Art History

How Did a Third-Century Catholic Saint Become a Gay Icon? Here’s the Homoerotic History of Saint Sebastian

Oscar Wilde was inspired by Guido Reni's painting of the saint, along with many others.

Oscar Wilde was inspired by Guido Reni's painting of the saint, along with many others.

Katie White

How did a third-century Catholic saint become a contemporary gay icon referenced on everything from the covers of men’s magazines to art and films and an adopted pseudonym by Oscar Wilde?

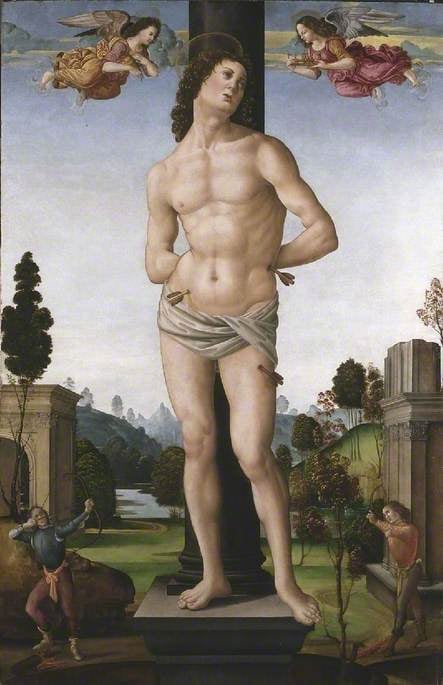

Such is the riddle of Saint Sebastian, a middle-aged Roman soldier killed for converting to Christianity. His story became a favored subject matter in the 16th and 17th centuries painted by artists including Guido Reni, Albrecht Dürer, El Greco, Rubens, Botticelli, and, later, John Singer Sargent. In fact, some have argued that Saint Sebastian may be the most frequently depicted male saint in the Western world—and certainly, there’s no denying a distinct sensuality to these depictions of the saint which often show his youthful body sparingly covered, hips shifting with contrapposto, narrowly waisted, and his gaze cast toward heaven, with an expression caught between torment and transcendence.

But who was Saint Sebastian really and how, when, and why did this curious exultation to the status of gay icon occur? To mark the final days of Pride, we’re sharing what we’ve discovered below.

Tommaso, Martyrdom of St Sebastian (1490–95). Collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum.

Despite Saint Sebastian’s popularity in art history, the details of his life are sparingly few. Saint Sebastian is venerated as an early Christian martyr and a saint by the Catholic and Orthodox churches and, according to fifth-century hagiography, during the Diocletian Persecution of Christians (one of the last and most brutal attempts by the Roman Empire to quash the spread of Christianity) Sebastian, a member of the Praetorian Guard, was sentenced to death by the reining pagan Emperor Diocletian for espousing the teachings of Christianity.

Nicolas Régnier, Saint Sebastian Tended by Saint Irene (c. 1625).

He was tied to a tree and soldiers shot him with arrows, but according to Christian lore, Saint Sebastian miraculously survived, having been rescued and healed by Saint Irene of Rome. This scene of affliction and survival would become a popular artistic theme as early as medieval times, only growing more common in 16th- and 17th-century European painting.

Sebastian’s actual martyrdom, however, came after this initial assault. Having recovered, the saint attempted to confront the Diocletian face-to-face about his persecution of Christians. Guards clubbed the saint to death and his body was dumped into a sewer, only to be later recovered by Saint Lucy and buried in a Roman catacomb, where his remains are still today enshrined at the Basilica of St. Sebastian Outside the Walls.

Josse Lieferinxe, St. Sebastian Interceding for the Plague-Stricken (1497).

Throughout the centuries, Saint Sebastian’s myth and legacy have shifted with cultural interests. During medieval times, Saint Sebastian was embraced as a patron of divine protection and culturally aligned with the god Apollo, resulting in the saint’s depiction as a beautiful and youthful young man (though often clad in armor, in keeping with his life as a soldier). With the emergence of the Black Death, however, his likeness shifted to one of a grizzled older man, more aligned with his historical age. His popularity as a protective intercessor against disease grew, however, and with it, his return to youthful attractiveness.

By the dawn of the Renaissance, artists were emulating prototypes of masculinity associated with the Greek world, and Saint Sebastian transformed into a figure of ephebic beauty—adolescent, lithe, idealized in form, and often covered only by a loin cloth. These images showed the saint, not in his actual moment of martyrdom, but in a more poetic moment of torture by arrows. Indeed, these Renaissance and Baroque depictions are rooted in the Catholic teachings about the permeability of saints’ bodies and the ecstasy experienced in their communion with the divine—these depictions were the ones to be later embraced by the gay community who saw their own experiences mirrored in Saint Sebastian’s beautiful suffering.

El Greco, St. Sebastian (1612). Collection of el Museo del Prado, Madrid.

In the modern era, the popularization of Saint Sebastian as an icon in the gay community often leads back to Guido Reni’s Martyrdom of St. Sebastian (c. 1615) arguably the most famous depiction of the saint (Reni painted six versions). Oscar Wilde was known to have adored the work, which is in the collection of the Palazzo Rosso, in Genoa. In fact, Wilde went so far as to adopt the pen name Sebastian while exiled in Paris during the last years of his life.

Reni’s painting was similarly influential to the famed 20th-century Japanese author Yukio Mishima; in Mishima’s 1949 novel Confessions of a Mask, the book’s adolescent protagonist experiences a homosexual awakening while gazing at the very same painting. The references to the saint didn’t end there—Mishima, who was himself gay, went so far as to pose as Saint Sebastian in a now-infamous photographic portrait, taken not long before the writer’s death by suicide in 1970. The photograph further cemented associations between the ecstasy and torments of the saint’s martyrdom with the homosexual experience of persecution throughout the 20th century. Wilde, himself, it should be noted, had been exiled in Paris, following a nearly two-year imprisonment at Reading Gaol in England for the crime of practicing homosexuality.

In the visual arts, too, these allusions to the saint have cropped up repeatedly throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. In the 1970s, Italian artist Luigi Ontani staged a provocative photograph of Saint Sebastian as a gay icon. In the 1976 film Sebastiane, filmmaker Derek Jarman engaged with the narrative of the saint to explore ties between sexual and spiritual ecstasy, through a specifically homoerotic lens.

But what about these depictions of Saint Sebastian so resonated with the likes of Wilde and Mishima? Many observers, including Susan Sontag, have noted that Sebastian doesn’t yell out in anguish amid his wounding but endures the torment with an expression caught between pain and pleasure. Sontag called him the “exemplary sufferer.” His head is often flung back or forward rapturously. He conceals the depth of his emotions, experiencing both torments and pleasures privately, a feeling similar to the experience of gay identity for many men in the 20th century (and often to this day).

Others have interpreted the arrows piercing the saint’s body as phallic allusions and disguised references to homosexual sex, while his rope-tied hands can be seen through the lens of sadomasochism. Perhaps most concretely, the story of Saint Sebastian paralleled the experiences and fears of the closeted gay community—when Sebastian’s concealed true (Christian) identity was revealed, he was shunned, tormented, and killed by those in power, a harrowing tale that mirrored the gay experiences of being “outed” throughout modern history.

Interestingly, references to the saint by gay artists have continued to shift in more recent history. During the AIDs crisis, artists including Keith Haring and David Wojnarowicz. who would both die from the disease, found solace not in the saint’s ecstasy but in his earlier medieval associations with healing and warding off the plague, both incorporating references to this patron saint of the gay community into their late artworks.