraits featured Black sitters only in the role of attendants. However, in reality, “the Black woman is supposed to amplify the sins and misdeeds of the white sitter by suggesting that not only are her uses of cosmetic patches vain but also undermining of her English identity by aligning her with the customs of other, non-European nations,” explained Simpkiss.

The unusual painting remained in the Kenyon family until 2021, when it was bought at auction by an overseas buyer. Due to its rarity and significance, the painting was placed under a temporary export bar in 2021, buying time for a U.K. institution to acquire the work for £300,000 ($380,000) and save it for the British public.

Compton Verney is an elegant 18th-century mansion housing a public art gallery with collections of Neapolitan art, Northern European medieval art, British portraiture, and British folk art. It also has a program of temporary exhibitions of historical and contemporary art.