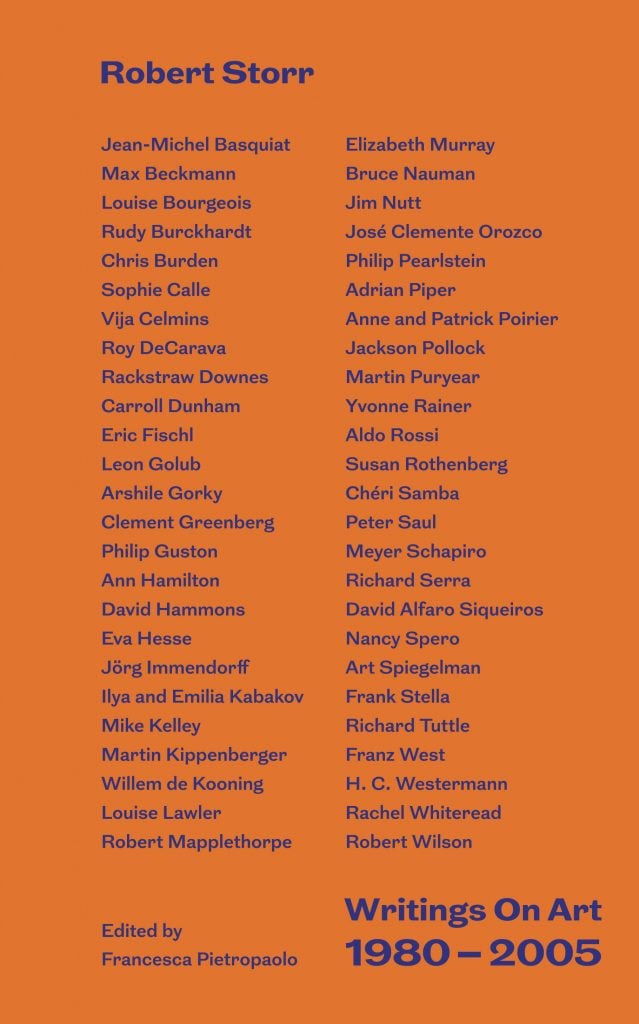

The bright orange cover of Robert Storr’s recently published collection of essays, Writings on Art 1980–2005, includes the names of 51 artists with seemingly little in common: Martin Puryear, Sophie Calle, Art Spiegelman, Rachel Whiteread, and on and on. What brings them together—perhaps the only thing that could—is the famously pluralist sensibility Storr has cultivated over his long career.

The book, which is the first in a two-volume set (the second will re-publish essays from 2005 onwards), also gives readers occasion to notice the ease with which Storr can move from generosity to bellicosity. On the one hand, he is a charitable writer who enjoys the pleasures of cerebral artists (Adrian Piper), sensualists (Philip Pearlstein), and “archaeologists” (Louise Lawler).

But he is quick to denounce anyone he sees as proscriptive (Clement Greenberg), self-indulgent (Frank Stella), or imperious towards public opinion (Richard Serra). Today, as many critics bite their tongues out of fear of popular reprisals, concerns about professional liability, or an outright lack of conviction, Storr is still taking shots at fellow writers and former friends like Peter Schjeldahl, whom Storr sees as a clear failure.

We spoke with Storr on the occasion of the new book about the inadequacy of art theory, why critics shouldn’t trust their own taste, and why modern art is not a relay race.

Let’s begin with the process of putting this book together. It covers 25 years of writings and quite a broad range of artists. What themes do you see running through?

One of the themes is the broad array. I’ve always felt that the writing of art history and art criticism in [the United States] has been tendentious and ideologically narrowing. So I thought the first thing to do was simply to set the precedent for writing that was sharp and focused, yet didn’t try to funnel everything into a big idea. I think there’s a point at which the record owes artists, but particularly art, some freedom from the controlling ideas of the critic.

There’s a quotation from Baudelaire that says: “Like all my friends, I have tried more than once to lock myself inside a system, so to pontificate as I liked. But a system is a kind of damnation that condemns us to perpetual backsliding: we are always having to invent another, and this is a cruel form of punishment.” I kept having to revise my theory, so rather than going through that experience over and over, I resolved not to have one.

In fact, a lot of these essays were written at the height of the “theory wars” of the 1980s and 1990s. Some critics said philosophy—and especially French philosophy—was essential for interpreting art, while others resisted that idea. Those battles seem to have subsided now, but what did we win or lose in those fights?

I was partially educated in France. I’m fluent in French and I read a lot of critical theory in French. I give it some credence overall. I am not anti-theory. But I don’t think we’re done with that particular intellectual or aesthetic development. I have so many students walking around mouthing statements that are simply handed down from the previous generation. The debates are not hot and heavy now, but their effects are deep and profound. And that’s precisely because the October crowd [of art historians] and others got away with hell.

Most of them didn’t know any art history, or not much, and they proceeded to blame and shame artists who didn’t fit their categories for reasons that were ostensibly about larger political realities that they had misunderstood. And they stayed very safely within the boundaries set by formalism in the 1960s and ’70s. What I do is just go out there and look and try to learn as much I can. That is a really simple proposition. That’s not a theory, it’s a practice.

Artworks at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Photo by Eduardo MunozAlvarez/VIEWpress/Getty Images.

There are critics who say it’s impossible not to have some theory, because you already have one, even if you don’t acknowledge it. There is always some implied lens through which you’re looking. How do you respond to that?

A lens is not a theory. A theory is a system of ideas; a lens is the recognition that you see things with certain kinds of biases. You cannot analyze things without focusing and filtering. I acknowledge that. But I also think that if one is a scrupulous writer, one can adjust lenses and choose them with care.

What’s the point of intellectual discourse if you can’t argue with yourself? One of the thinkers that has influenced me a lot is [the Russian literary critic] Mikhail Bakhtin, who talks about all literature being a conversation among the different dimensions of the writer’s personality. That’s what I do. I argue with myself. A lot of the arguments have to do with the value of what I was writing about.

What about taste? Do you think about that when you’re writing?

I think about it a lot and I am distrustful of it always, my own and other people’s. I think taste is essentially a conservative factor in art. Be that as it may, I do have things to which I’m alert, or things to which I respond, if you want to call that taste. That’s the point where my particular experience as a museum curator plays in, because I would have to argue for things that collectors found distasteful. Over and over, I had to say to them, “We’re here to judge the importance of works of art, not whether or not we want to live with it. Therefore, do not make your tastes or my taste the criteria for what goes into the museum. Make the importance of the work your criteria.”

Let’s talk about that. You worked at MoMA in New York for 12 years, starting in 1990. How did that play a role in these articles, some of which were written as catalogue essays? Do curators working inside institutions have a certain proximity to artworks that critics don’t?

Absolutely, and there’s a lot to be unpacked here. First of all, the Museum of Modern Art is not a museum. It’s a project. It has acquired and exhibited things as a result of this project. Knowing that tastes evolves, knowing that collections are disparate—that’s hugely important when you’re writing criticism because it reminds you that, in fact, there was no consensus. In the past, there were many competing forces. I used to say, as you go through [MoMA’s] collections, you should hear rumblings in the rooms because each one is devoted to one proposition about what modern art should be, and they all disagree with each other. Formalism, under Greenberg and under [former MoMA chief curator of painting and sculpture] Bill Rubin, tried to streamline it and say it was all part of the same thing. It is absolutely not.

I did a show at MoMA called “Modern Art Despite Modernism” that made the case that within the building are all the “also-rans” for being the definition [of modernism]. Some of them are very compelling and important. They’re not just the losers. They are the ones that didn’t win, but they’re not the ones that didn’t compete. That is the true history of modern art. It’s a debate about what modern art should be. The consensus that Greenberg keeps summoning is a fiction, and should not be treated as anything but. It’s also anti-democratic. It shuns some art and discourages independent looking at things that are puzzling. And the one thing all modern art should be is puzzling, right? [Greenberg] takes away from viewers that moment of not knowing, and tells them they should automatically know that this is better than that.

Clement Greenberg with his wife, Jenny. Photo by Hans Namuth/Condé Nast via Getty Images.

One thing that stands out about Greenberg is the certainty with which he issues his verdicts, and your essays are also written from a position of conviction. How do you prevent yourself from going too far?

Self-discipline. I have strong convictions, but I have absolutely no certainties. So I make an argument for something and I am convinced that the argument is good so far as it goes. But the important thing is not to push it past the point that it applies to what you’re talking about.

There’s a quote at the beginning of the catalogue for “Modern Art Despite Modernism” by [the Portuguese writer] Fernando Pessoa, who had different pseudonyms—heteronyms, he called them—in his writings. He had multiple personalities, and wrote both as a critic and as a poet, and each poet and critic had a different identity. The quote is: “One God is born. Others die. Truth/Did not come or go. Error changed.”

Pessoa is a model of a pluralistic individual performing at a very high level. And if you think of each “ism” as the assertion of an interesting proposition and also the birth of a new error, you’re better off than if you think it is the truth that supersedes previous truths.

Let’s talk more about museums. They’re in the midst of a reckoning right now, having to accommodate concerns about the canon and sensitivities around the artists and art they show—I’m sort of dancing around the postponement of the Philip Guston show at the National Gallery of Art. What role should institutions play in navigating these concerns?

They should be the forum for those debates. They should not be trying to pussyfoot with them, they should actually be the place where they take place. I think museums are ideal for that, and I think the more noise, the better. I know people think that’s naive, but don’t tell me I’m naive having worked for as long as I did at MoMA. I know what the restraints on museums are. I know trustees, I know the power of ideologies. Gimme a break. The speed with which the curators at the National Gallery caved is not an indication of whether it’s possible, but whether they have backbone and guts, whether they are willing to risk their positions. [Curator] Mark Godfrey at the Tate stood up for his beliefs, and he got clobbered. But he stood up for them and that’s to his credit.

A visitor looks at Philip Guston’s Riding Around in the Falkenberg in Hamburg. Photo by Bodo Marks/picture alliance via Getty Images.

Did you see Peter Schjeldahl’s take on the whole matter? He basically second guesses the art-world consensus that the postponement was unwarranted.

Peter was the person who introduced me to professional art writing, and he was a very good friend for a long time, and then he became a very bad friend later. I have nothing but disappointment in Peter’s behavior in the last 20 years. He has retreated into an ever smaller, more taste-based, more capricious definition of what is legitimate. And he’s also turned himself into a kind of a libertarian. He has politics—although he says he doesn’t—and he believes basically that art is for those who are lucky enough to have some. He was all set to sell the collection in Detroit for idiotic reasons that I think even Ted Cruz would be embarrassed by. That’s what Peter does. He makes extreme statements, gets caught up in them, apologizes, and thinks all is forgotten.

The point is, he has no binding principles of conduct. I’m not talking about ideological or aesthetic ones. He has no sense of professional conduct. He excuses every excess that allows him to write a flashy article and I think that’s diminished his criticism massively. He was really good at drawing unexpected connections and he has an enormously gifted way with words. But Peter’s problem was that he started being declarative. He was saying that he was the most daring and most free individual in the game. He wasn’t free at all. And he couldn’t acknowledge the ways in which he wasn’t free. He is afraid of ideas to the point that he can’t be good critic.

Speaking of politics, you’ve said before that you’re a lapsed Marxist. Are you reassessing any of your old politics lately?

I’ve thought about it a great deal. Part of me says, “Rob, you really should have gone hardcore and just become a militant.” But what beset me in the 1970s, when I was very close to making that decision, was that I had friends who were so dogmatic and so disparaging of art and so cruel to me personally, that I just walked away from it. I felt that heat and I’ve seen those people become ideological and I don’t want to have anything to do with it. I also distrust academic Marxists because they have never done any real politics at all, so they don’t know that danger. I don’t believe in lining up the oligarchy along a wall and shooting them. I don’t believe in the state taking everything and doling it out to whomever. I am a failed Marxist in that sense, too: I am not willing to do the extreme things that certain branches of Marxism think is necessary. I just won’t do it.

All things considered, would you say you feel politically optimistic right now, or pessimistic?

You know the formula of [the Italian Marxist thinker] Antonio Gramsci? “Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” I think things are very dire. I did not anticipate the degree to which the world was fragile, and Trump basically provided the evidence that it was. Somebody else is going to come along and analyze the scraps and put them together in a horrifying way. But I don’t think that means our window is closed. One of the things we have to do is stop the ideological “I’m right and you’re wrong” discussions. We have to try to figure out how to build coalitions. Those are the only ways to save this country, because [the US] was in fact a coalition from the outset. Most positive movements in political history have been coalitions, not ideologically pure tendencies.