Art World

The Remarkable True Story of Raúl Giansante, Uber Driver, Master Frame-Maker, Comrade of Dalí, and Zelig of the Art World

The NYT interviewed him in his taxi about New York's shutdown. He has many other stories to tell.

The NYT interviewed him in his taxi about New York's shutdown. He has many other stories to tell.

Ben Davis

I first came upon Raúl Giansante as one of the faces of the crisis—or, rather, one of the voices. One month ago, the New York Times’s Daily podcast presented interviews with New Yorkers on the eve of the city’s lockdown. Raúl, gently affable, was interviewed in the car that he was then still driving for Uber.

Why was he still working when the city was shutting down, the reporter asked? “Because to tell you the truth, because the retirement in the United States is so low that it’s not enough to buy food,” he explained. “So I have to work.”

On the podcast, Raúl mentioned in passing that he had previously worked in making hand-carved frames for artists. The reference stuck in my head, and I found a website featuring his work. I also found that he had a much more interesting backstory than anything I could have imagined.

I decided to call him up. And, having talked to him, I decided to tell you his story.

In 1969, at the age of 21, Raúl Giansante fled his native Argentina, which was then wracked with violence in the fallout from a rightwing coup d’etat. He already identified as an artist, and the climate was increasingly fraught. So he headed to Mexico City, where he lived in a collective house for intellectuals. An attached woodworking shop let him hone his skills with carving.

The house drew Mexico’s artists. One, the famous painter Rufino Tamayo, would set Raúl on what would be his lifelong path. Visiting the house, he glimpsed the young Argentine carving a sculpture of Don Quixote, and asked him to make a hand-carved frame for him. Mexico’s art schools then were still rooted in Spanish arts and crafts style, and Tamayo was looking for a different look.

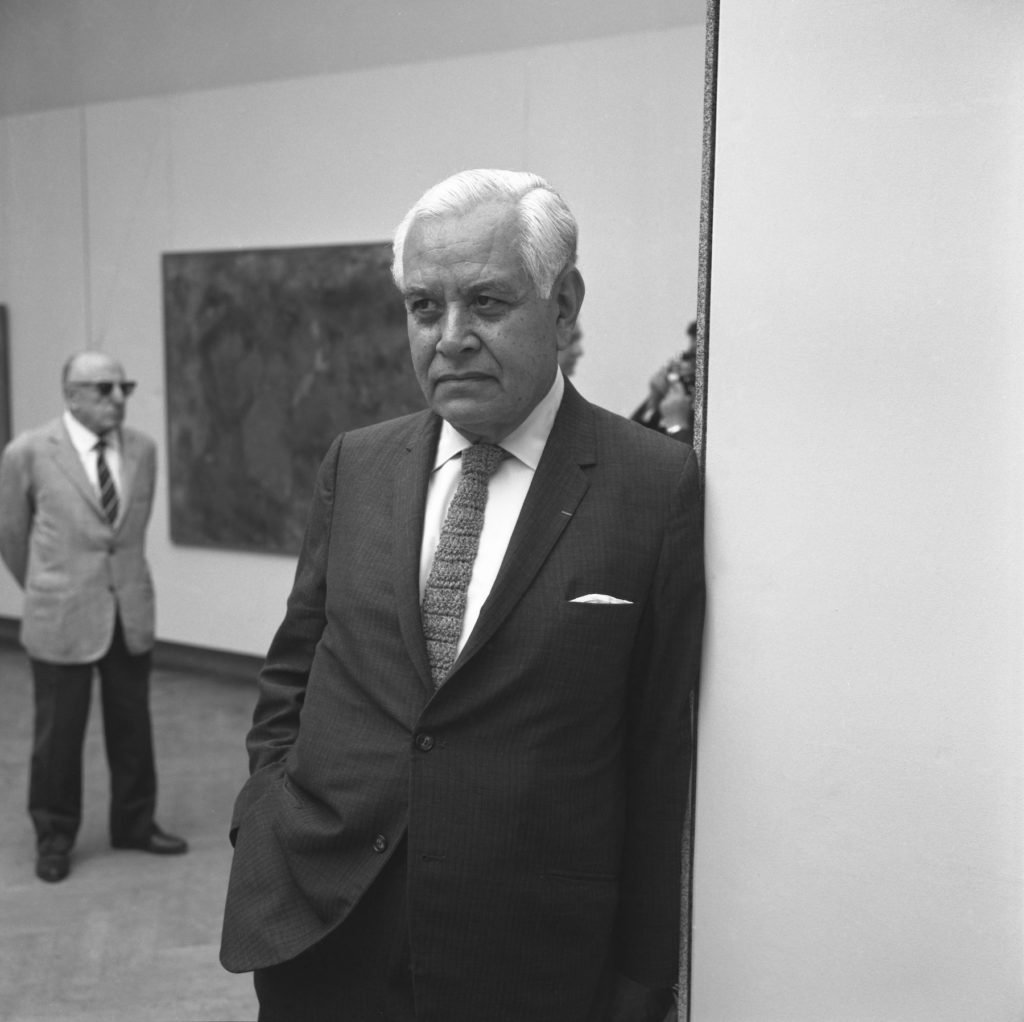

Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo at the Venice Biennale, 1968, shortly before the time he met Raúl Giansante. Photo by Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche/Getty Images.

“I told him, ‘I don’t know what I can do for you,’” Raúl remembered. “’You are the master. I’m just a regular carver.’” Tamayo insisted, even taking the young artist to a carpenter to learn how to construct a profile for a frame.

It took a month to make those first two frames, Raúl remembers. Tamayo liked the results, and asked him to create more handmade frames for his paintings going forward. “He was the one who invited me into this world.”

Through Tamayo, Raúl was introduced to other artists working in Mexico, including the Costa Rican painter Francisco Zúñiga. But his most important encounter came when the flamboyant Spanish surrealist Salvador Dalí, then in the late bloom of his international celebrity period, sought him out at the house, bringing two wrecked Louis XV frames he hoped to use in a show at the Palacio de Bellas Artes. Raúl, of course, had no idea how to fix the antiques, so Dalí asked if he could fabricate new ones instead.

“That was a Monday,” Raúl says. “I asked him when he needed them. He said, well, I need them Friday because Saturday is the opening day of the show. I spent five days almost not sleeping to get them done.”

Dalí was impressed with the young woodworker’s hustle. “He said to me, ‘You know, in Spain they take about three months to make two frames and they do it wrong. But you, in five days, have made me this beauty.’ He said, ‘Come with me to Spain—I need you.’”

Raúl was 23 years old at the time. He couldn’t pass up on the opportunity.

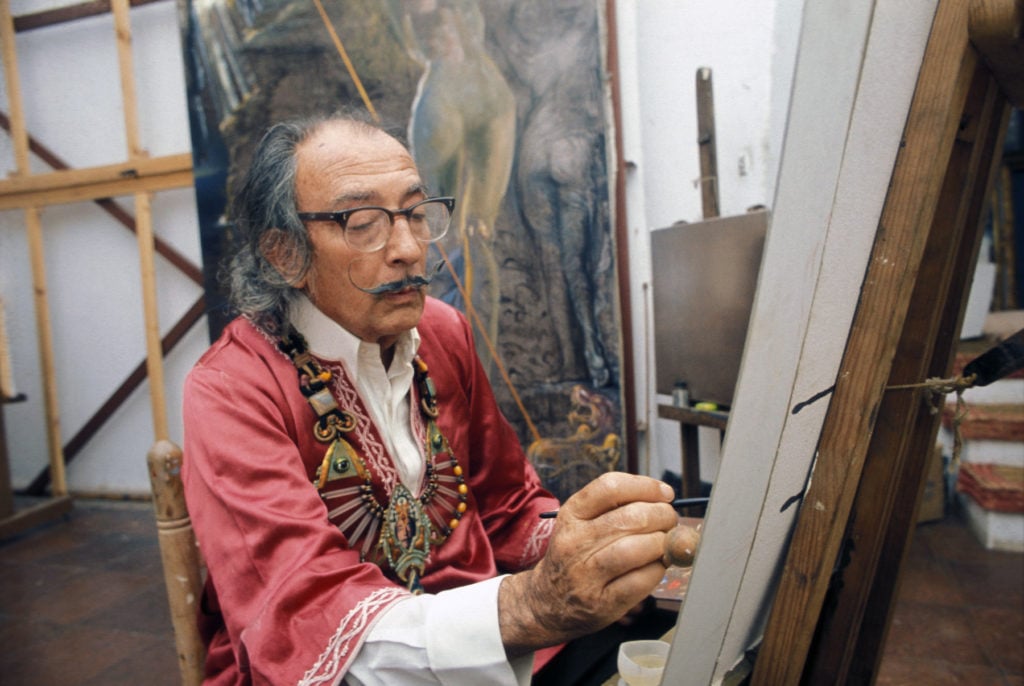

Salvador Dalí painting in his studio in Spain, circa 1970. Photo by Etienne Montes/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

For the next decade, until Dalí passed away from Parkinson’s in 1981, Raúl worked with the Spanish painter. Well-known artists came often to Dalí’s studio in Cadaques, and the artist brought them also to visit Raúl’s nearby workshop, opening a world of further associations. His hand-carved frames came to adorn the work of the likes of Joan Miró and Francis Bacon.

Dalí’s globetrotting lifestyle saw him spend six months in Spain and six months in New York each year. Eventually, Raúl was running workshops in both the US and Europe, and would at last come to live permanently in the States.

Raúl’s business grew with the consolidation of New York’s downtown scene, which would yield SoHo’s so-called “decade of decadence” in the 1980s. Through his work with Francis Bacon and Rufino Tamayo, he was introduced to Marlborough Gallery, where he served as the official framer until the start of the new millennium.

He also did framing for the legendary gallerist Leo Castelli. For six years, he did bits of work for Andy Warhol. He was close with the Op artist Victor Vasarely, who ran his own dedicated showroom, the Vasarely Center, on Madison Avenue. He knew well Tony Rosenthal, creator of Astor Place’s beloved black cube sculpture, and worked with film star-turned-painter Anthony Quinn.

At his peak, Raúl’s workshop in Brooklyn occupied 16,000 square feet on the corner of Third Avenue and Third Street, essentially a factory, employing 75 people. “We were framing for about 50 to 60 galleries in New York, Chicago, all over.”

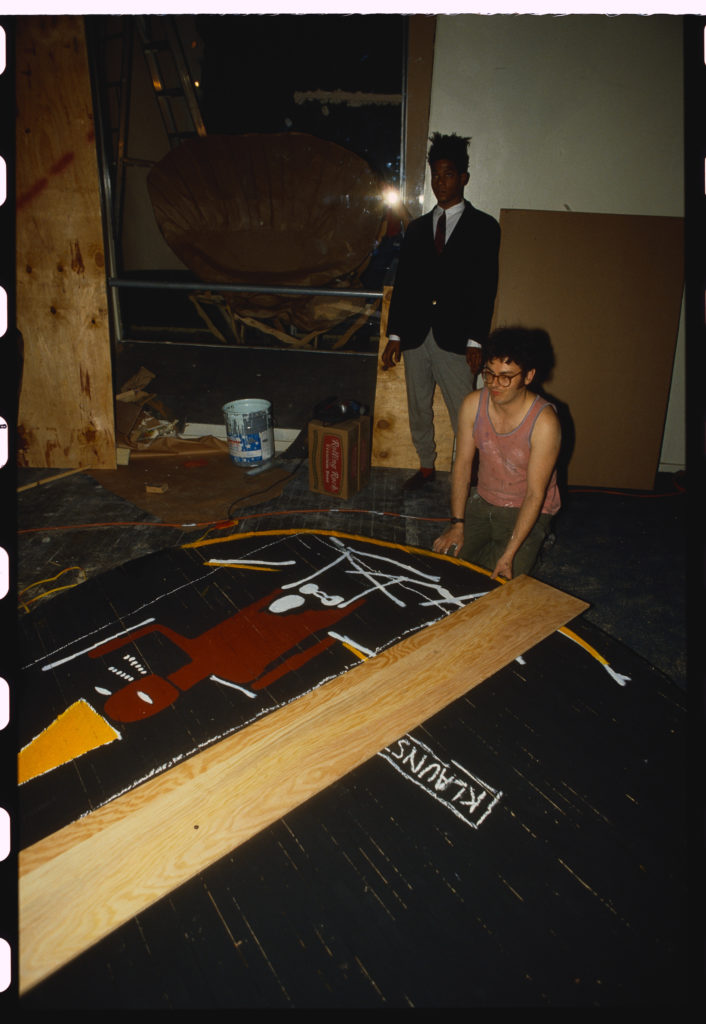

Jean-Michel Basquiat looks on as one of his artworks is inspected at Area, a Manhattan nightclub, in January 1980. Photo by Nick Elgar/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images.

It was in the Brooklyn studio that he met the young Jean-Michel Basquiat, who became a friend. “Basquiat used to come all the time,” he remembers. “He discovered that I had been working for Dalí for many years, and he wanted me to introduce him to people.”

The young artist, pre-fame, would make art at Raúl’s Brooklyn framing studio. “We never kept it because Jean-Michel Basquiat was nobody. He was doing graffiti on the street. He used to come and paint the windows, the doors, every day. When he found spray paint or crayons, he would just paint all over. In the winter, he would do the floors inside.”

In the subsequent decades, New York’s art community transformed in ways that changed what Raúl did.

“To tell you the truth, I was friends with most of the artists I worked with,” he said. “In order to make a frame, I have to know the person. That way, I know that the artist is going to like it and I’m going to like it. But most of my friends passed away. AIDS took care of many, many of my friends.” (Through Basquiat, he also knew Keith Haring, who died of complications of AIDS in 1990.)

Bigger economic shifts in the business were afoot as well. Carved frames were displaced by industrially produced frames from China. About this shift, Raúl is matter of fact. “I understand the collectors: a frame costs me $2,000 to make, and you can get something similar for $250 on the street,” he says. “It’s not the same, but you don’t want to show the frame anyway. You want to show the painting. The framing business, at least in New York, disappeared.”

He has, however, shifted and adapted. With his family, he now runs a small workshop in the Bronx where he makes bespoke hand-carved furniture, MarGian Studio. (The name is a synthesis of the first name of his wife, Maria Antonieta, who serves as studio manager, and his own last name.) Each piece is unique and made with rare materials. He insists on calling them “sculptures.”

The Mongolian Longhaired Stool from MarGian Studios. Image courtesy MarGian Studios.

Glimpsed online, MarGian Studios’s wares brim with multifarious personality. In some, like his shaggy Mongolian Longhaired Stools, witty Origami Swan Sidetable, or confounding Which Direction Sideboard, you might even get a flash of Dalí’s influence shining through.

A few years ago, Raúl had an accident. It left him with a herniated disk, and his left leg suffers debilitating pain if he spends too much time on his feet. “I don’t know when this will be, but I need surgery,” he says. Given the pandemic, it will not be anytime soon.

Now he can’t work unless he is sitting down, aside from doing general design for the studio. That’s what led him to take up driving. “I’ve come to know more of New York City than I knew in all the years that I have been in the United States,” he says. “I can talk to people, look around, distract myself. Whenever I’m in pain, I try to drive a taxi.”

In March, when he spoke with the Times on the cusp of the city’s shutdown, Raúl was still driving, even as life in the rest of New York shuddered to a halt. The intensity of the pandemic gripping the city has now made him think that to be unwise. Years of working with wood dust, marble dust, and chemicals have left him with chronic bronchitis. He no longer feels he can risk it ferrying passengers around the city.

“I’m 75 years old,” he says gently. “I plan to live many more years.”

I’m tempted to make some kind of bigger point about the meaning of all this. Somehow, Raúl Giansante’s story does seem to serve as a reminder about a lot of invisible work, a lot of lives sustained out of the Klieg lights trained on art’s center stage. It also passes through an astonishing cross section of the twists and turns of the last three quarters of a century, from Argentina’s political ruptures to the heady highs of New York in the ‘80s to the losses of the AIDS crisis to the dislocations and reinventions of the decades defined by globalization to, finally, the difficulties of coronavirus.

Mainly, though, if I’m honest, I’m telling you Raúl’s story because he’s an interesting person I wouldn’t have come into contact with if it weren’t for this time of turmoil and isolation. That serves as a tiny beacon to me that some new sense of connection might be snatched from the jaws of a terrible moment.

I look forward, some time in the future, to getting on the subway again, heading up to the Bronx to see his workshop, and greeting him in person.