Regular museum-goers are pretty au fait with the accepted rules: keep your distance from the exhibits, don’t touch anything, and try to be quiet. So what happens when an eccentric museum director expressly encourages you to break them? This is the strange proposition put forward by the Sainsbury Centre near Norfolk, England at its relaunch over the weekend.

As part of the new program, visitors to the museum are invited to interact with the artworks in unprecedented ways, including hugging a Henry Moore or whispering secrets to a Giacometti.

“We are the first museum to ever understand art as a living entity,” the center’s director Jago Cooper told Artnet News. “Great artists are people who have an ability to channel the uniqueness of the human soul into clay or onto a canvas, and materialize an aspect of their anima. At that moment, art captures the life force of the individual.”

The “living art” concept is a passion project of Cooper’s, and the freedom to carry it out was the main condition behind his slightly surprising decision to leave a cushy senior role as Head of the Americas at the British Museum and join this comparatively provincial center in 2021. The idea sounded exciting, but how do these kinds of encounters with “living art” play out in practice? Artnet News decided to give the tour a go.

Step one was a battle with rural phone service providers to download Smartify, a free app offering curated information about museum exhibits somewhat like an audioguide. The first tour, “Living Art,” began with Henry Moore’s Mother and Child (1932). Cooper’s voice in my ear instructed me to embrace the statue, make eye contact with the mother, and then close my eyes and try to summon my earliest memory of being held as a child.

While that memory evaded me, I was encouraged to gently caress the groove running up the sculpture’s back, which was pleasantly smooth and cool to the touch. This sensual moment was compared to Moore rubbing oil into his mother’s back as a child, which he often described as his earliest sculptural experience.

The author hugging Henry Moore, Mother and Child at the Sainsbury Centre in Norfolk, England. Photo: Jo Lawson-Tancred.

“That feeling within you, that feeling of protection, is what Henry was trying to create with this work,” Cooper told me. “Open your eyes and look at this sculpture again, and understand that art isn’t a set of rules to be read, it’s an emotional state of mind to get into.”

I wondered that my actions might damage the sculpture, but Cooper explained that there was video footage of Moore himself telling one of the center’s founders that anyone who thinks they can understand his art without touching it doesn’t know anything about sculpture. Cooper did concede that the work is likely to acquire a patina over time, adding “but that for me is part of the ageing process. I’m not trying to preserve it in a pristine state.”

“Of course, everything has to be done on a very careful, case-by-case basis,” he clarified. “Lots of works of art aren’t designed to touch, but for some things we feel we have clear evidence that it wants to be touched.”

The author moving with three dancing female figures (c. 618-906) at the Sainsbury Centre in Norfolk, England. Photo: Jo Lawson-Tancred.

Next up were three Tang dynasty dancing figures. “These are not static ceramic vessels within a case, they’re living embodiments of movement and dance that has been going on for more than 1,200 years in China,” said Cooper.

As evocative sounds filled my ears, I was encouraged to raise my hands and sway like no one was watching, although I couldn’t help stealing a few sideways glances to ensure that nobody, indeed, was.

“It might feel strange to move like this in the gallery but it might liberate you from the restrictive ways that you’ve been told to engage with art,” promised Cooper. “By letting go of convention, you can open up and connect with art in a much more creative way.”

The author getting close enough to see Francis Bacon’s hair on Study for a Portrait of P.L., no. 2 (1957) at the Sainsbury Centre in Norfolk, England. Photo: Jo Lawson-Tancred.

I sidled over to Francis Bacon’s Study for a Portrait of P.L., no. 2 (1957), depicting his violently abusive partner Peter Lacy. In rousing tones, Cooper established the vibes: “His workshop was a place of alcoholic haze, of cigarettes brushing against the canvas, of trauma and turmoil and angst. You can literally feel the energy within him transfer to the canvas.”

At the audio’s bidding, I leaned in unusually close to the canvas to spot one of Bacon’s hairs on Lacy’s shoulder. Its the kind of detail that reminds us of the immediacy of art-making and that these works are vestiges of real lives lived.

Another interesting aspect of the museum’s relaunch was a second audio tour proposing new ways to inform museum-goers about works in lieu of interpretative wall texts. Listeners can chose to hear from either a maker, an academic expert or someone with lived experience. In the case of a pair of snow goggles, for example, we can hear the perspective of contemporary artist Tarralik Duffy, about the process of carving bone, or from the Greenland hunter Aleqatsiaq Peary, about how the goggles are used.

This tour, said Cooper, “is an attempt to say that the museum isn’t an authority through which the knowledge is given to you to understand art. These are living entities and there’s no right or wrong way to meet them.”

The author viewed by art from within a display cabinet at the Sainsbury Centre in Norfolk, England. Photo: Jo Lawson-Tancred.

A third tour offered yet more experiential encounters with art. “Quite a lot of people who go to galleries and museums don’t like to read lots of text, how do you get them to experience living art?” was the problem to which Cooper kept returning.

Visitors are invited to write themselves a museum label and step into a glass case. Their audience? A crowd of intrigued artworks all staring back.

The gimmick feels fun for a few moments, but what does it hope to achieve? “It is weird, because when you go in there you cannot help but activate your mind that these artworks are living and looking at you,” explained Cooper. “You become objectified and it reverses the agency of the relationship with art.”

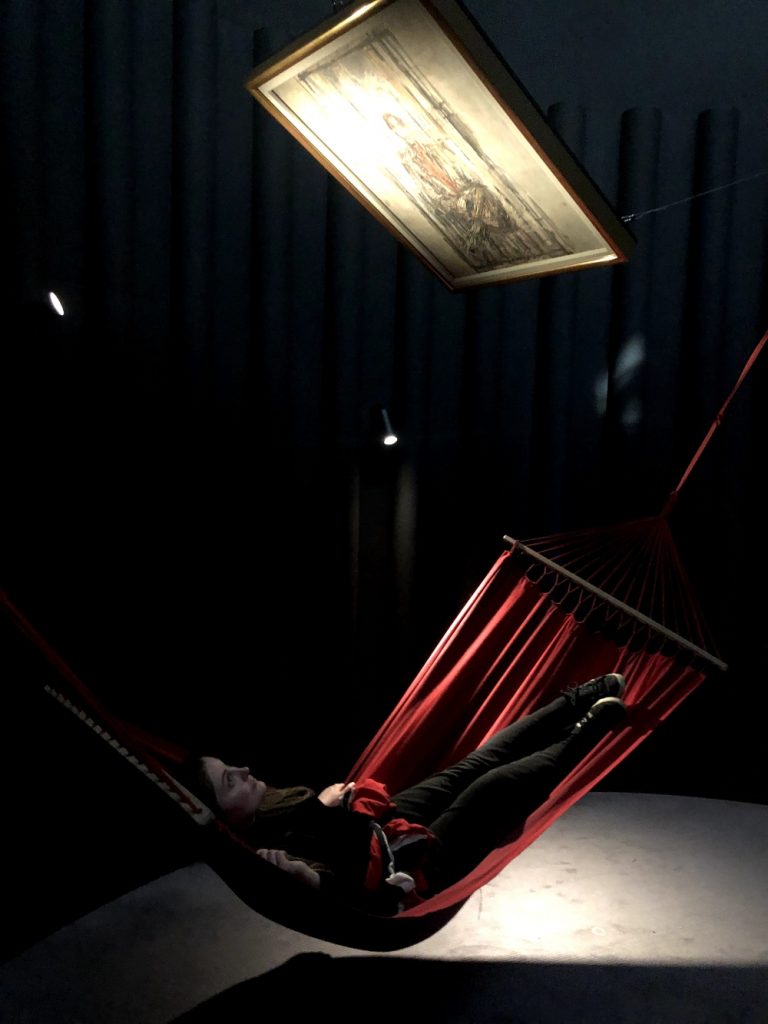

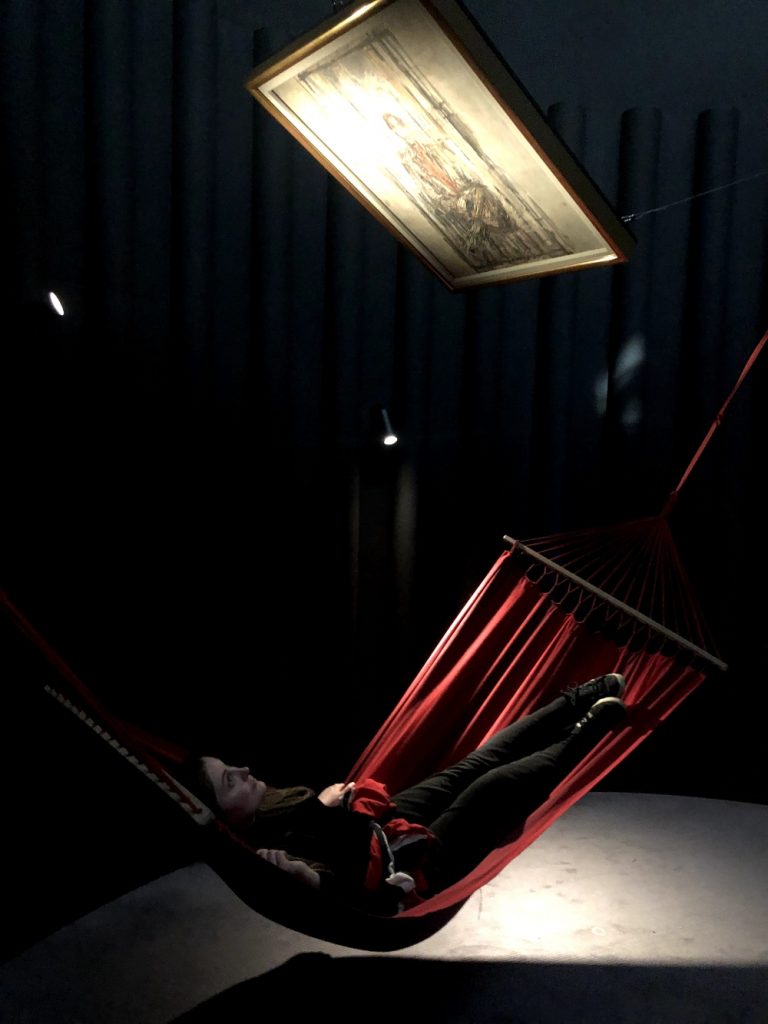

The author lying in a hammock and sharing secrets with a Giacometti portrait at the Sainsbury Centre in Norfolk, England. Photo: Jo Lawson-Tancred.

Duly humbled, I snuck into a circular structure known as the silo, a dark, sequestered nook where a hammock swayed beneath a 1948 portrait by Giacometti of his brother Diego. I couldn’t see a text identifying the painting but, in lieu of a formal introduction, I spotted an ominous sign urging me to “tell it a secret you would never tell a human being.”

“Some people will say art isn’t alive because it doesn’t talk. It’s not true, there is a two way communication,” explained Cooper, who hopes his new methods will help us all deepen the relationships we already form with our favorite pieces of art.

Founded by Robert and Lisa Sainsbury, of U.K. supermarket fame, to steward their trove of over 300 objects, the museum has always sought alternative ways to get visitors engaging with the art. In 2022, the visitor numbers rose to roughly 105,000, an improvement on the pre-pandemic average of 95,000, but it is clear that Cooper is keen to do whatever he can to boost footfall.

To that end, a series of provocative new temporary exhibitions are already in the works that promise to address life’s biggest questions. First up, this fall, is “how do we adapt to a transforming world?” In time, visitors can look forward to asking “what is truth?”, “why do humans still kill each other?” and “what is the meaning of life?” It is clear that Cooper is keen to keep surprising his audiences, how well they will respond remains to be seen.

More Trending Stories:

A Philadelphia Man Paid $6,000 for Cracked Church Windows He Saw on Facebook. Turns Out They’re Tiffany—and Worth a Half-Million

Mona Lisa’s Other Secret—Where the Portrait Was Painted—May Have Been Solved by an Art Historian Using Drone Imagery

A Dutch Museum Has Organized a Rare Family Reunion for the Brueghel Art Dynasty—And the Female Brueghels Are Invited to the Party

The Smithsonian National Museum of African Art’s Director Has Resigned After Less Than Two Years, Citing ‘Resistance and Backlash’

‘We’re Not All Ikea-Loving Minimalists’: Historian and Author Michael Diaz-Griffith on the Resurgence of Young Antique Collectors

The First Auction of Late Billionaire Heidi Horten’s Controversial Jewelry Proves Wildly Successful, Raking in $156 Million

An Airbnb Host Got More Than They Bargained for with a Guest’s Offbeat Art Swap—and the Mystery Has Gone Viral on TikTok

Not Patriarchal Art History, But Art ‘Herstory’: Judy Chicago on Why She Devoted Her New Show to 80 Women Artists Who Inspired Her

An Artist Asked ChatGPT How to Make a Popular Memecoin. The Result Is ‘TurboToad,’ and People Are Betting Millions of Dollars on It

An Elderly Man Spray-Painted a Miriam Cahn Painting at a Paris Museum After Right-Wing Attempts to Censor It Failed

The Netflix Series ‘Transatlantic’ Dramatizes the Effort to Evacuate Artists From France During World War II. Here’s What Actually Happened in Real Life