Pop Culture

Meet the Real Lempicka: A New Documentary Reveals the Art Deco Star’s Untold Origins

The film includes contributions from Anjelica Huston, Eden Espinosa, and Lempicka's heirs.

This year has been Tamara de Lempicka’s year—and it’s far from over. Two thousand and twenty-five will see the New York debut of the new documentary, The True Story of Tamara de Lempicka & the Art of Survival, at the 34th Jewish Film Festival.

Rather than focusing on fast women and fashionable parties, director Julie Rubio’s film, five years in the making, shares the harrowing realities behind Lempicka’s glamor magic. It marks the first feature film dedicated to the world’s third-most expensive female artist.

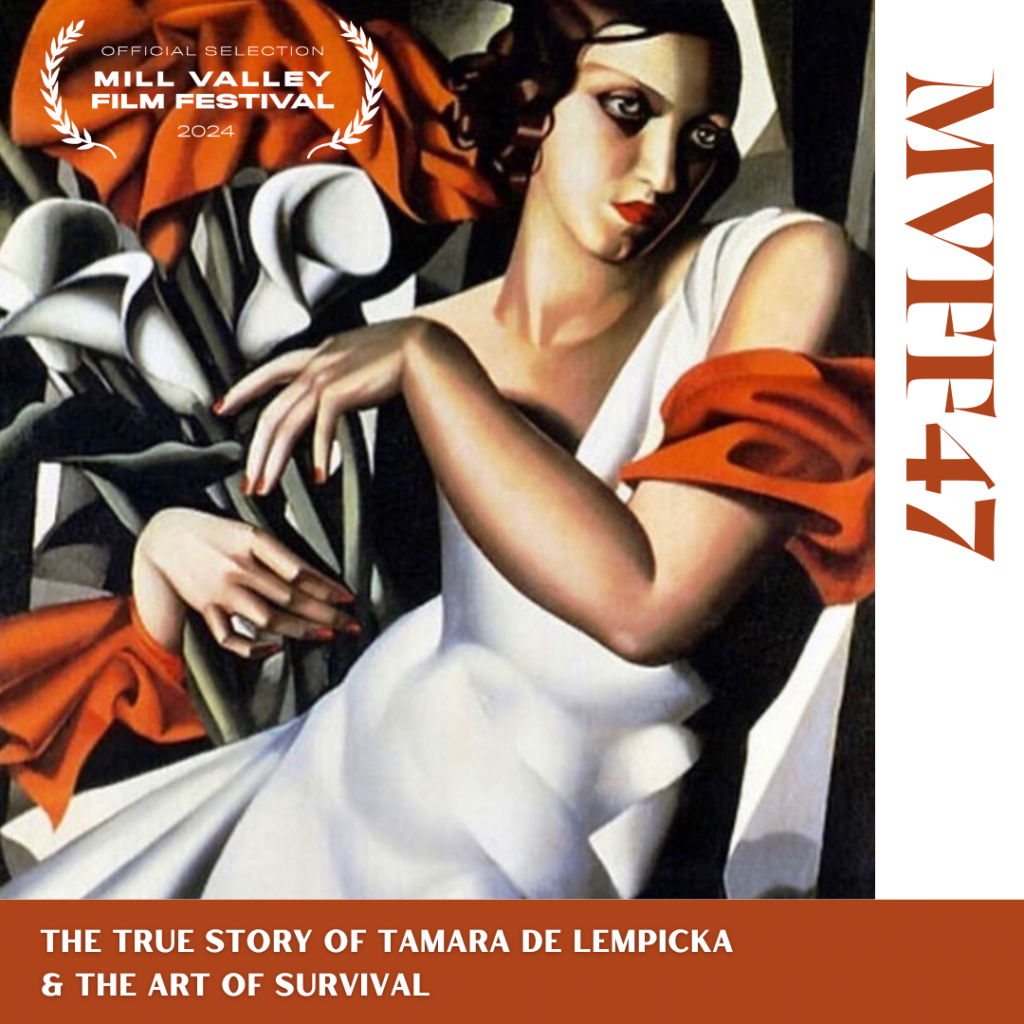

A flyer for the film’s Mill Valley Film Festival appearance, featuring Lempicka’s Portrait of Ira P. (1930). Photo: East Meets West Productions LLC.

The True Story of Tamara de Lempicka first screened at the Mill Valley Film Festival in September. An eclectic crew outlines Lempicka’s life through the lens of her artworks, accompanied by animation, archival photos, and never-before-seen home video. Lempicka’s granddaughter and great granddaughters anchor the documentary, while art dealers and historians offer outside expertise. Eden Espinosa, who played Lempicka on Broadway, appears, as does the musical’s composer Matt Gould.

Overall, the film extends beyond Lempicka’s Parisian heyday into her Hollywood era, and the ennui of her later years when she flirted with movements as an American artist. Anjelica Huston—who played Lempicka in the L.A. production of Tamara in the 1980s—offers narration along the way.

Rubio first learned of de Lempicka 30 years ago, while visiting Miami. “I found myself in this hotel called the Americana,” she recalled over the phone. They were showing Lempicka prints. “Her art really spoke to me.” That day, a friend told Rubio that Lempicka had been bisexual. Rubio, who’d had girlfriends, had never even heard the term.

Director Julie Rubio and Co-Producer/DP Svetlana Cvetko stand by Lempicka’s L’eclat (1932). Photo: East Meets West Productions LLC.

The filmmaker continued learning more about Lempicka. Then, 20 years ago, one of Rubio’s friends introduced her to the living Lempickas during an opening at Manhattan’s Weinstein Gallery. They were actually looking for a woman, specifically, to write a narrative screenplay about Lempicka. Rubio listened to stories, drafted several scripts, and set about securing funding.

That money never came, even after Rubio shifted to a documentary model in 2020. Two people close to Lempicka’s life even asked Rubio to pay them for appearances. She declined. Those involved donated millions of dollars “in kind” to make The True Story of Tamara de Lempicka happen, the director said. Huston, for instance, proved hard to reach—until Marisa de Lempicka unearthed a letter in which Huston declined a request from Lempicka’s daughter Kizette to star in a movie about the artist.

Rubio and art dealer Rowland Weinstein, who also appears in the film. Photo: East Meets West Productions LLC.

“I sent Angelica that letter, and I said, ‘Look, Kizette was trying to get the story done 40 years ago or more, and here I am trying to get this story done,'” Rubio recalled. After that, Huston came on board.

Streisand, a noted Lempicka aficionado who sold Adam and Eve (1932) for a record-breaking $1.98 million in 1994, was too busy penning her memoir to work directly with Rubio. But, Streisand’s team did coordinate high resolution images from her expansive collection—with advice on how to use them straight from the star herself. (Rubio then connected Streisand with the de Young, which is currently staging a Lempicka retrospective; the singer wrote the preface to its exhibition’s catalog.)

Lempicka painting her departed husband Tadeusz in 1929, eleven years after they fled Russia for Paris together. Photo: East Meets West Productions LLC.

The True Story of Tamara de Lempicka also publicizes recently-surfaced documents which allude that Lempicka’s known affinity for obscuring her origins was not an act of vanity or even entrepreneurship—but one of survival.

The artist’s birth certificate remains missing. But, for her film, Rubio commissioned original footage documenting the graves of Lempicka’s maternal grandparents at a Jewish cemetery in Warsaw. Lempicka’s loved ones had never known the precise cemetery for themselves.

Rubio then traded that footage with Polish journalist Monika Krawjewska, who unearthed the last surviving documents evidencing Lempicka’s grandparents’ conversion to Christianity. In the film, Krawjewska notes many such conversions were forced. She also points out that Lempicka was smart to obscure her Jewish heritage after fleeing to Paris from the Bolsheviks, since European antisemitism was reaching a fever pitch.

“She was painting her daughter and her First Communion,” Rubio told me, referring Lempicka’s Kizette Communiante (1928). “Her daughter never had a first communion.”

Tamara de Lempicka with Miss Cecelia Myers, 1940. Photo: ACME Photo Collection of Richard and Anne Paddy, USA.

The documentary also cites a newly surfaced baptism certificate from 1897 which confirms that Lempicka’s original name was Tamara Rosa Hurwitz—and that she was born in 1894, not 1898. At first, Lempicka’s family resisted including these developments, Rubio told me. The director insisted on their importance.

“Tamara’s story shows us how to survive and navigate really horrific things,” Rubio said, adding that she lost her mother and best friend while making this film. “I realized so many people go through so much. Here’s this woman that lost her country twice through war. She just kept figuring out how to find the beauty in life.”

Even after a banner year like 2024, critics still struggle to take Lempicka seriously. Rubio and her collaborators believe in the substance beneath Lempicka’s style.