Artists

Sabrina Bockler’s Sumptuous Still Lifes Are Enchanting the Art World

The artists's new works are now on view in 'Shallow Water' at Richard Heller Gallery in Santa Monica.

“She is an outlier among the goddesses,” said artist Sabrina Bockler during a recent visit to her Brooklyn studio. “Diana is defined by her autonomy.”

Diana (or Artemis in Greek mythology), the goddess of the moon, childbirth, chastity, and the hunt, is a potent source of inspiration for the rising artist. Her most recent series of paintings are sumptuous and slippery compositions that reimagine ancient myths, hunting scenes, and resplendent, crustacean-laden still lifes that might seem at home in the art of centuries past.

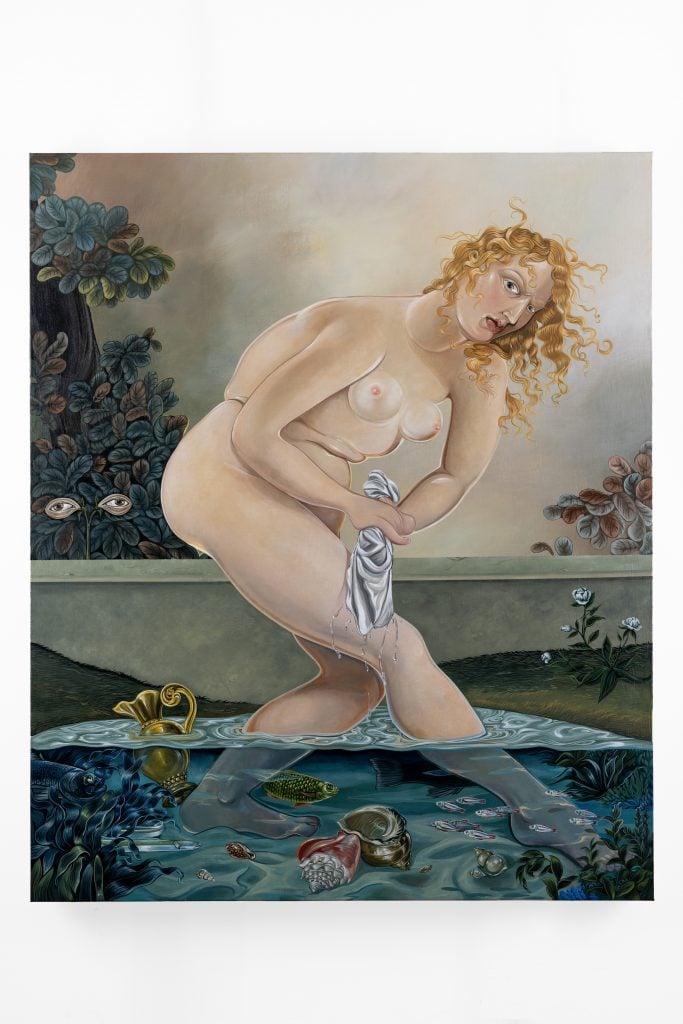

Sabrina Bockler, Private Eyes (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Richard Heller Gallery.

Vividly detailed, these paintings feel anything but stodgy, instead, details of folds of fabrics or overripe fruits possess a near-sentient vivacity. There is reason to stay alert, the paintings, urge. “I pay attention to every corner,” Bockler said “It’s all important.”

On one wall of the studio hung Private Eyes, a large-scale painting of the goddess Diana, naked and bathing in a stream of water. She is bent at the waist, wringing a wet white cloth between her hands, and casts a warning eye out from the canvas, while her golden curls, delicately haloing her face. Bockler considers the painting the keystone to her newest series.

The composition draws upon the myth of Diana and Actaeon, a story in which a young hunter named Actaeon unwittingly stumbles upon the famously chaste goddess Diana nude and bathing with her nymphs. Alarmed by the intrusion, Diana splashes the hunter with water, transforming him into a stag. The hunter’s own dogs, not recognizing their master’s new form, seize upon him, killing him.

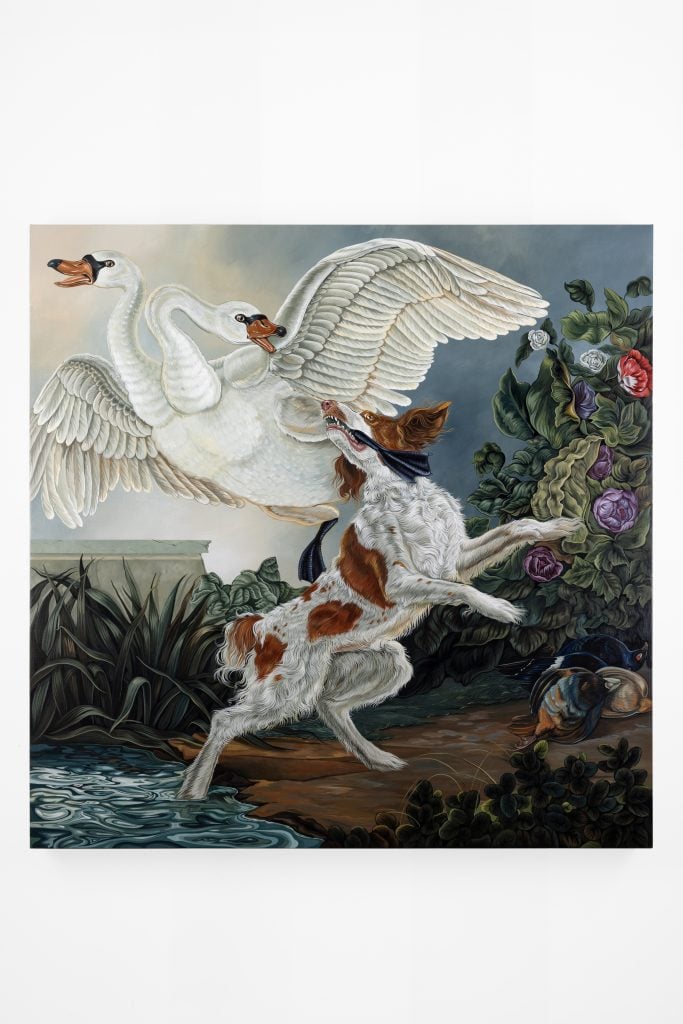

Sabrina Bockler, The Hunt (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Richard Heller Gallery.

“I wanted to capture quiet violence in these new paintings, an invasion while also keeping it in line with a feminine narrative,” Bockler explained of the image.

Beside Private Eyes hung The Hunt, a monumentally scaled scene of a hunting dog ecstatically biting onto the leg of a two-headed swan as it attempts to fly away. The swan, one deduces, is Bockler’s reenvisioning of Actaeon. Twinned and two-headed are many in Bockler’s new works, embodiments of duality and perhaps duplicity. The series is now on view in “Shallow Water” a solo debut with Richard Heller Gallery in Santa Monica (the opening reception has been postponed due to wildfires, but the show remains on view).

This exhibition marks the last of three consecutive solo exhibitions for Bockler, including “Menagerie” at Beers, London, this past May and “Coquette” at Hashimoto Contemporary in New York this past June. Bockler (b. 1987), a graduate of Parsons School of Design, has been a steadily rising figure in the art world over the past five years.

Her distinctive visual language reconsiders and reimagines visual themes and tropes found in art from centuries past, be it 17th-century Dutch still lifes, the sinuous ornaments of the Rococo, or, in her new works, the myths and visions of the Renaissance and Ancient Greco-Roman worlds. But Bockler’s works aren’t nostalgic. Instead, she brings a wry pastiche to her compositions and a tack-like alertness to detail. Her works are rightly situated among contemporary women artists, such as Jesse Mockrin and Ewa Juszkiewicz, who adapt historical motifs to express contemporary truths, particularly regarding women’s bodies.

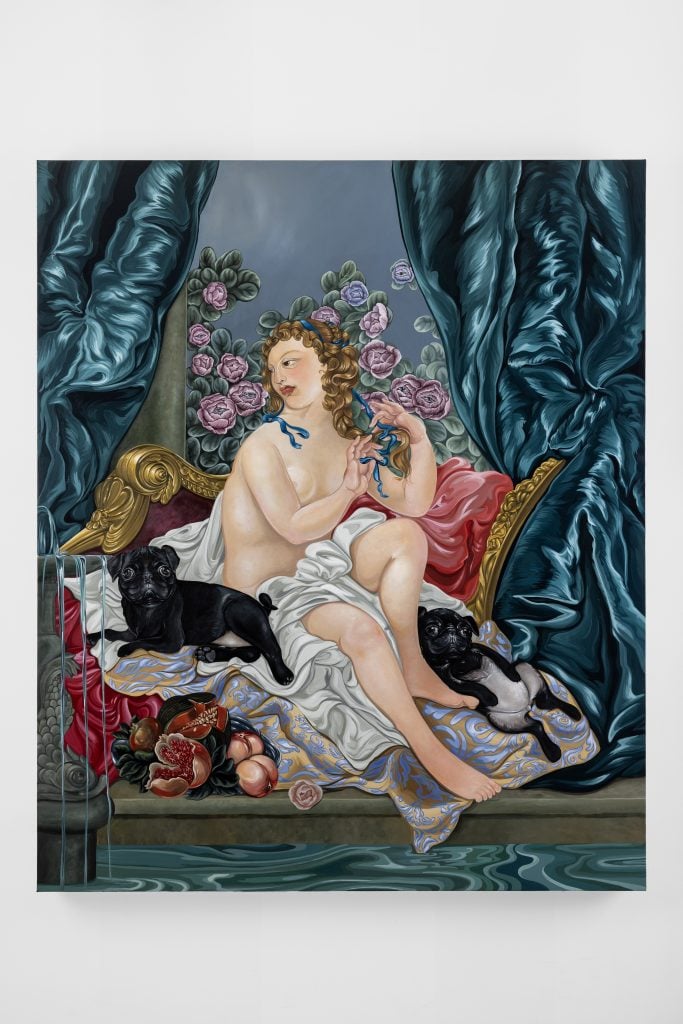

Sabrina Bockler, Through the Glass Darkly (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Richard Heller Gallery.

Now, “Shallow Waters” marks beguiling new territory for the artist; these paintings are Bockler’s first forays into figurative painting (particularly faces) in many years. Centering on still lifes, early works previously alluded to the body through the presence of gesturing hands and arms. In “Coquette,” Bockler’s 2024 painting The Alchemist suggested a deepening interest in depicting the female figure, presenting a neck-down vision of a Madame Pompadour-like mademoiselle.

Here, women protagonists anchor the show. While Private Eyes, Bockler’s vision of Diana, was the first work she completed for her L.A. show (and the hardest to paint, she confessed), when I visited her studio in late November, she was still putting her finishing touches on Symphony, an opulently languid depiction of Venus, goddess of love. Here Venus appears seated on a gilded, red-cushioned settee, pools of luxurious fabrics covering her lap, and fabulous turquoise spilling down behind.

She looks off to the distance, and twirls blue ribbons in her hair, two plump pugs her furry cherubs. While at first, Symphony might seem a pleasant counterpoint to Private Eyes, a woman in repose rather than alarm, the painting soon reveals its own uneasy fluctuations.

Sabrina Bockler, Symphony (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Richard Heller Gallery.

Behind the goddess, a bush of mauve roses grows. Each rose has a single, watching eye at its pistil, suggesting a state of hyper-awareness. What’s more, at Venus’s feet, a split melon shows its seeds like a diabolical toothy grin. Where is this Venus, we wonder? She is perched on a settee on a ledge, a wall behind her in a nowhere space. Below her a body of water rises ponderously high, inching toward her feet, and still yet, water spills from a fountain beside her. Things are not quite as idyllic as they seemed.

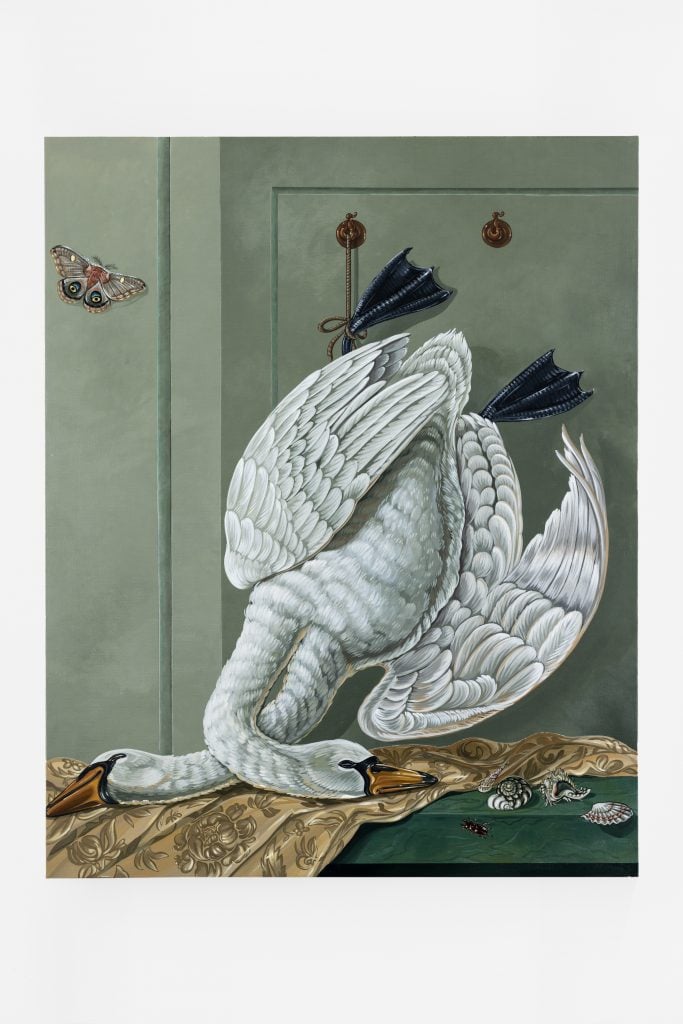

Lurking eyes are here aplenty: on the wings of a moth in Trophy, refracted in the curves of glassware of Through the Glass Darkly, on the leaves of a tree in Private Eyes, a reference to the sprouting eyes of Saint Lucy as painted by Francesco del Cossa. Bockler completed most of these paintings in the lead-up to the presidential election and rooted in contemplations of women’s autonomy.

Sabrina Bockler, Trophy (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Richard Heller Gallery.

Along with these myths, Bockler was also inspired by Ingmar Bergman’s 1960 film The Virgin Spring, a nuanced exploration of the dualities of good and evil, sexual violence, and revenge. For Bockler, the visual language of the past is a window into the various ways women’s bodies have been protected and intruded upon (actual boundaries—walls and ledges—are hinted at here and there).

“Accessing the language of the past can allow me to say something political, but people are willing to receive it in a way,” Bockler explained of her choices. “The messaging in my works is very subtle. But I like for people to feel like they can walk into these paintings and have their own interpretation. There is a lot of symbolism, and culture woven into it, but it’s not for me to say how somebody sees it.”