People

Decades Ago, Richard J. Powell Was Among Only a Handful of Scholars Dedicated to Black Art History. Here’s How He Has Seen the Field Change

Part of a series of interviews with art historians engaging with Black cultural history.

Part of a series of interviews with art historians engaging with Black cultural history.

Folasade Ologundudu

This article is part of a series of conversations with scholars engaged with Black art for Black History Month. See also Folasade Ologundudu’s interviews with Bridget R. Cooks, Darby English, and Sarah Lewis.

***

Richard J. Powell literally wrote the book on Black art history—specifically Black Art: A Cultural History, from Thames & Hudson’s World of Art series. That groundbreaking volume has served as an introduction for several generations of students.

As a historian specializing in African-American art history, the Chicago-born scholar’s expertise lies in his astute understanding of the history of Black cultural life in America. Graduating from Morehouse College with a B.A. in art and from Howard University with an MFA in printmaking in 1977, Powell went on to receive his Ph.D in the History of Art from Yale in 1988. Since 1989, he’s been John Spencer Bassett Professor of Art & Art History of Art & Art History at Duke University.

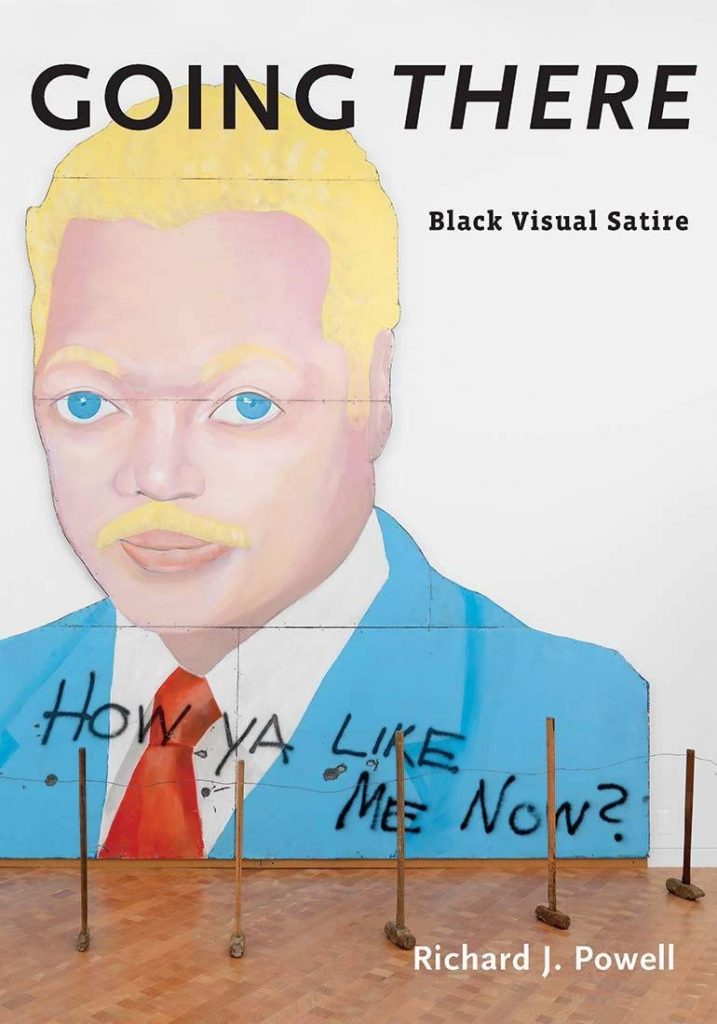

In fact, it may be more accurate to say that Powell wrote the books on Black art history. Among the many volumes of scholarship that Powell has published are works as wide ranging as The Blues Aesthetic: Black Culture and Modernism (1989) and The Obama Portraits (2020) (co-written with Táina Caragol, Dorothy Moss, and Kim Sajet). His latest is Going There: Black Visual Satire (2020), which looks at the work of figures from Kara Walker to Spike Lee.

Recently, I spoke with Powell about how he got his start writing about art, what parts of art history he thinks remain unexplored, and how the field has changed and continues to evolve.

How did you come to being a scholar of Black art? And what was your path into the field?

My path to becoming an art historian began as a practitioner: I studied art as an undergraduate, and I majored in printmaking. While making art I was in conversation with writers, poets, and historians, planting the seeds for me eventually becoming an art historian. It wasn’t until I got to Howard where I saw people who were writing the history of art.

The epiphany moment was after getting my MFA. I applied for a fellowship at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This is 1977. While there, I interacted with people in the New York art world. I spent time at the Studio Museum in Harlem. That was where I first started doing art criticism.

How has the reaction to your work changed over the years?

When I first started writing and doing research, it was for a very limited audience. Some of the first things that I wrote were art reviews. I remember doing a review of a performance at Just Above Midtown that included Houston Conwill and David Hammons. That piece ended up being published in a journal in Los Angeles. I wrote a review of a Benny Andrews book that appeared in Emerge, a magazine doesn’t exist anymore.

This was also a moment early in my life where I finally was able to curate my first exhibition. I did an exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem at the beginning of 1980 called “Impressions/Expressions: Black American Graphics.” The audience for these projects was relatively limited, but I was pleased that my work was getting out there to some extent.

The catalogue for “Impressions/Expressions: Black American Graphics,” curated by Richard J. Powell.

I kept on applying away and continuing to write and continuing to publish. I remember getting my first big published piece in African Arts Magazine in the mid-‘80s: a profile on the African art at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. By that point I was beginning to work on my dissertation on the artist William Henry Johnson.

So, it’s a cumulative process. You continue to work, you continue to write, you’re not deterred because you don’t have a huge profile. You write because you’re passionate about the subject, because you think you have something to say and a buy-in from an audience. Art historians still have a fairly limited audience for what we do—but I think what we do is important.

I would say that the reaction has been increasingly positive—perhaps more and more so, in terms of the current moment and people’s enthusiasm for arts of the African diaspora.

What is the status of African-American art history within the discipline of art history today? Is progress being made?

That’s a really good question. When I started doing research and staked my claim as someone interested in African American art, there were very limited places where one could do that and where one would be treated seriously.

I was very lucky to have been at Yale in the early ‘80s when Robert Farris Thompson, the very eminent art historian of African art and also arts of the African diaspora, was teaching. He thought my project on an African-American artist was worthy to be a topic for a dissertation. I also worked with Jules Prown, a preeminent Americanist. Both of them really encouraged to me. This was rare because I think most art history departments in the ‘80s would’ve looked askance at somebody who was going to write about Black American artists.

Things have changed. It’s kind of a remarkable shift that in 2021 many departments of art history, many curatorial departments and museums, are feeling that they really need someone to address these aspects of modern and contemporary art.

Are there still specific areas or figures in African-American art history that have been under-researched, under-explored, or whose impact has been underestimated?

There are many people out there who need more attention. The first one who comes to mind is a man named Julian Abele, who was a major architect at the beginning of the 20th century. All indications are that his designs were responsible for the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the library at Harvard university, the mansion on Fifth Avenue where the Institute of Fine Arts is now located on New York University’s satellite campus. And yet there’s not been a really serious study that looks at him and thinks about what it meant to be a Black man doing these major projects at that time.

Portrait of Julian Francis Abele. (Photo courtesy Duke University, via Wikimedia Commons.)

In my latest book, I tell a short version of the story of Ollie Harrington, another person whom I think deserves a greater depth of exploration. He was a cartoonist. Maybe that’s part of the reason why no one has looked seriously at him, but this was an incredibly talented guy. He was an international figure working in Paris, in Germany, traveling the world. He was in Ghana near the creation of the nation. His work is powerful and political—but because he was political, I think there’s been almost a suppression of his story.

Cover of Ollie Harrington’s book Why I Left America and Other Essays (1993).

That’s just the tip of the iceberg of so many historical figures who come out of the Black world whose works still need to be looked at and written about.

And that’s a common thing you see throughout history: the work of African-Americans, the work of folks from the African diaspora, is lost to history. In fact, Black art and artists’ contributions are often both systematically and deliberately suppressed.

It’s a complicated situation because these artists were viewed in ways that dismissed them and their work. What’s exciting about being in the world in 2021 is that there’s at least lip service to saying, “we’re going to do better, we’re going to think deeply about this thing called Black art.” There’s so much more room to dig back into history and retell these stories. These are important Black artists who stand up alongside the Picassos, who stand up alongside all of the people who have been given hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of shows.

The systematic erasure of African-American art through a lack of criticism, press, and media attention has been prevalent for hundreds of years. How did this shape movements such as the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and ‘30s and the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s? Were Black artists of the Renaissance and BAM creatively responding to a lack of criticism and a claim of their creative talents and abilities?

There could have been artists who were prompted to work as a statement against the blindness towards their creativity and their genius. But I would say that the major impetus in the 1920s and the 1930s, and also in the 1960s and 1970s, was a desire on the part of Black artists to respond to their times.

I’m teaching a seminar right now on the Harlem Renaissance and it’s so clear when we look at the works of Aaron Douglas and Loïs Mailou Jones and Richmond Barthé and others that they’re picking up on this excitement in the world, when Black people are making important statements in culture and trying to break away from a racist system. That is their motive more than if somebody from the New York Times was going to write about them or if a museum wanted to hang their work. That was not the reason for making art; they made art because they had to make it.

Installation view of “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” at the Brooklyn Museum. Photo by Jonathan Dorado, courtesy the Brooklyn Museum.

In the ‘60s and ‘70s, which I’m more familiar with because that’s closer in my time, the media became really important and artists from Elizabeth Catlett, Charles White, Romare Bearden, and Barkley L. Hendricks were aware of that. It’s great that we have these works that were produced as seen in the “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983” show that touched on the agitation and anxiousness of the post-civil rights movement. That’s what makes these works doubly exciting: not just a one-dimensional approach to protest and education, but a more veiled, layered, and nuanced meditation on Blackness.

In your latest book, Going There: Black Visual Satire, you surmise that Archibald Motley, an artist of the Harlem Renaissance, in the context of satire, “opened floodgates of racial memories, phobias, and fantasies, so visceral and inescapable that, upon experiencing them, more authentic concepts of the race could emerge.” Can you speak to the ways in which satire created a space for new conversations to emerge regarding assumptions of Black life and the ways African-American artists turned those stereotypes on their heads by taking ownership and interpreting them in their own way?

Step back from Motley and think about culture and how people communicate with one another, and how in particular Black culture has interesting and provocative ways of expressing feelings and emotions. Sometimes communication operates not using words at all but using your face or your expressions or your body in particular ways. What I attempt to do in this book, through the lens of artists like Archibald Motley and Robert Colescott and others, is to show how visual artists use discursive devices that sometimes include complicated and problematic materials in order to make dramatic, provocative, and sometimes critical statements—and this is not new. We do it among ourselves.

Cover of Going There: Black Visual Satire by Richard J. Powell.

What makes Black artists so fascinating, particularly in the 20th century, is that they often take these tools and these elements that were used to denigrate them and they use them as vehicles to make a statement against systemic racism, against violence, against prejudice, against the absurdities of Jim Crow. That’s what makes contemporary art so interesting and so challenging for some people. Motley will get images that speak to elements of stereotypes not to underscore those stereotypes but to trigger our feelings, phobias, fears, and anxieties around class.

This connection is one that I’ve seen throughout African-American and Black history in the ways we talk to each other and communicate with each other. It’s very singular and unique.

As someone who’s been looking at art over the years and been in conversation with people about art over the years, in doing this book I was trying to explain that the artists have their ear on our culture—on how we operate, how we function. Many of these artists have an agenda to call out injustice or hypocrisy, and they find very innovative and provocative ways of doing that.

Absolutely. Would you argue that Motley’s satire of the pretentiousness of White America and its elite ideologies helped to spark what would become known as the Black Art Movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s that coincided with the Black Power and Black Is Beautiful movements of the same time period?

Motley is a unique character because his career is a part of the New Negro Arts Movement or the Harlem Renaissance. By the ‘60s, he’s an elderly man, still working. I think he serves as a role model for artists of later generations. This is someone who really understands the beauty and the power of our people and particularly our elders. He does provide some models for artists, but at the same time it is another moment in the ‘60s and onward, so I wouldn’t want to draw too straight a line.

Archibald J. Motley, Jr., with one of his paintings, at the Chicago Artists’ show at the Art Institute.

(Image courtesy Getty Images.)

How does taking agency over one’s own history shift power to those who have been historically oppressed, in art and in life?

I’m thinking again about the Harlem Renaissance class that I’m teaching now and what the preeminent philosopher, Alain Locke, writes a book called The New Negro. One of the things he says in the book that my students brought to my attention in a big way was how “The New Negro” represents this emerging Black consciousness in the ‘20s and ‘30s as a form of self-portraiture. When you use the word “agency,” that really distinguishes the modern moment in the 20th and 21st century: African-American scholars, critics, theorists, curators, and obviously artists are taking control of language, analysis, and investigation of their own culture. As you just said, that really shifts the power when it comes to how we engage with Black culture and Black society.

I feel very fortunate to have been a product of HBCUs [Historically Black Colleges or Universities]. We were within a world where we didn’t have to question our identities and abilities to interrogate, because it wasn’t about Black vs. White. It was about thinking and interrogating our culture.

Black Lives Matter has opened up a huge conversation about representation. What opportunities do you see for the field of art history and Black historians? If at all, do you think that there are pitfalls as well?

It’s a reverberation of other moments in time where people have stood up and said, “enough is enough.” Black Lives Matter is in some ways a 21st century reverberation of “Black Is Beautiful” and “Black Power,” and “Black Power” was a reverberation that hearkened back to the 1920s and ‘30s to the Jazz Age and the Harlem Renaissance. So, we’ve always had these periods in Black America, intermittently, where a particularly vocal and expressive movement says, “I matter, I exist.”

So definitely: Black Lives Matter. If it takes that kind of proclamation to get people excited, to get people worked up, to get people thinking about representation in our institutions, then so be it. If that’s what it takes to get the fields of art history and the other humanities to take stock and reflect on what they haven’t done and what they can do to create a more diverse and more truthful representation of cultural production—if Black Lives Matter is what does that, so be it.