Billionaire collector Ronald Lauder is giving the public a rare opportunity to view his sweeping art collection. To celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Neue Galerie, his Upper East Side museum for Austrian and German art, he is putting some 500 of his own works on display.

Lauder, 78, is the youngest of two sons of the late eponymous cosmetics tycoon Estée Lauder. Over the years, he has promised gifts to other museums, including 91 pieces of European arms and armor to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in December 2020. Lauder’s brother Leonard, 89, is also a top collector. (Per the 2022 Forbes billionaire list, Ronald, number 552, has $5 billion, while Leonard, number 65, has $23.1 billion.)

Both have self-described eclectic tastes. While Leonard has focused on postcards, posters, and Cubist art (the latter comprising a promised gift to the Met worth a reported $1 billion), Ronald’s collection is even more wide-ranging.

A decade ago, for Neue Galerie’s 10th birthday, the museum hosted an exhibition of works he owned spanning the third century BCE to the 20th century. The current show—titled, in unvarnished fashion, “The Ronald S. Lauder Collection” (through February 13)—focuses on other elements, including ancient Greek and Roman sculpture and 13th and 14th century Italian painting. There are plenty of quirky inclusions as well, from a selection of memorabilia from Casablanca (Lauder’s favorite film) to cabinets filled with ivory. (His collection of cars and fighter planes, on the other hand, is not included.)

A view of the Neue Galerie. Photo by Christina Horsten/picture alliance via Getty Images

Through a spokesperson, Lauder agreed only to an email interview, and he responded to some of the questions Artnet News posed and declined to answer others. We asked him—in the style of BBC Radio’s Desert Island Discs—to select a few favorite works from his collection, which he would take with him to a deserted island. Lauder said he falls in love with each acquisition.

“They are like my children—I love them each equally but in different ways,” he wrote. “I would have to get a big steamer trunk to bring as much as I could with me.”

In 2007, Lauder told The New Yorker that his mother had a Schiele painting on a dining room wall which was “bought at his urging.” Ronald, whom the collecting bug bit first, “would badger his brother, Leonard… to get involved.” He added, “I just loved the idea of being an art collector.”

Lauder did not respond to questions about his earliest acquisitions, but according to the 475-page exhibition catalogue, they seem to have been 16th century German or Flemish pictures. Among them was Quinten Massys’s An Old Man (c. 1513), purchased from “the venerable dealership Rosenberg and Stiebel, at a time when no authoritative monograph had yet been written on the artist.”

Bernardo Daddi, Madonna and Child with Four Angels (1348). Courtesy of the Neue Galerie.

Lauder told the New Yorker he would buy catalogues raisonnés, and he found the market valued Monets and Manets over German art right after World War II. He bought some of his best work from Upper West Side apartment walls, he told the magazine: “I would go through every book, page by page, and my favorite two words in the book were ‘private collection.’”

Lauder describes his go-to collecting principle the “Oh My God Formula.” An “Oh” is not that important; an “Oh My” is not the artist’s best; and an “Oh My God” is “one of the artist’s truly great pieces.” Lauder writes in the catalogue: “Those are the pieces, the Oh My God works of art, that I have collected over the course of 65 years.”

Has Lauder ever followed his “Oh My God” gut feeling contrary to the advice of consulted experts? “I tend to have an immediate reaction to a work upon first seeing it,” he told Artnet News. “After more than 60 years of collecting, I know what I like and have cultivated a deep knowledge within the areas of art history that interest me most. Of course, there is always deeper research that is done as I assess a potential acquisition and think about it within the broader context of the artist’s oeuvre or that period of creativity.”

Lauder has built the collection with the help of Elizabeth Szancer, who edited the show’s catalogue, as well as additional staff researchers.

Installation view of “The Ronald S. Lauder Collection” on view at Neue Galerie New York. Photo: Hulya Kolabas, courtesy of Neue Galerie New

York.

He believes that “the range of my collecting interests and connoisseurship is unique,” insofar as he does not quarantine his areas of focus to just one or two domains, as many collectors do. “My collection spans eras and ages. It is not driven by the market trends, but by my own aesthetic interests and passions, which I think results in a collection that is very personal,” he said.

Lauder claims that he has never been very interested in the art market, and has never allowed it to dictate his collecting. “I’ve tended to run against the herd,” he said. “All art was contemporary at one time, informed by the social and political perspectives of the moment in which it was created. My passion for history, for gaining deeper understanding of another place and time, has fueled my interest in collecting the masters, from antiquity to the modern era.”

To Lauder, Austrian and German Expressionism appealed for its aim not to transcribe reality objectively, but to capture artists’ inner worlds. “It is perhaps this reason I have always found the work of these artists so compelling,” he told us. “They are highly personal, unexpected, and often challenging—encouraging the viewer not only to look but to feel.”

Yet over the past decade, sensing a dearth of “Oh My God” pieces in that area, he took what he describes in the catalogue an “important detour.” Recent acquisitions have ranged from Spartan helmets (500–400 BCE) and first and second centuries CE Trojan and Roman sculpture to 13th to 15th century Italian gold-ground paintings to small-scale 16th- to 18th-century gold objects from Kunstkammers (so-called curiosity cabinets).

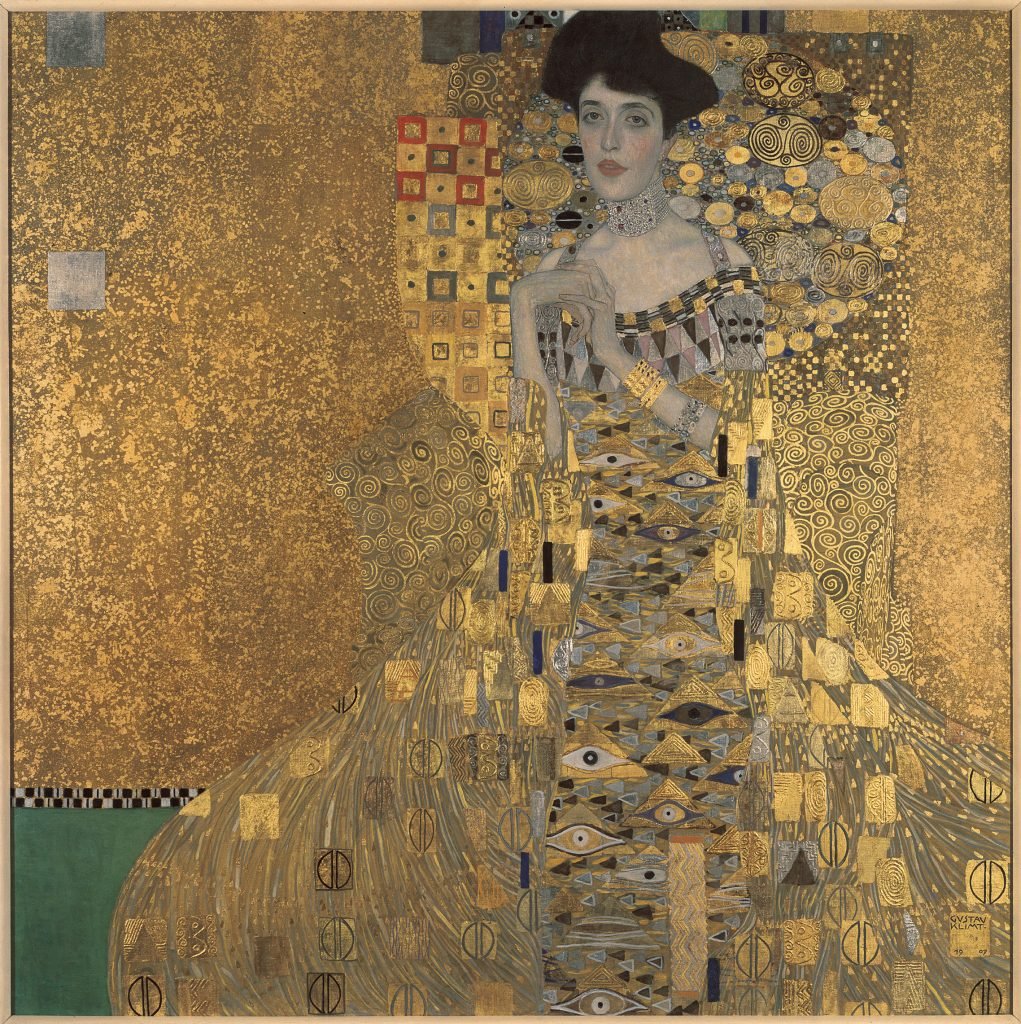

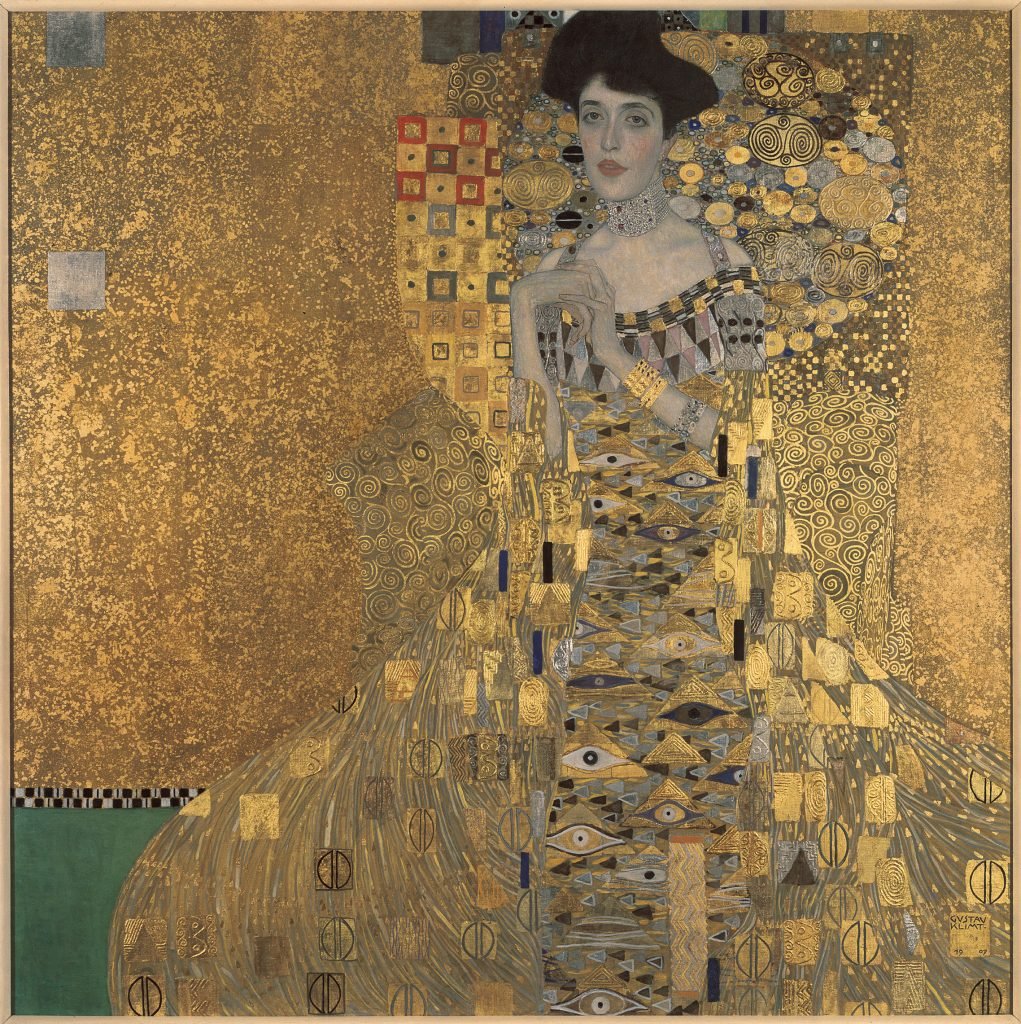

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907). Courtesy of the Neue Galerie.

Lauder’s most famous work is surely Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), which, as Artnet News reported, was part of one of history’s largest cases of Nazi-looted art restitution. Among the works from Lauder’s collection on display—many of which have never been seen, according to the museum—are a c. 1200 walrus ivory chess piece from the Lewis Chess Hoard and The Virgin Mary Nursing the Christ Child (late 15th century) by Hans Memling. The exhibit displays the art alongside furniture from Lauder’s homes.

Lauder serves as president of the World Jewish Congress, which bills itself as the “Diplomatic Arm of the Jewish People” and is involved in many Jewish philanthropic and activist causes. (He is also a prominent donor to Republican candidates.) But his identity as a cultural Jew does not impact his collecting, he said; he is drawn not to Judaica but to objects with “cultural and art historical significance,” as well as “the beauty and craftsmanship of the object itself.”

Installation view of “The Ronald S. Lauder Collection” on view at Neue Galerie New York. Photo: Hulya Kolabas, courtesy of Neue Galerie New York.

Looking ahead, Lauder kept his plans for his collection’s future close to the vest. “Supporting museums and cultural institutions has been a key focus of mine. I consider myself a temporary guardian of the works in my collection, which belong ultimately to the public,” he said.

“It is also why I have very strategically thought about the future of my collection and have begun making major promised gifts that ensures these works can stay together within the public realm,” he added. According to a Neue Galerie spokesperson, there have been other, smaller promised gifts beyond that of the arms and armor to the Met, but “he has not shared more than that at this point.”