The bustling city is visible outside its tall glass walls, but inside the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, there is a pristine kind of quiet. Little stirs except Alexander Calder’s large mobiles, which are gently spinning from an indiscernible wind. They are part of a monumental first exhibition at the German museum, which is opening for the first time in more than six years on August 22.

One who did not know it would hardly guess the entire museum, designed by Mies van der Rohe, was just turned inside out. The bi-level museum has been meticulously restored by David Chipperfield Architects, paid for by the federal government. Few would argue that the €140 million ($168 million) renovation was unnecessary: The building had fallen into disrepair, with rust, cracks in the glass, and a pesky issue with condensation, among a longer list of issues.

Six years on, entering the museum is somewhat like stepping into a deep past. Chipperfield, who worked with the brief to maintain “as much Mies as possible,” had his team dismantle the structure of glass and steel piece by piece, and each element was painstakingly restored to be as true as possible to the day the museum was unveiled to great acclaim in 1968. The architect died a year later; the building was his last.

Exhibition view of “The Art of Society 1900–1945: The Collection of the Nationalgalerie,” 2021. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / David von Becker

Even a famous Calder piece that was there on that postwar opening day has returned. For the Calder exhibition “Minimal/Maximal,” Têtes et queue (1965) is back on the terrace where it stood, in what was then West Berlin. Dark carpets and restored Barcelona chairs, the celebrated seats made by the architect, are back on view and ready for guests.

In the lower level, one finds the restaurant, renewed thanks to artist Jorge Pardo, who has created a contemporary intervention that sensitively draws on the room’s Anni Albers motifs, employing Mexican-Spanish references.

Contemporary positions like Pardo’s will also be presented in temporary shows. Rosa Barba has the first slot, with a major installation called In a Perpetual Now, and more female contemporary artists, including Barbara Kruger and Monica Bonvicini, are on the docket. In 2026, the museum will host works from the Centre Pompidou in Paris when it closes for its own long-overdue renovation.

Alexander Calder Untitled (1954). Calder Foundation, New York; Gift of Andréa Davidson, 2007. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. VG-Bildkunst, Bonn 2021 / Photo by David von Becker

The main rooms feature a presentation of the museum’s esteemed collection of modern art, which was painstakingly rebuilt after almost all of it was looted and lost during World War II. Since then, the holdings have outgrown the space capacities of the building, so a new and somewhat controversially-designed structure has broken ground next door to house a good portion of the collection, which waits in storage until the new space is ready in 2026.

Like the building’s redesign, its first show, “The Art of Society 1900–1945,” also takes us back in time. The highlight opener is a poignant painting by German painter Lotte Laserstein’s Evening Over Potsdam (1930). A group sits outside, looking forlorn; in the background dark clouds reflect the looming rise of National Socialism. The museum bought it in 2010 at Sotheby’s for £421,250, according to the Artnet Price Database.

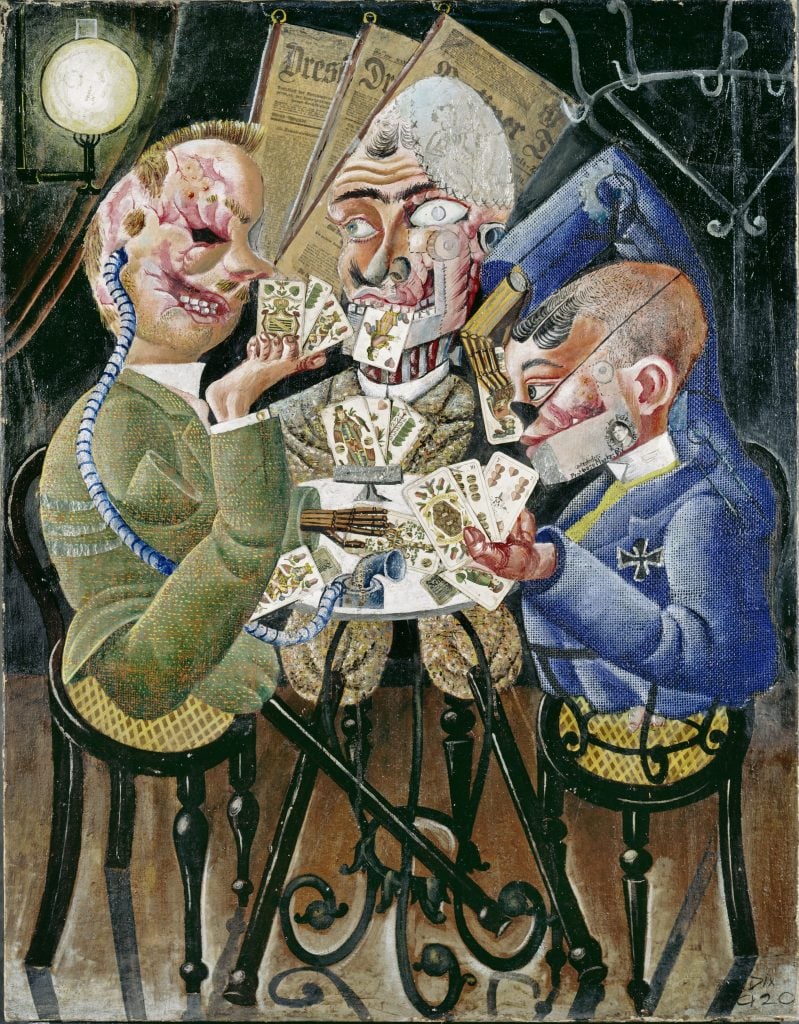

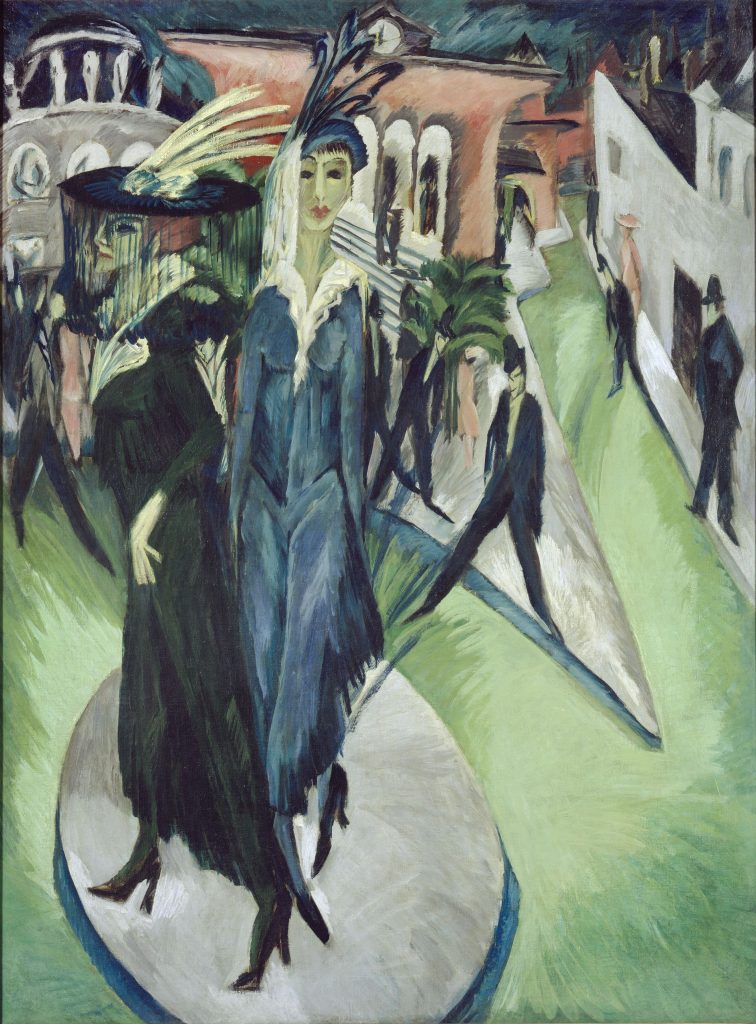

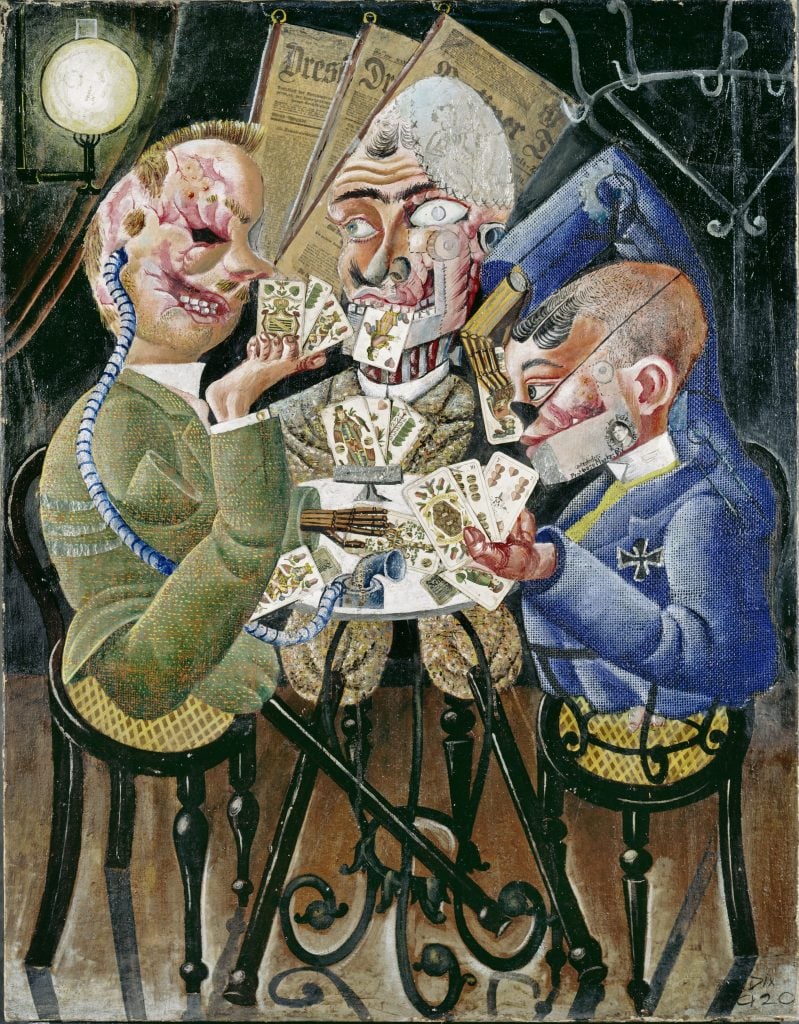

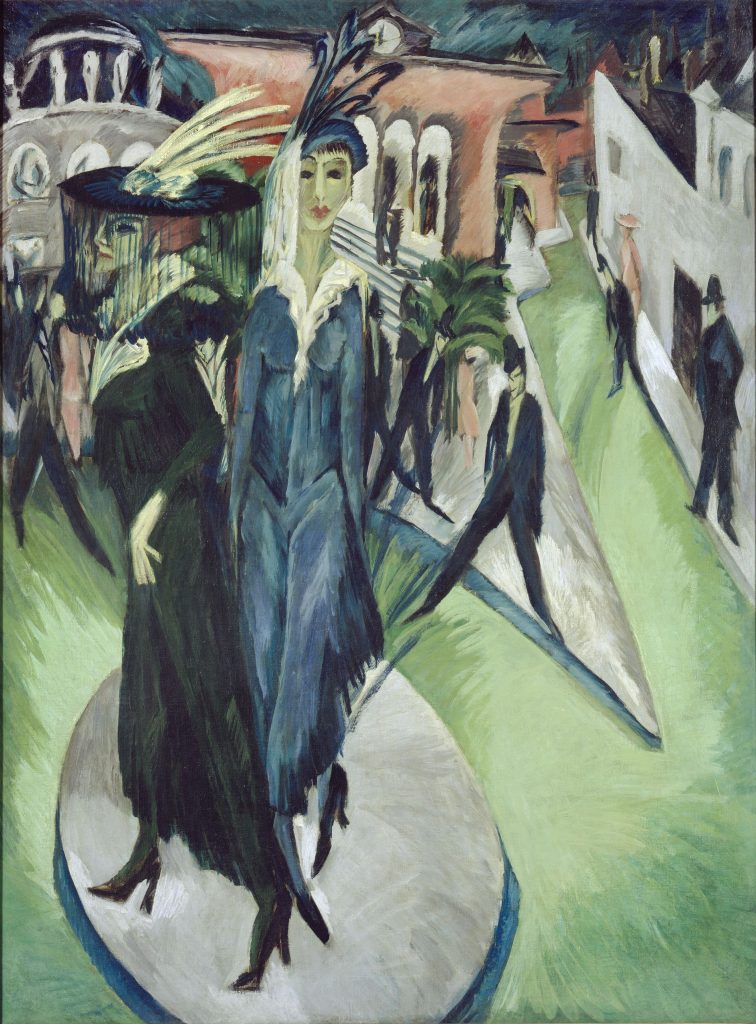

Other areas focus on European art and the cultures that informed and surrounded the artists between 1900 to 1945. There is Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s absinthe-soaked canvas Potsdamer Platz from 1914, which shows a landscape from nearby the museum that was totally flattened about three decades later. Powerful pictures evoke the devastations of World War I, too, like Otto Dix’s Die Skatspieler from 1920—a psychedelic collaged painting depicting amputee veterans with machinelike limbs.

Lotte Laserstein, Evening Over Potsdam, 1930. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021.

Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Roman März

The museum will continue to focus on western modernism, in all its highs and lows; however, while the building may have been restored to the past, there are moments that bring it into the future, such as new didactic panels that address the racist gaze present in works by painter Emil Nolde and his cohort, made during colonial times in the South Pacific.

At a recent press preview, the museum’s director lamented gaps in the collection, which he is eager to fill. “My hope is that we can add to the collection these positions that are missing,” Joachim Jäger said, noting that despite a limited collecting budget, he would love to bring more diversity into the collection. At the top of his list are long-overlooked artists like Irma Stern and Hilma af Klint, the latter of which has a work currently on loan for the show.

See more images of the exhibitions and galleries below.

Alexander Calder, Têtes et queue, 1965, from “Minimal/Maximal. “Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Photo: Stephanie von Becker

Exhibition view of “The Art of Society 1900–1945: The Collection of the Nationalgalerie,” 2021. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / David von Becker

Otto Dix, Die Skatspieler, 1920. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021. Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Jörg P. Anders

Exhibition view of “The Art of Society 1900–1945: The Collection of the Nationalgalerie,” 2021. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / David von Becker

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Potsdamer Platz, 1914. © Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Jörg P. Anders

Exhibition view of “The Art of Society 1900–1945: The Collection of the Nationalgalerie,” 2021. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / David von Becker

“The Art of Society 1900–1945,” Alexander Calder’s “Minimal/Maximal,” and Rosa Barba’s “In a Perpetual Now” open at the Neue Nationalgalerie on August 22.