Art World

Israeli Pavilion Remains Shut as Artist Ruth Patir Calls for a Ceasefire and Hostage Release

The curators and the artist representing Israel have decided to keep the doors to the Israel pavilion closed.

The curators and the artist representing Israel have decided to keep the doors to the Israel pavilion closed.

Kate Brown

The artwork is installed, a video work is playing, but the show cannot go on. Artist Ruth Patir, who is representing Israel at the Venice Biennale, and the exhibition’s curators have decided to keep the doors to the Israel pavilion closed as the 60th Venice Biennale opens this week.

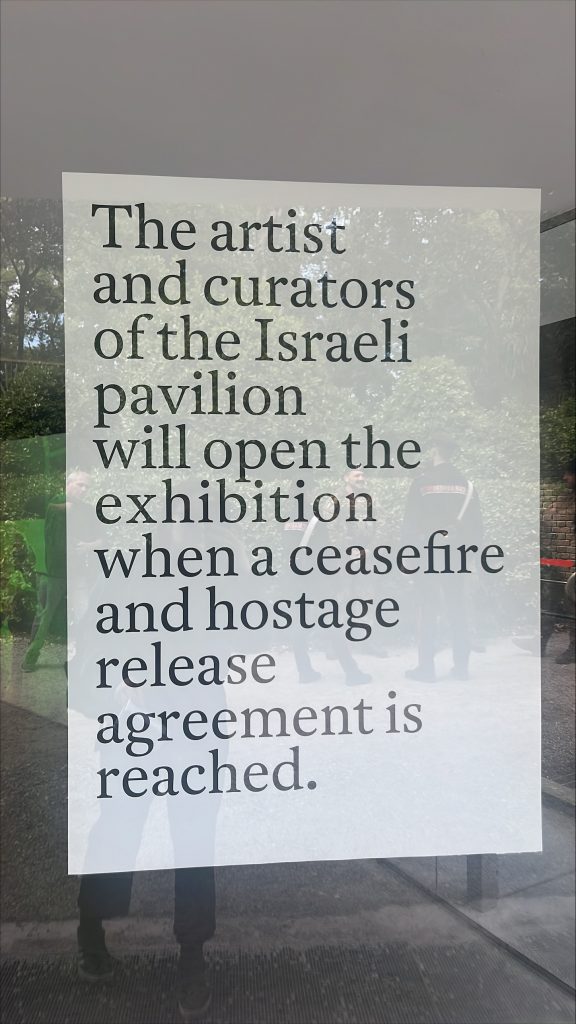

A sign was left on the door to the pavilion, which is located beside the U.S. pavilion in the historic Giardini, stating that “the artist and curators of the Israeli pavilion will open the exhibition when a cease-fire and hostage release agreement is reached.”

Patir, who was announced as the country’s representing artist one month before Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7, made the decision together with the exhibition’s curators, Tamar Margalit and Mira Lapidot, following weeks of calls from pro-Palestine activists to boycott the pavilion.

“We (Tamar, Mira, and I) have become the news, not the art. And if I am given such a remarkable stage, I want to make it count,” said Patir in a statement on Instagram. “I firmly object to cultural boycott, but since I feel there are no right answers, and I can only do what I can with the space I have, I prefer to raise my voice with those I stand with in their scream, ceasefire now, bring the people back from captivity. We can’t take it anymore.”

Visitors will only be able to catch a glimpse of the artist’s work through the windows of the pavilion where her project “(M)otherland” sits under lock and key.

A closure notice from artist Ruth Patir and the exhibition curators hangs in the window of the Israel Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Jo Lawson-Tancred.

Representatives of the Venice Biennale did not immediately respond to a request for comment about the closure.

“In contrast to the political arena, the art world [has in the past] pretended, or aspired, to present something more complex, ambiguous, which could contain internal contradictions – and suddenly in a single blow, the perception changed. You can either be on this side or on the other side,” Lapidot, a curator at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, said to the Israeli newspaper Haaretz in an interview published on Monday in which she said the show would open as planned.

Lapidot added: “There is no longer a way to express empathy and a position that is more than for or against, and that fundamentally contradicts everything I understand about what art is.”

The newspaper also reported that the Israeli Foreign Ministry had confirmed there would be additional security in place at the pavilion.

As art world insiders were pulling up to Venice in vaparettos on Sunday and Monday in Venice, the question circulating was about what kinds of protests may transpire on the grounds of the Giardini this week. For months, pro-Palestinian organizations have been calling on the Venice Biennale to exclude Israel from the prestigious exhibition and for other participating artists to boycott the entire event.

On Tuesday, other national pavilions at the biennale had flyers on view indicating support of Palestine, titled “The Palestine Pavilion: What is the Future of Art—A Manifesto Against the State of the World.” Palestine does not have a pavilion at the event since Italy does not recognize it as a sovereign state.

Security and onlookers stand outside of the shuttered Israel Pavilion at the Venice Biennale on Tuesday, April 16, 2024. Photo: Jo Lawson-Tancred.

In an open letter issued at the end of February, the Art Not Genocide Alliance (ANGA) stated that “any official representation of Israel on the international cultural stage is an endorsement of its policies and of the genocide in Gaza.” Its signatories included the photographer and activist Nan Goldin and artists representing other countries in the Biennale, including artists representing Chile, Finland, and Nigeria. ANGA did not immediately respond to an emailed request for comment.

In response to the open letter, Italy’s culture minister Gennaro Sangiuliano ruled out the possibility of barring Israel from the Biennale. “Israel not only has the right to express its art, but it has the duty to bear witness to its people precisely at a time like this when it has been attacked in cold blood by merciless terrorists,” stated the politician.

Margalit told the New York Times that calling for a cease-fire at such an official capacity, as an artist representing the country, could draw criticism from Israeli lawmakers—the government has covered about half the pavilion’s costs and did not know of the planned protest ahead, Margalit said.

“(M)otherland” explored the patriarchal gaze on motherhood and the pressure on women to become mothers. It draws on her own experience of the medical world and pressure from doctors for her to preserve her chance to become a mother in spite of a medical condition. She recorded her medical appointments for use in her work. A video, slightly viewable from outside in the Giardini, shows broken up fertility goddess sculptures with broken limbs crying out in anguish. Patir told the New York Times that the artwork also reflected her sadness and frustration over the conflict between Israel and Gaza.

Jo Lawson-Tancred provided additional reporting.