People

Rudolf Zwirner Helped Invent Today’s Art Market. Now He Thinks the Pandemic Could Bring the Business to a New Golden Age

The father of David Zwirner is a pivotal figure in the history of the market.

The father of David Zwirner is a pivotal figure in the history of the market.

Kate Brown

It’s hard to sum up a career like Rudolf Zwirner’s. The 87-year-old German art dealer played a decisive role in shaping the art market as we know it today, founding the first fair, what is today called Art Cologne; He also pioneered art dealing in a post-World War II Germany that was in ruins before rearing a son, David Zwirner, whose art empire is now among the most important in the world.

The art business wasn’t easy when Rudolf Zwirner started out. He struggled to attract art collectors in a country that had once been a cultural force, but which was now in rubble. Still, the dealer, who was born in 1932 to a well-to-do family, started to see a landscape of possibility.

He established his own art gallery in 1959, bringing American Pop artists like Andy Warhol across the water. He championed foreign artists like Cy Twombly, Panayiotis Vassilakis, and Daniel Spoerri—and homegrown talents like Joseph Beuys, who staged one of his first actions in Zwirner’s Cologne branch. He organized the second-ever edition of Documenta in 1959. And then, feeling that the art market had more potential in its store, he founded an art fair. The model was quickly copied by Ernst Beyeler, who co-created Art Basel in 1970.

On the occasion of Zwirner’s new autobiography, Give Me the Now, he spoke with us from his home in Berlin about his son and grandson, the business landscape for art in post-War Germany, and what dealers these days should be focusing on.

David, Lucas, and Rudolf Zwirner with Sylvester (2001) by Richard Serra, Glenstone, Potomac, Maryland, 2018. Courtesy David Zwirner Books.

Let’s start at the beginning. What led you to open your art gallery and, eventually, the fair that became Art Cologne?

After the Second World War, it was very empty in Germany. There were just about ten or 12 dealers after all the Jewish dealers had to leave the country—and most of the great dealers were Jewish.

At the end of the war, there were fantastic people who came back into politics—really fabulous people who spent years and years away during the war. They were really interested in bringing culture, in a democratic way, into the public. These people were really democratic and they suffered under Hitler—like Kurt Hackenberg, who was in charge of cultural affairs in Cologne. He was such an inventive figure. Without him, there would have been no way to organize an art fair [like Kunstmarket Köln, which became Art Cologne]. Looking back, I was really happy to spend my first years in art in a democratic city like Cologne.

There was a kind of chance for me to start with no money with contemporary art. And when we started what became Art Cologne, there were just six of us who sold contemporary art ,so it was really a risk. There was very little interest in contemporary art at that time. Now, there are 3,000 galleries in Germany that focus on it.

Does that number surprise you?

It surprises me a lot. The highest price we could get for contemporary art was 10,000 Deutsche Marks [about €22,000 when considering inflation]. It was really shocking when the prices continued going up with no end. I had 12 collectors in Germany—there were five in Cologne, two in Darmstadt-Streuer, and so on. But this is all.

Now, your son David Zwirner likely has thousands of collectors.

Yes, thousands!

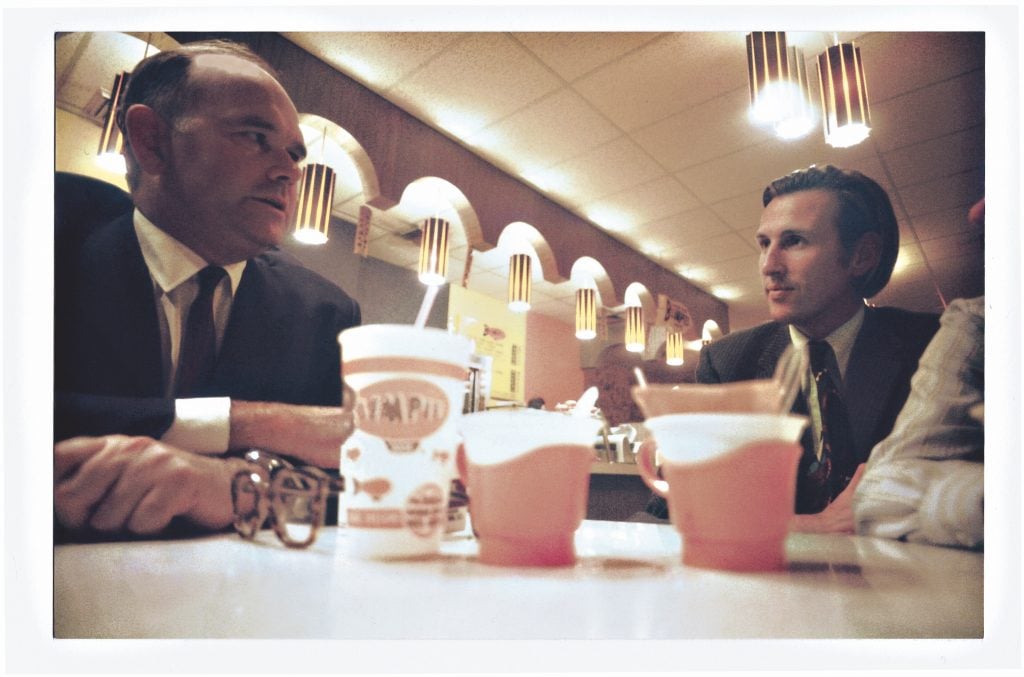

Visitors at the first Art Cologne, the first art fair. Photo by Peter Fischer.

What was it like to see Modern art for the first time after the war?

It was only in 1955 at Documenta that I saw, for the first time in my life, contemporary art. I suffered in a way from this, because [art dealer] Ernst Beyeler, who was a little bit older than me and in Switzerland, saw within 10 to 15 years in Basel everything that became important for him later: Picassos and Klees, and so on. But I discovered contemporary art only in 1955. It was much too late for education. Before that, I had postcards with reproductions from the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. I never saw anything like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and this was a big difference to everyone who was dealing in the US.

It is still amazing to me that only 12 years [the Nazis were in power from 1933 until 1945] made it possible that we did not see anything from entire periods—from the 1930s, the ’20s. We saw no Mondrian—nothing! It is crazy. You cannot understand.

What happened when you saw works like that for the first time?

When I showed up at the first Documenta, as a student in Freiburg who was interested in art, I came into the buildings of the Fridericianum, which was still a ruin. I saw Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Picasso, and Matisse. It was a shock for me. I decided to change my life. I decided not to continue my studies and went right into the art world.

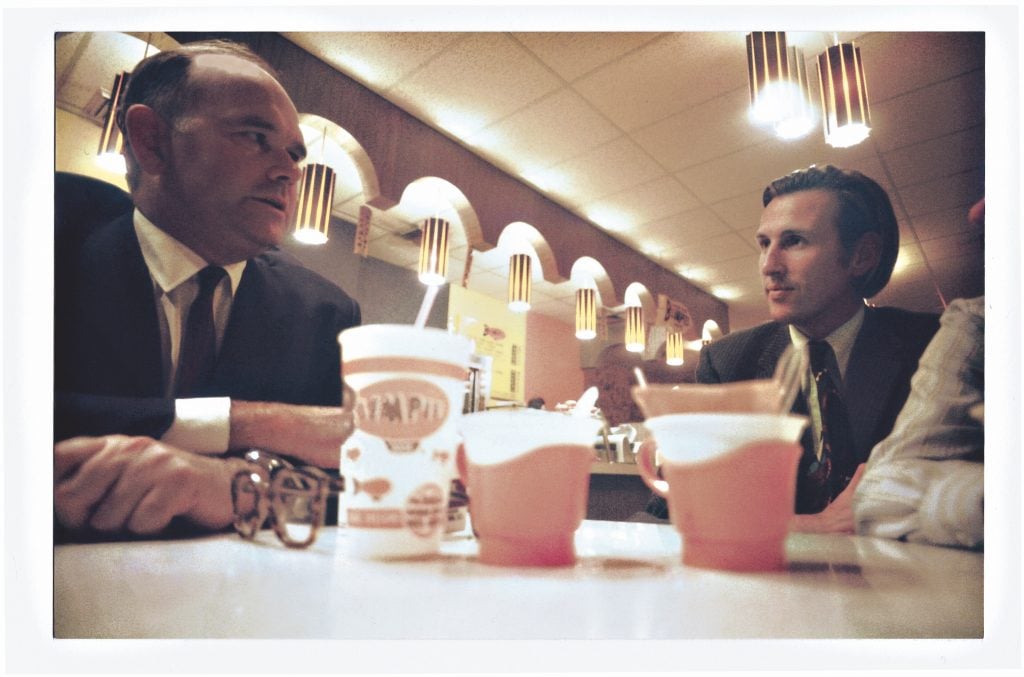

Rudolf Zwirner boiling an egg during the seven-minute opening of Daniel Spoerri’s exhibition at Galerie Rudolf Zwirner, Cologne, on September 12, 1963. Photo: ZADIK, Cologne/Jaschinski- Dreger. Courtesy David Zwirner Books.

You just spoke about Ernst Beyeler, the preeminent Swiss art dealer who co-founded Art Basel. He was a competitor of yours throughout your life.

He was a real competitor. I started the first art fair and Beyeler saw this and started his art fair with much more success in Switzerland. Don’t forget, Germany was a Nazi country, so all the Jewish collectors never, ever wanted to step foot in here. They were happy to go to Basel, where they spoke German. And from Basel, you can see the Rhine river. But they did not want to go into this country, with all the murders and so on. It was a real problem.

Especially when the [Holocaust architect Adolf] Eichmann [trial] occurred and everybody knew more about what really happened, all the German artists who were shown in New York or abroad did not get any shows anymore. In 1963, the [Frankfurt-Auschwitz] trial started in Frankfurt, and contracts were canceled with German artists. Israel or New York would not show German artists. When I tried to convince [art dealer Arne] Glimcher at Pace gallery to show early works from Baselitz. He said he liked the work, but that if he ever showed Baselitz, he’d lose all his clients and that it would be ruin of his business. This was in the early 1960s. It was much much later, when Glimcher showed Baselitz for the first time.

It changed only much later when [German artist] Anselm Kiefer was shown [in 1983] at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. From this moment on, Jewish collectors would come to the gallery. Jewish collectors were buying German art.

You shouldn’t forget that the main collectors are Jewish. They were the most important dealers and collectors in Germany with all the important contemporary collections in the 1920s. In the US, all the important galleries are Jewish. This is fantastic. But it is strange that nobody talks about this.

When you started your gallery in 1959, there were very few others. It was fruitful, but also a struggle at times. This pandemic has brought on a serious sense of precariousness for art dealers. One could, unfortunately, imagine a future with fewer dealers in it. Do you think this could become a reality?

This is a very important question. Dealers must spend more time in the city where they have their gallery. The virtual art business will be absolutely necessary in the future because they can reach everybody in the world, but they have to invent something to bring people back into their spaces. They must do more than just show [art]—they must talk to critics, host discussions. There is a chance to bring people back.

In my early times, when no one showed up to an opening, we had so-called Happenings. I would host a concert with Nam June Paik and Charlotte Moorman. There was always something going on besides the paintings or sculptures. And I had to do this because nobody showed up! I was alone. Galleries need to do that again. They were all so busy running to the next fair. Next fair, next fair… empty galleries.

All of it was too much. This is the only good thing about the pandemic. At Art Basel, you had a pre-ticket, and a pre-pre-ticket. People were rushing to be the first to buy for investment. It was really obscene. I think this is over. There will be a few art fairs that will happen, but to have an art fair in each city—it is crazy.

On top of that, only the big galleries could afford to attend 30 fairs. And, in doing so, these galleries lost contact with their home cities because they were either at the art fair or preparing for the fair. The paintings they had in the gallery were reserved for the art fair. That is crazy. I’m sure the quality of the art will be better in the next few years.

Works by Yayoi Kusama are on display at David Zwirner Gallery’s booth at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2013. Photo: Mireya Acierto/Getty Images.

Can you elaborate on why you think it will catalyze better art, specifically?

The artists will have time. I remember when we used to call artists and ask for two or three paintings because we needed something for Art Basel, or because we needed something for Art Cologne. Crazy! We were happy to get a second and third-rate Baselitz just to sell a Baselitz at the fair. It was too big, too quick, and too much. One also had to bring paintings with a high price to pay the bill for the fair—a decent fair booth will cost €100,000 or €200,000. That is too much.

In our reporting, we have been hearing from a lot of dealers that they actually saved money this year because of this absence of fair expenses.

David told me that this was the best year. “How could it be?” he said to me. “Because I didn’t spend all these millions on art fairs.” Unfortunately, he had to cut people who were responsible for these fairs around the world because there were none. So while the turnover went down, the profit in the end turned out better. Can you imagine?

With the pandemic is a real chance to start something new, while keeping on top of this virtual business—but they have to do it much better. One cannot just to show inventory. Describe the major work, send texts around the major work, and do not send it to everybody. Send it people who will be interested on a personal level—it needs to be personal even if it is virtual. Very few people can do this. David and his crew are on top because they really explain and invite you in.

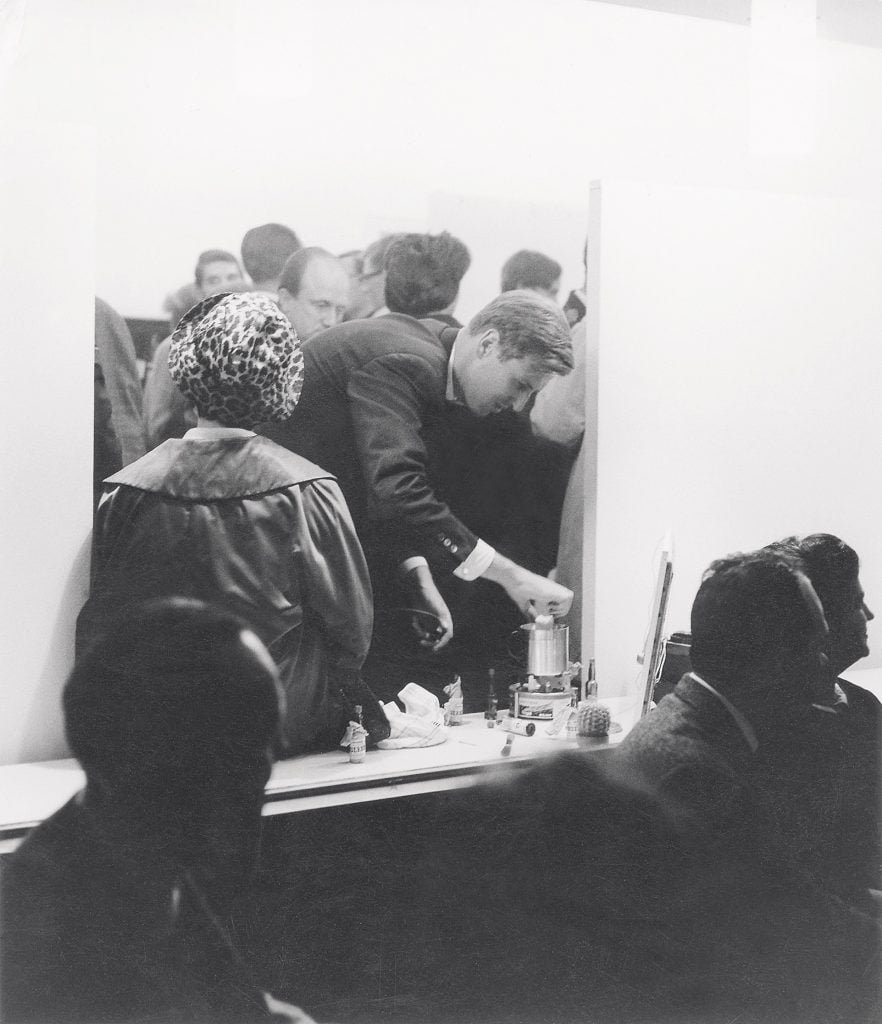

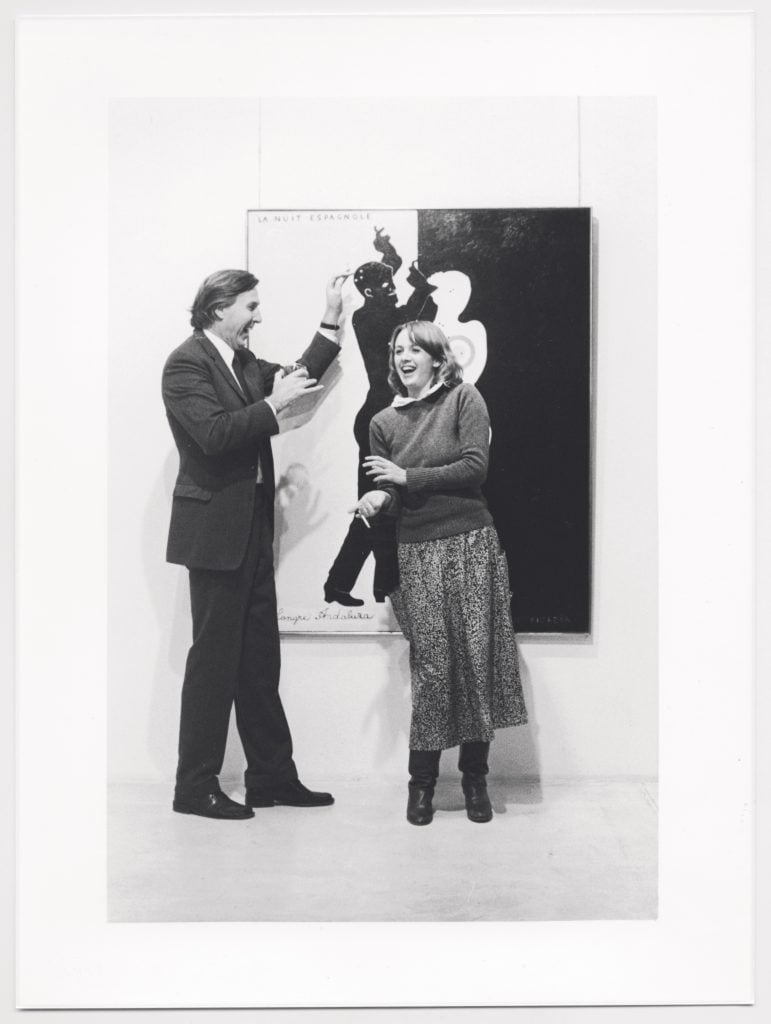

Rudolf and Ursula Zwirner with Francis Picabia’s La nuit espagnole (1922). Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln.

In your book, you describe a stagnation in the art scene and market of Germany in the 1960s. Do you think the art market in Germany has stagnated again?

Germany is a rich country, and yet the art market is close to zero. That is mainly because taxes are too high—it is almost 25 to 33 percent on top. It is much less expensive to buy a painting in Switzerland or somewhere else in the world, so collectors prefer to buy somewhere abroad. It is cheaper to see a painting in Germany and then buy it in Switzerland. I know very few collectors who are here buying in Germany. Even after the pandemic, we have to find a way that we can compare our prices with colleagues in London, New York, and Switzerland. This is a big problem.

One thing I can also still not understand is that there are not enough young major collectors. People are very rich in Germany. But David tells me he can never sell a painting above €100,000 in Germany at an art fair. Going back to galleries in New York, prices start around €100,000. All the high prices are fetched in New York, Hong Kong, and wherever. This is a really big problem—good artists in Germany have to find a dealer in New York or Hong Kong.

It’s interesting to hear that because David Zwirner is often in attendance at Art Cologne.

Yes, but not to sell, more so to buy what I sold there 20 or 30 years ago, which he can then bring to the US or Hong Kong.

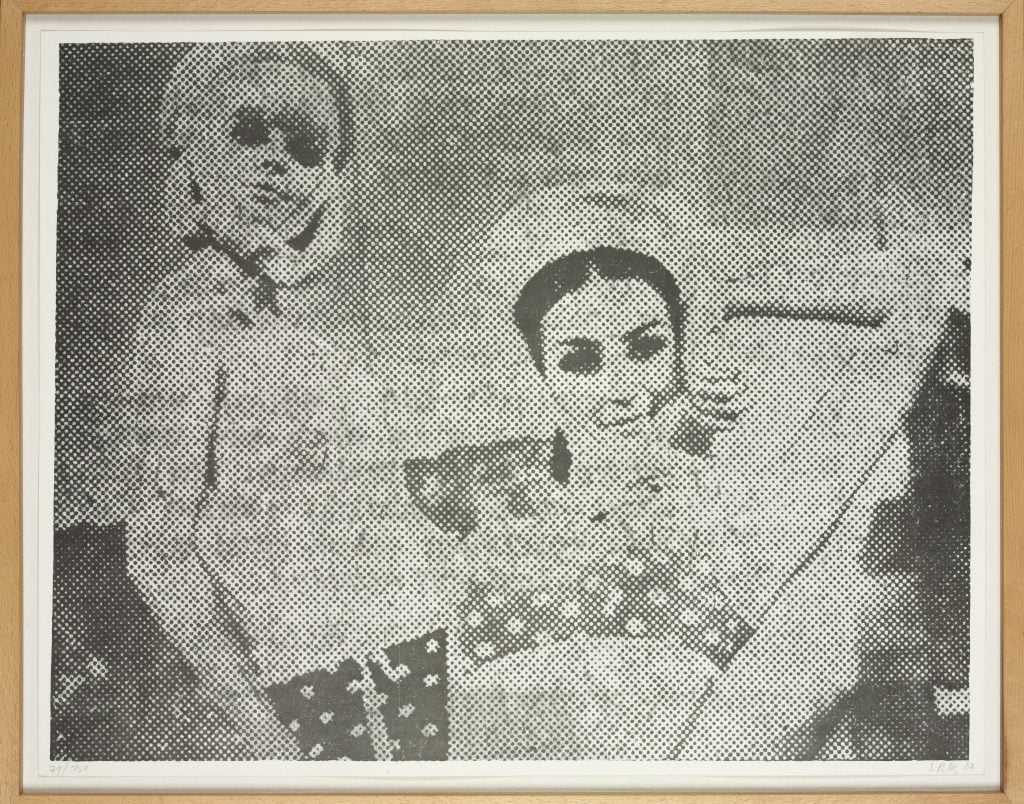

Sigmar Polke, Freundinnen I (1967). Courtesy David Zwirner Books.

In your book, you describe amazing works you saw after World War II, and how they were floating around on the German art market with little to no provenance. Was no one asking any questions?

No, never! It was always fine for me because I bought paintings directly from studios. I focused on artists like Roy Lichtenstein or Robert Rauschenberg—artists that were never in any Jewish collections—and where the provenance was clear. But when buying a Max Ernst, for example, it was never clear. And nobody was asking where it came from. Today, you must give the provenance for as long back as possible.

What do you think about that now, looking back?

It is very difficult. If I buy a Max Ernst, for example, I know the gallery and I know the collector from whom I bought it, so if I have to sell it now, I can tell it is from Gustav Stein, a great collector from Cologne. But where did he get it? He is dead now, so I do not know. If you want to sell it now, you have to prove its provenance, and explain how it was imported. But there are even older things where I have no idea. Through the war, it was not only just Jewish collections that were stolen from, so much was shifted and moved around, so it is very difficult.

Rudolf Zwirner, seated on Franz West’s Liege (Doppelsitz) (1989) under the work Berlin Series (1979) by Gary Kuehn, in his home in Berlin, 2020. Courtesy David Zwirner.

Galleries sometimes pass down through family, but you did not pass your gallery to your son, David—he just went and started one.

That is true. When David was young, he was a musician, but then he decided he was interested in contemporary art. When he decided to become an art dealer, more or less three years later, I closed my gallery. I never wanted to be a father in competition with my son. My advice to him was, if you start this, do it differently. Don’t copy daddy. And he never did. Usually, the kids in galleries are copying the parent, and then it goes downhill.

Everybody should be on top in their own generation. For me, it was clear after 30 years with the gallery that I should stop because you have to be more or less born around the time of your artists. You have to have seen the same movies, read the same literature, so that you understand where they come from. It is very difficult now for me to understand a guy who is 30 years old, virtual connections and today’s literature, but I am not responsible anymore. I collect young art, but just what I like to see, and this is enough.

What kind of artworks are you most interested in?

Drawings. For me, drawings are the most essential way to express yourself. First of all, it is something that is affordable. Secondly, I can keep it easily in my home. I can change them easily. Big paintings need more space. On the drawing, I can see exactly what an artist has in mind. A drawing is like handwriting. I am still interested in art, but not large paintings anymore.

What does success mean to you? You say in your book that your art dealing was not commercially successful.

No it wasn’t, but I was very successful in my life. I was a professor, I made lectures. Then I was curating for years at exhibitions in museums. Now, I have friends in the art world, and a son and a grandson in the art business. It is perfect. What is success? Success is never to be the biggest and the richest. Success is about you being happy in your life, and if you can have a certain influence on your generation.

Give Me the Now is available with David Zwirner Books.