Art World

Motivated by ‘Rage and Hopelessness,’ Robert Longo Takes Aim at American Gun Violence in an Epic Work for Art Basel

The monumental sculpture at the fair's Unlimited section is made of 40,000 shell casings.

The monumental sculpture at the fair's Unlimited section is made of 40,000 shell casings.

Tim Schneider

Although the photorealist virtuoso Robert Longo has been making politically charged work since his rise to prominence in the Reagan era, the blood tide of American gun violence has driven him into new territory.

“Rage and helplessness is a real motivating thing for me lately,” the artist told artnet News by phone, just hours before departing for Art Basel. Sometimes his work provides a “weird sense of atonement, because I just can’t believe this shit is happening.”

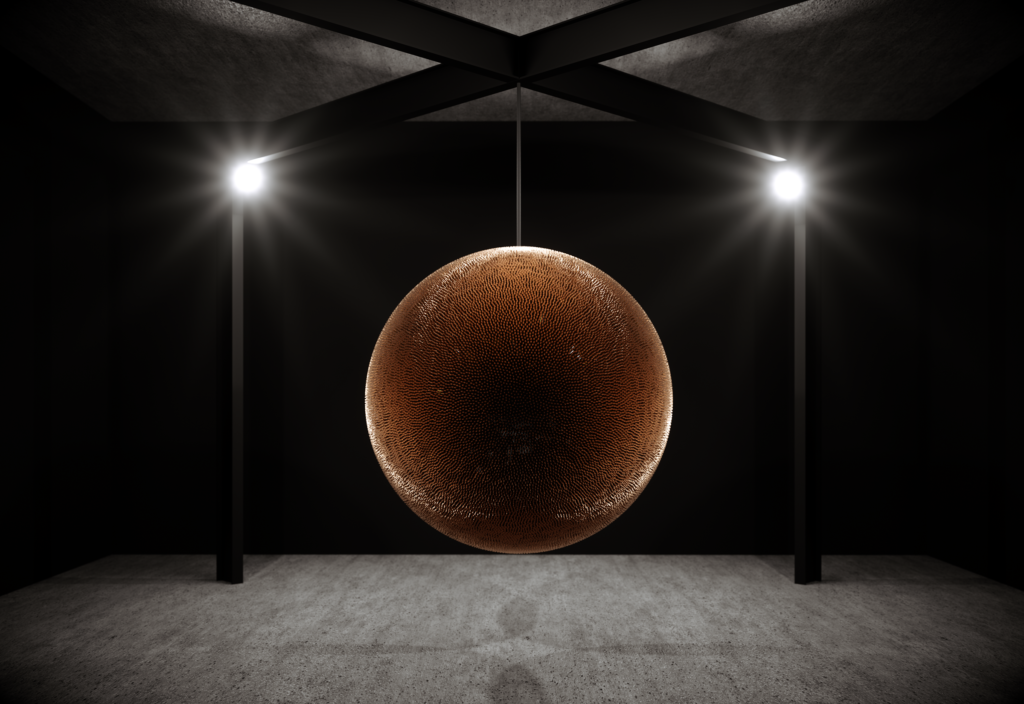

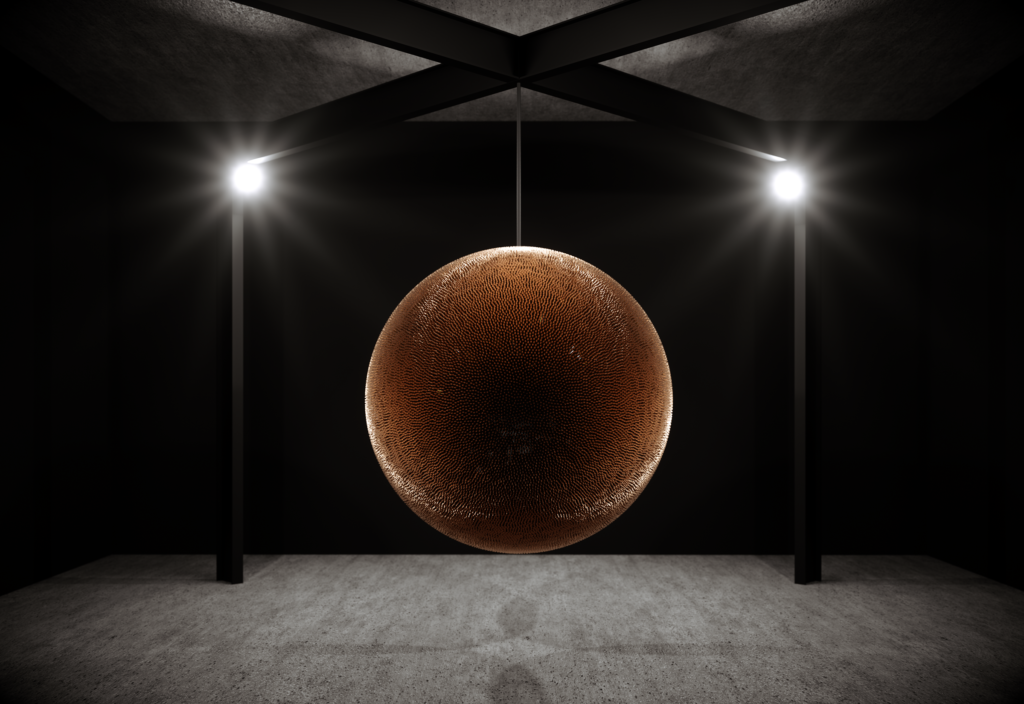

The latest work forged from Longo’s inner turmoil is a sculptural installation on view in the fair’s Unlimited section, debuting to press and VIPs on Monday. Alone inside a gray-painted space hangs a mysterious copper orb, nearly six and a half feet in diameter, suspended from a sturdy, minimalist I-beam structure. From a distance, the orb’s core radiates only a subtle ambient light, while strategically positioned spotlights ensure that its outer rim glows like the halo of a solar eclipse.

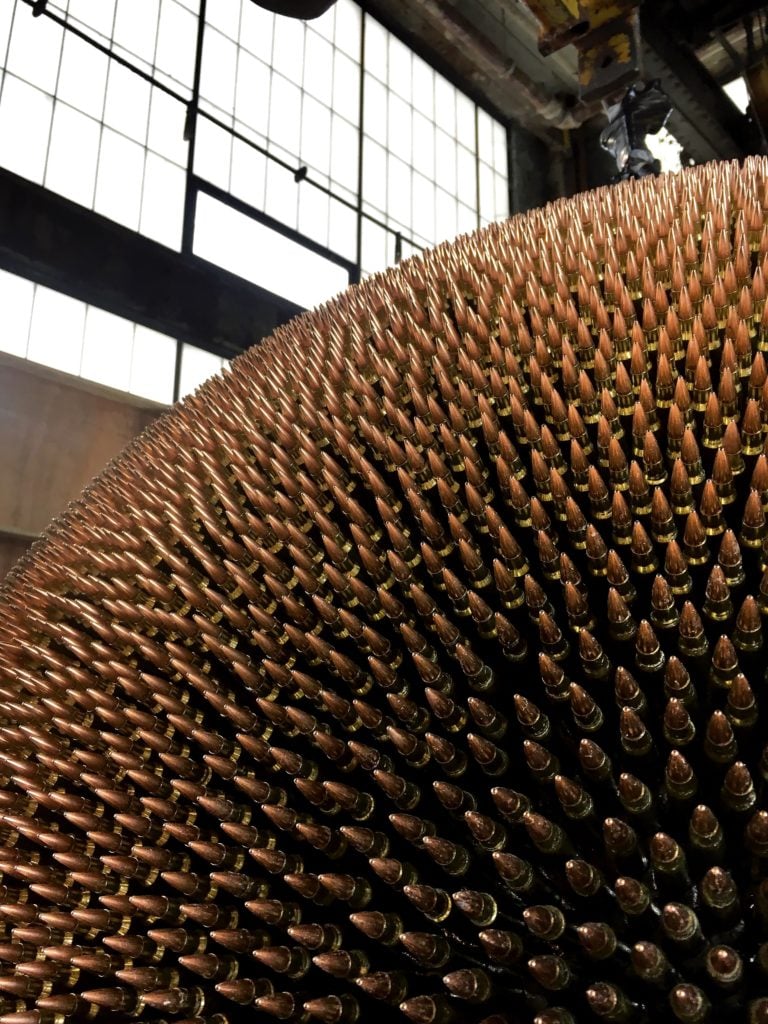

It isn’t until viewers draw much closer to the shimmering surface that they see its alluring, illuminated topography consists of polished copper shell casings. About 40,000 of them, to be more precise—roughly one bullet for each gun death in the US last year.

Co-presented by Metro Pictures and Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Death Star 2018 is the result of Longo asking himself a very specific question about firearm-inflicted violence in America: “How do you give this insane statistical abstraction that is as brutal as it is a material form?”

At the same time, brutality is not Longo’s endgame. “This piece is not so much about shock and awe,” he says. “It’s more about creating some kind of beauty out of something that’s quite horrible, and at the same time hoping that it will make you personally [think], ‘What am I going to do about this [the gun problem]?'”

Robert Longo, detail of Death Star 2018 (2018). Image courtesy of the artist, Metro Pictures, New York, and Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac; London, Paris, Salzburg.

Longo first wrestled with this challenge 15 years earlier. The new “bullet ball” (as he short-hands Death Star 2018 in conversation) represents a harrowing sequel to an earlier, smaller piece created in 1993 that bore a nearly identical title.

The original Death Star—today held in the collection of Buffalo’s Burchfield Penney Art Cente—comprised a mass of only about 18,000 rounds of ammunition, symbolizing the roughly 18,000 American gun casualties the year before. (Longo excluded gun suicides from both Death Stars.)

In 2018, though, it isn’t just that the number of gun fatalities has grown. Their character has shifted, too.

Longo explains that the first Death Star had a very personal origin. His teenage son had seen a fight break out on a basketball court in New York, and someone pulled a gun. Although no one was hurt, the episode had a profound effect on the young Longo. In the artist’s recounting, his son realized that “he didn’t have to be the strongest anymore, or the toughest, or the most skilled guy. You just had to buy a gun and you were the most dangerous.”

That first got Longo thinking about gun violence, but the new work was particularly motivated by the mass shootings, enabled in no small part by American gun owners’ love affair with new weaponry. Whereas the 1993 bullet ball consisted of blank rounds for revolvers, Death Star 2018 takes shape from the shells fired by AR-15s and other commercially available assault rifles—all of them akin to the AK-47 that Longo estimates “has killed more people than any common bomb or anything else like that in the world.”

According to the artist, the bullets used to create the two Death Stars are a similar caliber, meaning they have tips about the same size. But assault rifle shells incorporate “more than twice the amount of gunpowder,” making them vastly more powerful than side arms.

“These automatic assault rifles, they’re basically devastating compared to a standard .38 caliber bullet that used to fit into a police revolver,” says Longo. Combined with their light weight and ease of operation, these weapons’ added force has made them incredibly popular in the US. “It seems to be the bullet of America’s choice these days,” he says.

Robert Longo, Death Star (1993). Image courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Longo went to great lengths to ensure that a sense of randomness and unpredictability informed the new work’s topography. While the original Death Star was constructed entirely in-house and by hand, Longo says that something unexpected happened during the long days and nights of manual application: patterns started to emerge in the arrangement of the bullets. Looking back, he now sees those unintended rhythms as subtly dissonant with the epidemic he was trying to address.

“Just like people want to hear narratives in a story, when we hear facts, people also want to see patterns,” explains Longo. So when American media outlets, politicians, and citizens try to process gun violence, they tend to “try to break it down into categories like mass shooting, gang shooting, murder, self-inflicted gun wounds, suicides. But there is no pattern to gun violence in the United States, except that there are just too many fucking guns!”

To capture the appropriate randomness in Death Star 2018, Longo collaborated with a former NASA engineer at Neoset Designs, a next-generation fabrication studio in Brooklyn. Together, they used advanced modeling to eliminate any sense of order in the surface of the bullet ball, making the sculpture truer to the reality of fatal shootings.

Weighing roughly 2,000 pounds, Death Star 2018’s cast-aluminum core bears an individual mounting hole for each of the roughly 40,000 bullets. For maximum precision, the channels were drilled by a robot. Yet the bullets themselves were glued and snapped into place by hand.

Since it’s now illegal in New York State to order blank rounds by mail, as Longo did for the original bullet ball, the artist had to transform his studio into a munitions factory for assault-rifle ammo. “We had to buy casings and the tips and a loader, and we had to put the bullets together,” he says. “But we did buy 40,000 bullets, and nobody came knocking on my door, saying, ‘What are you going to do with these 40,000 bullets?’ Gunpowder’s not so hard to make, you know? I was a bit shocked that I was able to do that.”

Robert Longo, Untitled (No Threat) (2018). Image courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Although Death Star 2018’s materials differ dramatically, Longo sees the sculpture as a natural extension of the work that has defined the latest stage of his decades-long practice, which has usually consisted of monumental charcoal drawings. New works of this type will be on view at the booths of both Metro Pictures and Thaddaeus Ropac.

Both bodies of work share more than the gravitas of current events. They also rely on meticulous construction and the overwhelming accumulation of details. Like the charcoal drawings, Longo says that Death Star 2018 is about “this idea of trying to slow things down, this kind of wave of images that we deal with on a daily basis.”

“It’s different than the click of a camera, a snapshot of a moment,” he says of his work. “What’s really important to me is that I choose these images, and I commit myself to these images for a chunk of my life.” He hopes this level of commitment will be powerful enough to stimulate viewers to re-examine their position on the issues at hand.

At the same time, Longo also makes clear that he did not create Death Star 2018 to be a tool for partisan evangelism or paternalistic finger-wagging. He defines gun violence as an “incredibly complicated” issue. “I can’t say I know the solution,” he says. “I don’t want to get up on the soapbox and point [at all gun owners] and say, ‘You guys are bad.’ But I want to at least try to make them question [their beliefs].”

The artist is also putting his money where his mouth is—and getting his galleries to follow suit. Upon the sale of Death Star 2018, 20 percent of net sales proceeds will go to Everytown for Gun Safety, a non-partisan nonprofit. The donation will be shared equally by Longo, Metro Pictures, and Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac.

Robert Longo, Untitled (Ferguson Police, August 13, 2014) (2014). © Robert Longo, The Broad Art Foundation. Photo courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.

Still, Longo hopes that Death Star 2018 can be its own change agent. “On one level, everyone talks about the negativity of the art fairs and art market,” he says. But “the art fairs are quite phenomenal in that 150,000 or 200,000 people go see these things. So you have the chance that [many] people actually see a lot of [important] work.”

If he has his way, the Messeplatz will not be the Death Star’s last stop before being enshrined in a permanent collection. When asked about the prospect of touring the work, Longo said the idea is currently being discussed.

The movement for gun control has received a major injection of energy through the efforts of teen survivors of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting and their peers around the country.

Longo hopes that artists can also play a role. “I want to believe that art has the capacity to help people understand things, or at least look at things a little bit differently,” he says.

“Everybody has these incredible biases,” Longo says, “and images reinforce biases” no matter where they occur. Still, “art maybe can mess with those biases, I hope.”