Artnet News Pro

Speculation Threatened to Derail Dana Schutz’s Market. Here’s How She and Her Dealers Rebuilt It on Solid Ground

Dana Schutz's market offers an object lesson in how to survive speculation.

Dana Schutz's market offers an object lesson in how to survive speculation.

Eileen Kinsella

The return of Frieze New York in May not only marked the first major physical art fair in the city in over a year—it also served as the first public outing for an auspicious new artist-gallery relationship. David Zwirner presented a suite of new works by Dana Schutz, the megawatt artist it signed last fall.

Over the past two decades, Schutz, 45, has become famous for her wildly colorful, surreal canvases that blend figuration and abstraction to convey complex psychological states and ambiguous narratives that are equal parts scathing and humorous.

Dana Schutz, The Fisherman (2021). Courtesy of Christie’s Images, Ltd.

By the end of the first VIP day, all of her new paintings, priced at a newly increased level of $700,000 to $900,000, and sculptures, priced at $160,000 to $250,000, had sold. Schutz’s star rose even higher that same week, when she donated a major new work, The Fisherman (2021), to a Christie’s New York auction to benefit land conservation charity Art Into Acres. Estimated at $400,000 to $600,000, it soared to $2.9 million, becoming the second highest price at auction for the artist.

Schutz is a rarity in today’s overheated contemporary art market. Although she burst onto the scene as a commercial darling in the early 2000s and quickly became the subject of fierce speculation, she has managed to avoid the pitfalls that have led other super-hot artists to flame out. Through careful editing of her own work, canny alliances with dealers, and a dedication to innovation, she has managed to build a market that is now experiencing a second renaissance on much firmer ground.

Some wondered whether the controversy that engulfed Schutz during the 2017 Whitney Biennial would derail both her legacy and her market. Her painting Open Casket (2016), which presented her interpretation of the historic photograph of a mutilated Emmett Till, divided the art world and drew fierce opposition from those who believed a white woman should not appropriate images of Black trauma.

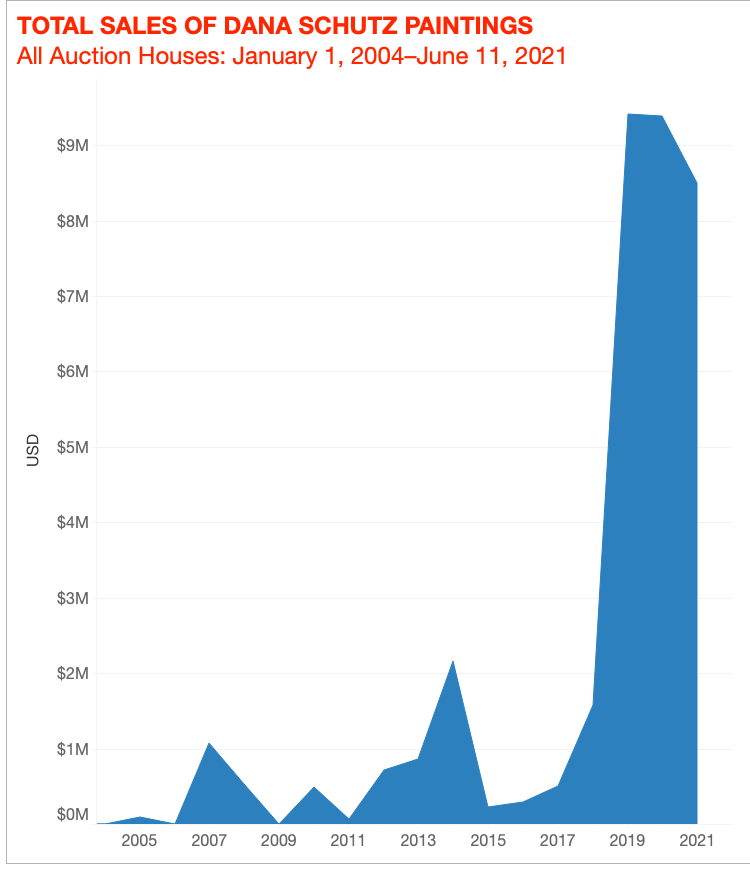

The uproar caused Schutz to withdraw for a time—she did not have another major show of new work until 2019—but it did little to lessen demand long-term. The artist’s 14 highest auction prices have all been set in the past two years, including the record $6.5 million paid at Christie’s Hong Kong in December for Elevator, a Cubist-inspired painting of a crowd squeezed into an elevator.

© Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics 2021.

The average price for a Schutz painting at auction has also more than doubled over the past two and a half years, from $671,860 in 2019 to $1.7 million in 2021. To date, nine of her works have sold at auction for more than $1 million—and six of those sales have taken place this year.

“The profile of collectors that are looking to buy her work is completely international,” Christie’s senior specialist Ana Maria Celis said. “Even at the very top, meaning the people bidding neck to neck, it’s Europe, America, Asia,” as opposed to one region, she noted.

Schutz burst onto the scene in the early 2000s, when her debut with art student-turned-dealer Zach Feuer sparked a feeding frenzy. Collectors jostled for the chance to buy her “Sneeze” paintings, which depicted a violently exaggerated version of the act, and her “Frank from Observation” series, featuring a nerdy man as the last one on earth.

“The danger signals came almost immediately,” Calvin Tomkins wrote in a New Yorker profile of the artist in 2017. Feuer sold one painting, The Breeders, to a New York collector for $8,000; within a year, that same collector flipped it to mega-dealer Larry Gagosian in a private sale for about $500,000.

These kind of erratic price spikes—especially when they occur at public auctions—can derail a market by irreversibly skewing the pricing structure. Feuer called it a “wake-up call”; Gagosian later admitted to Tomkins that he had overpaid, but explained that “you couldn’t get a work of hers otherwise.” (Feuer, who has since left the art-dealing business and now lives in upstate New York, declined to comment for this story.)

Installation view of Dana Schutz’s new work at David Zwirner booth, Frieze New York, at The Shed. Image courtesy David Zwirner Gallery.

The gallerist attempted to regain control of Schutz’s market by selling only to buyers who promised to donate the works to museums or offer the gallery right of first refusal instead of flipping them at auction. But he could only do so much.

In 2007, Schutz’s painting Night in Day (2002) sold for almost $288,000 at Christie’s, which far exceeded her primary market pricing at the time. Her auction prices began to stagnate after that as tastes began to shift toward the so-called “Zombie Formalists,” whose work put a contemporary twist on Abstract Expressionism.

Top collector Charles Saatchi, who had bought two of Schutz’s early paintings from Feuer, bought more than a dozen from other collectors at hugely inflated prices after Feuer refused to sell him more. Eventually, Saatchi offloaded nearly all of them—and not necessarily for a profit, according to Tomkins.

“The hyper-inflated prices didn’t last,” Tomkins wrote. But thanks to major museum shows at the Denver Art Museum, the Miami Art Museum, and other institutions, “her reputation kept growing.” As it turns out, this cooling off period was just what the doctor ordered.

So how exactly did Schutz survive the speculation machine? First, she kept working—steadily, but not prolifically—over the next decade. “She happens to have not only a talent for art, but also for self-editing,” the art advisor Todd Levin said. “The things that she chooses to release that go out into the world tend to be of uniformly high quality.”

In 2012, Schutz joined the highly respected gallery Petzel, which is no stranger to navigating art-market shenanigans (it also represents Wade Guyton, whose prices were going gangbusters at auction in the mid-2010s and have since found stability). During her time at Petzel, Schutz was careful to modulate her output, staging a measured three solo shows over the course of nine years.

Petzel, which declined to comment for this story, had slightly more muscle than Feuer to enforce the typical anti-speculation playbook. That included prioritizing institutional placement (three of the works in her debut show in 2012 went to museums) and incorporating resale terms into contracts. Although such terms are widely considered unenforceable legally, those who violate them are likely to be blacklisted by the gallery—which means the more powerful the gallery, the more likely a collector is to adhere to the terms.

Petzel also steadily raised her prices, from around $200,000 to $300,000 in 2017 to around $400,000 or $500,000 two years later, according to sources. As a result, her market no longer had “that kind of early-career price action dynamic to it anymore,” Levin said.

Dana Schutz, Elevator (2017). Image courtesy Christie’s.

Then, in 2020, Schutz’s move to mega-gallery Zwirner put her in the hands of one of the most powerful dealers in the world. “We always work with an eye toward placing her works in suitable collections and with institutions,” Zwirner partner Branwen Jones said.

The gallery reportedly signed Schutz with a hefty advance, though the fact that it also raised her prices further, to $700,000 to $900,000, combined with the sold-out Frieze presentation, suggests it was a lucrative arrangement for both sides. Plus, at today’s primary market prices, even wealthy collectors have to think twice before dropping nearly $1 million on a painting with the intention of turning it around for a quick buck.

Dana Schutz, Civil Planning, 2004. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Not surprisingly, the strategies to shut down speculation on the primary market pushed up Schutz’s prices at auction. Those who could not get access to Schutz’s work from a gallery were increasingly likely to battle it out on the auction block.

The artist “has had this very long, steady growth in her market as well as progression in terms of the creation of her art and style and how it has evolved,” Phillips international specialist Kevie Yang said. “If anything has changed, it’s that now the pool of buyers and collectors has gotten much bigger and more global.” Demand from Asia in particular has fueled Schutz’s auction performance in recent years, she added.

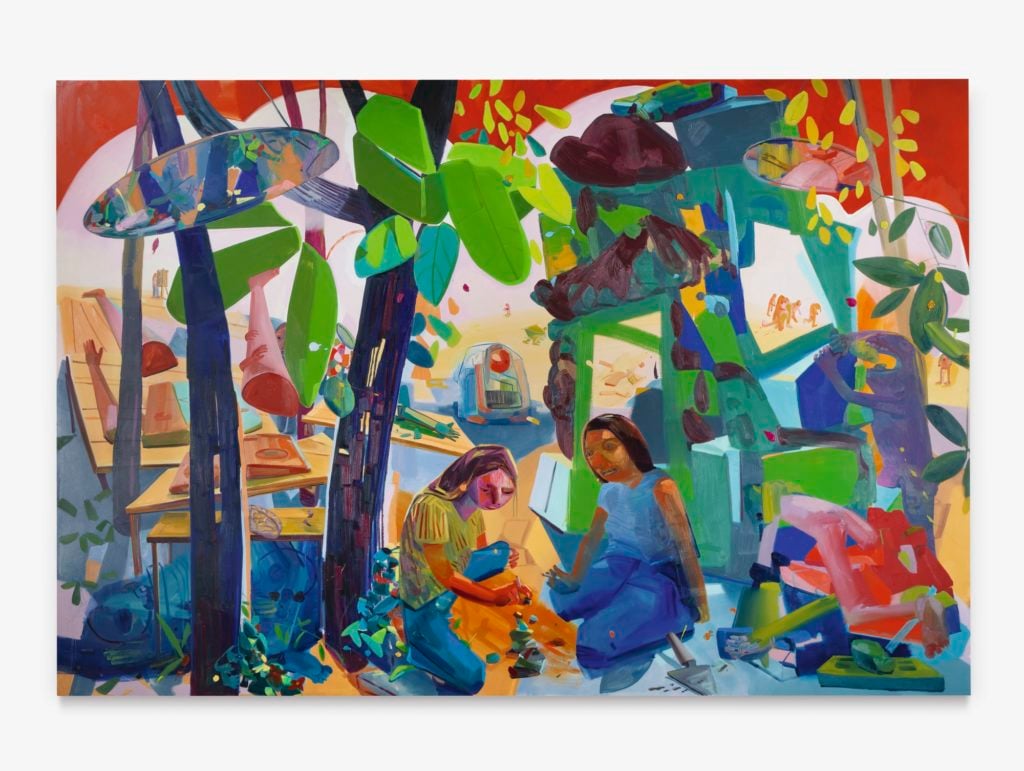

In May 2019, the artist’s record was broken twice in the same night, culminating with the sale of Civil Planning (2004), a monumental garden scene that fetched $2.4 million at Sotheby’s New York. The work was sold to benefit the foundation of the late management consultant David Teiger. In a classic case of a promise falling short, Teiger had originally pledged to donate the work to the Museum of Modern Art when he bought it in 2004, according to Feuer.

It was during this sale that interest from Asian collectors first took hold “and the market has skyrocketed the past three years, breaking record after record,” Sotheby’s contemporary art specialist Elizabeth Webb said.

Dana Schutz’s New York studio, 2012. © Marco Anelli.

Schutz’s trajectory also reflects a broader shift in taste. After years of favoring abstraction by younger, emerging artists, collectors have enthusiastically embraced figurative work, particularly by female artists.

“All these artists that people want to collect now are doing figurative work,” Christie’s Celis said. “I think Dana is just the example of the artist that has been doing it for longer and she has mastered it at this point.”

The fact that Schutz has managed to create discrete, unique bodies of work has also encouraged collectors to engage in-depth, rather than buying just one to check it off a list. That’s part of why, even at auction, works from across her career have seen strong prices.

The more grotesque, goofy, early paintings may be a slightly harder sell to an international audience (think: cannibalism, bodily fluids), but her images of large groups in dramatic settings—such as those from her 2015 Petzel show “Fight in an Elevator,” inspired by the leaked video of Solange attacking her brother-in-law Jay Z—as well as her more pleasant outdoor scenes are particularly sought after. Today, her work is “more serious and politically charged,” Celis noted.

Dana Schutz, Conflict, 2017. Oil on canvas, 94 x 82 in. (238.8 x 208.3 cm). Courtesy the artist and Petzel Gallery, New York. Photo by John Kennard. © Dana Schutz

The 2017 Whitney Biennial painting—which curators ultimately decided to leave in place with a new wall label acknowledging the controversy—did put a chill in Schutz’s market, but only temporarily. (Schutz removed the work from circulation after the exhibition and never intends to offer it for sale.)

Noting that only four paintings by Schutz came to auction in 2017, Sotheby’s Webb said that “it was clear that collectors who owned work opted to hold back on selling as this conversation unfolded surrounding cultural appropriation by white artists.” Perhaps ironically, however, “while the market may have paused, the dialogue and interest amongst collectors did not…. For some, it was this event that brought them to look further at Schutz career.”

For her part, Schutz has given only occasional interviews since the controversy, preferring to let her paintings speak for themselves. “Is it better to make something that’s impossible, because it’s important to you, and to fail, or never to engage with it at all?” Schutz asked Tomkins at the time. “I just couldn’t do it any other way.”