Art World

Former Robocop Actor Peter Weller on How an Epiphany at a Picasso Show Motivated Him to Become an Art Historian

Weller is giving a lecture in Detroit this weekend on the "Crisis of Beauty."

Weller is giving a lecture in Detroit this weekend on the "Crisis of Beauty."

Taylor Dafoe

Peter Weller, the actor who once played Robocop, is returning to Detroit this weekend. Although he won’t be fighting crime in Motor City, he will be fighting a battle of a different kind—against the censorship and destruction of art.

After playing Robocop and the eponymous Buckaroos in the 1984 sci-fi cult favorite The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension, Weller returned to academia. In 2004 he enrolled at Syracuse University, earning a Master’s degree in Roman and Renaissance Art, then he earned his PhD in Italian Renaissance art history at UCLA in 2013. These days, he splits his time between acting, directing, producing, and giving lectures on the Renaissance.

This weekend, Weller will deliver the keynote speech, on “The Crisis of Beauty,” at the opening night of Culture Lab Detroit, an annual symposium that brings together artists and thinkers. Ahead of Culture Lab, Weller spoke with artnet News about what this crisis entails, how he transitioned from acting to art history, and the kind of work he personally collects today.

Peter Weller in The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (1984).

When did you first become interested in art?

My mother, who was a musician, was always trying to get me interested in art. I loved movies, of course, but I didn’t make the connection to art at first, which was ridiculous, because it’s all related. It’s all visual. It’s all endemic—one thing bleeds into another. In my 20s, I was living with Ali MacGraw, who’s still a great friend. Most of us know Ali MacGraw as the movie star in the 1960s and ‘70s, but what many don’t know is that she was working on a Master’s degree in design at Wellesley. Diana Vreeland, the editor at Vogue, used to pick a “girl of the year.” Sylvia Plath was Vreeland’s girl one year. So was Ali.

I started hanging out with Ali after this movie. We were living in New York and, at the time, every evening was a cultural hit. You would think that Ali would be hanging out with actresses, but her friends were writers and artists: Martha Graham, Alvin Ailey, Andy Warhol, Mark Rothko, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, Betty Friedan—on and on! That was her real life in New York. And I was the caboose at the end of the train, because many of these people were heroes to me. Though, at the time, I didn’t really know who the artists were, because I wasn’t hip to contemporary art.

So I called my hipster mother, and then I said, “Ma, every night I’m out with these people, I don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to say.” And my mother, a very wild and fun woman, said, “Well, just shut up and listen!” So that’s what I did. As a young guy, you always want to make a contribution, but hanging out with Calvin Klein, Giorgio Armani, Richard Avedon, Herb Ritts—what kind of a contribution are you going to make? It was a plunge into contemporary art, in all of its facets.

Peter Weller and Ali MacGraw in Just Tell Me What You Want (1980). Courtesy of Warner Bros.

When did you start working your way back through art history to the Renaissance?

Well, when Picasso’s Guernica was going back to Spain, MoMA had a five-floor retrospective of his work—the largest one ever done. And Ali, with her cachet at MoMA, took me by the hand and we had a private viewing at MoMA. She took me from Picasso’s original figurative art, through his cubist period, and so on.

Renaissance art is a turn in the middle ages—it really is in the middle ages—that had to do with the rediscovery of the values of antiquity through writing. It’s the humanism, it’s the plays of Cicero, and it goes on and on and on. It’s military history, it’s political history, it’s intellectual history. So I go, “Wow, where do you go to study this?”

When I got to see [the Picasso], the lights went off! I started to see the connective tissue of visual art. I could say, “Wow, the guy was really trained as a draughtsman in figurative art. Wow, he got on board with 20th-century ideas,” and on and on. And if you could walk your way through Picasso, you could walk your way through Piet Mondrian, who started the same way as a figurative drawer, and then goes through to abstraction. Then you could walk your way back through a number of great artists in time. But when you get back to the Renaissance, it’s not just figurative art anymore.

Subsequently, this is the second stage, I was in this film festival in Japan with Mike Medavoy, a great friend, Jeanne Moreau, one of the seminal post-modern actresses, and Vittorio Storaro—if anyone changed color photography it was Vittorio. Vittorio started as this really expressionist cinematographer with Dario Argento and he got to monkey with color forms. I asked him, “Who’s your favorite painter?” Vittorio said to me, have you been to see Giotto? And of course, at that time I didn’t even know who Giotto was. I said, “I don’t know,” and he, with his Versace scarf around his neck, said [mimicking Italian accent], “Well, Peter, we cannot speak about art.” And he walked away! I cornered him, and said, “C’mon, what do you mean we can’t speak about art?” And he just said, If you don’t go see Giotto, if you do not see the very first iconic art that moved into narrative and depth and space and time and feeling—just like a movie—then you have no context. Without the context, you have no sense of the tissue, of the lifeblood. You just have opinions.”

So I got back to see Giotto. It was back in the day when you could smoke a cigar in the place and have a cappuccino in the dead of winter. And holy cow! You see Giotto’s renderings of the Virgin Mary and Jesus in a chapel that’s no bigger than a small library! And it’s panel after panel after panel of game-changing narrative, man. And that chapel, by the way, figures into my dissertation.

A detail of Giotto’s cycle of frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

What was your dissertation about?

The seminal renaissance guy, who you can’t attack in Florence, is Leon Battista Alberti. He’s who brought Latin to renaissance art, among many other accomplishments. He also wrote the first treatise on painting in Latin, De pictura—it was a very important text. But there’s nothing in that book that refers to any contemporaries of his that influenced him. The only person he mentions is Giotto, everybody else is antique. Reading it, I said, “Bullshit, this guy did not write this by just looking at antique art. He had to have been looking at art that was contemporary to him all along.” I said, I don’t think this guy just saw Massacio, got to Florence, saw Massacio and wrote this book. I think he saw Massacio in Rome, Donatello in Rome, I think he traveled to the north, and saw all of the northern guys—Van Eyck and so on. And my advisors said, of course he did. But no one’s written that yet, so why don’t you write it. So I began looking at who his contemporary sources might have been.

If you go to Florence, and you suggest that Leon Battista Alberti or any of the Ninja Turtles were ever influenced by anything outside of Florence, they want to hang you! Because as far as Florence is concerned, the renaissance began, flourished, and ended there. They have such arrogance about it. And the Florentine art historians are the same. There are great historians that study outside of there, of course—in Naples, Rome, Parma, Milan, Venice, and you’ll get support from those people, but you will not get it in Florence. And so I’m looking around and reading, and I began thinking to myself that Padua is really the beginning of all of this—because Padua was taken over by Venice in 1400, and Venice never really got along with the papacy and the hammering of the church, so they were very libertarian in their beliefs.

In Padua, which was one of the great centers of research and a vibrant university town, they just had a groove. So I wrote my dissertation on the early sources that informed Leon Battista Alberti’s De pictura. It was an argument that he did not go to Florence, he dedicated the book to Florence, but he did not write that book in Florence.

Leon Battista Alberti’s tomb in Florence. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Did you get any negative feedback after publishing it? Any flack from the die-hard Florentines?

I got some verbal feedback from some Florentines! Specifically on the gendering of Donatello’s bronze David. The great art historian John Pope-Hennessy wrote this thing in the 1970s saying that we’re not looking at this statue right, that you can’t gender it as gay. You can’t even classify it as homoerotic. I started looking at all this and I took pictures. From straight on you see this elongated torso, but then from the other angle, you can see John Pope-Hennessy’s argument. It’s completely punk! Put it on a Mardi-Gras float and it’s totally camp! So I presented that argument at Brooklyn College, and man did people come out of the woodwork on that.

Actor Peter Weller and Sheri Stowe at the premier of Star Trek Into Darkness. Photo by Frazer Harrison/Getty Images.

I read that you presented your dissertation the same day of the Star Trek premiere. What was that day like?

It’s interesting how it came about. I got this big grant from UCLA, and at the time I was doing Star Trek: Into Darkness, and I was also directing the TV show Longmire—it’s one of my favorite shows ever. One of the coolest moments in my life was when I got this call from UCLA and they said, ‘we have to see one hour of your dissertation, to see where our money went’—you know, to make sure that I didn’t go buy a Corvette or something. So I’m shooting Star Trek, and that morning I had to prep Longmire. I get on a plane to LA, I call Paramount to pick me up and drive me to UCLA. I present what my wife had suggested I present, which was how I got into this dissertation, using images, rather than boring everybody shitless. Then I went that night to the premiere.

The talk you’re giving at Culture Lab Detroit tackles the “crisis of beauty.” What does that mean to you?

I think about the crisis of beauty in two contexts. You could take the context of the threat of what mankind’s greed or negligence does to beauty, such as urban issues. And I’m going to show pictures of what New York and Detroit used to look like. But then we’ve got the other crisis of beauty: Who gets to determine what is beautiful? And the history of art and beauty is littered throughout history, right up to when Rudy Giuliani proclaimed Chris Ofili’s painting of the Virgin Mary as horrible pornography because he deemed it ugly (and because he is ignorant to Ofili’s background). That’s insanity, man. It’s fascism. I mean, it’s an amazing anomaly, that this guy can order New York to be “cleaned,” can declare that all these pre-war buildings can’t be torn down, then turn around proclaim a major piece of art as trash and stop the public from seeing it. That’s what I term the crisis of beauty now—censorship.

Caravaggio, The Madonna and Child with St. Anne (Dei Palafrenieri) (ca. 1605-6). Courtesy of Wikimedia.

And those questions don’t just pertain to contemporary art. Last year, for example, there were accusations that a museum censored the pre-Raphaelite painting Hylas and the Nymphs (1869), and we’ve seen Facebook continually censor works by Courbet and Peter Paul Rubens.

Absolutely. There’s a great example of a painting by Caravaggio in the Galleria Borghese called The Madonna and Child with St. Anne (Dei Palafrenieri). It was commissioned for the Archconfraternity, tied to Saint Peter’s, and he’s depicted Mary with her breasts spilling out of her dress. The baby Jesus is a young child, about six years old. The Fraternity called it pornographic and said, “This is hideous, we’re not putting this in our chapel.” Luckily, Cardinal Scipione Borghese, a great art collector and a patron of Bernini, took it. And thank God because now we get to see it today. It’s gorgeous. But you can see the crisis of beauty in 1608.

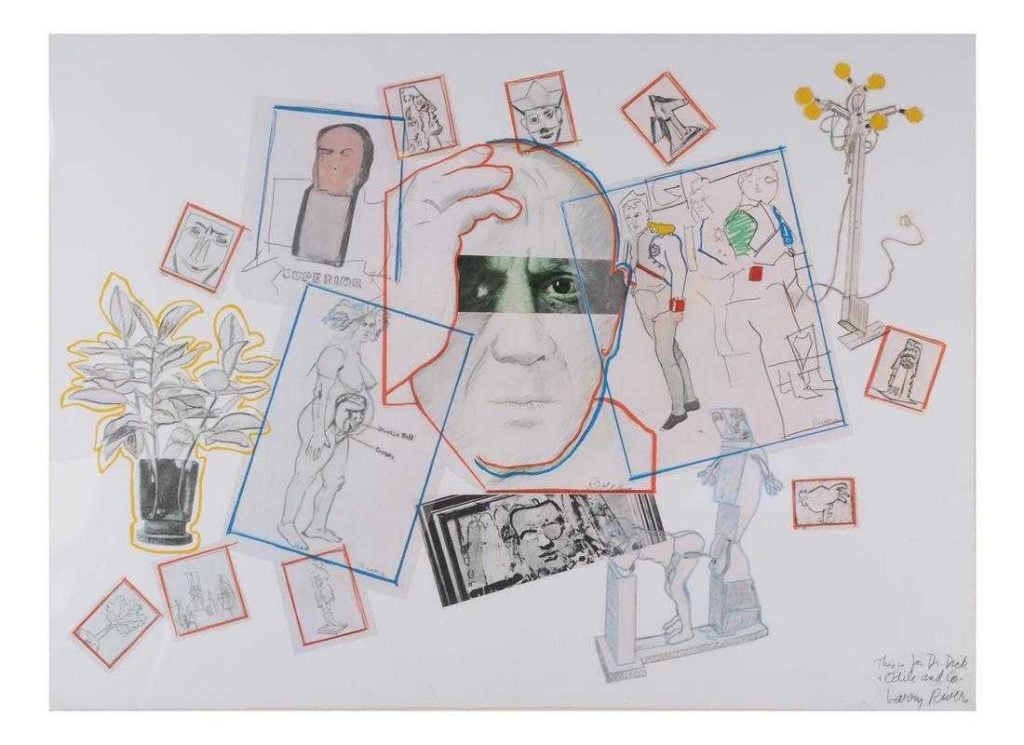

Larry Rivers, Untitled from Homage to Picasso (Hommage à Picasso) (1974). Courtesy of Peter Weller.

You’ve mentioned that you’re a pretty active art collector. Which artists do you have in your collection?

The thing is that art can send you into chapter 11 in no time. As a matter of fact, I just got an invoice for something I Just bought at auction—it was a Larry Rivers. I chased a particular painting of his for years. Larry is a really good tenor sax player, and he did a really great collage relief of Charlie Parker’s hands on the saxophone. I was chasing it, but couldn’t afford it. Then Larry found out I was interested in it and, I don’t know what he did, but he made it so that I could buy it.

I also own a great Lee Krasner. She was the first woman whose work MoMA acquired. It’s a mixed-media work on board. I also own a Hans Hoffman. He was the first abstractionist I ever loved. And my wife hates it! She says, “Can’t you move this?” I tell her, “It’s like he’s doing a genetic code here,” and she just says, “I don’t give a shit what he’s trying to do.”