Art World

Wait, Why Are So Many Dogs Smoking Joints in Old Art? We Looked Into It, and the Answer Is Pretty Far Out

A very important art-historical investigation.

A very important art-historical investigation.

Ben Davis

True museum heads know the feeling.

You’re walking through your favorite art institution, among the European Old Master or Spanish Colonial paintings, when suddenly, you think… wait, is that dog smoking a huge joint?

I first noticed it years ago in the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana, where I came upon this delightful painting of a dreaming woman.

Anonymous, Beata Juana de Aza (18th century). National Gallery, Cuba.

And there, in the top corner, I found this. Seems pretty clear what’s going on!

Detail of Anonymous, Beata Juana de Aza (18th century).

Once you know the motif, you will find it cropping up again and again. So, you’d discover the Smoking Dog in paintings like this one.

Anonymous, St. Dominic. Museo de Bellas Artes de Córdoba.

Here’s our canine friend up close, looking like the life of the party.

Detail of Anonymous, St. Dominic. Museo de Bellas Artes de Córdoba.

Other times, the dog will appear to be passing around a large joint, like so.

Luis Tristán, St Dominic in Penitence (1618). Museo del Greco, Toledo.

Would it surprise you to know that these paintings are not, in fact, supposed to represent a dog smoking a joint?

The dog with a flaming stick in his mouth is a motif known as the “Hound of St. Dominic.”

The woman often depicted with the dog is Saint Jane (or Santa Juana) of Aza, and it is a reference to a vision she had (hence the daydreaming posture). Blessed Jane is said to have dreamed that she was carrying a small black-and-white dog with a blazing torch in its mouth in her womb. When she gave birth to it, the dog ran out and set everything on fire. This vision was interpreted to mean that Jane’s son was going to have an influence that would spread over the whole world.

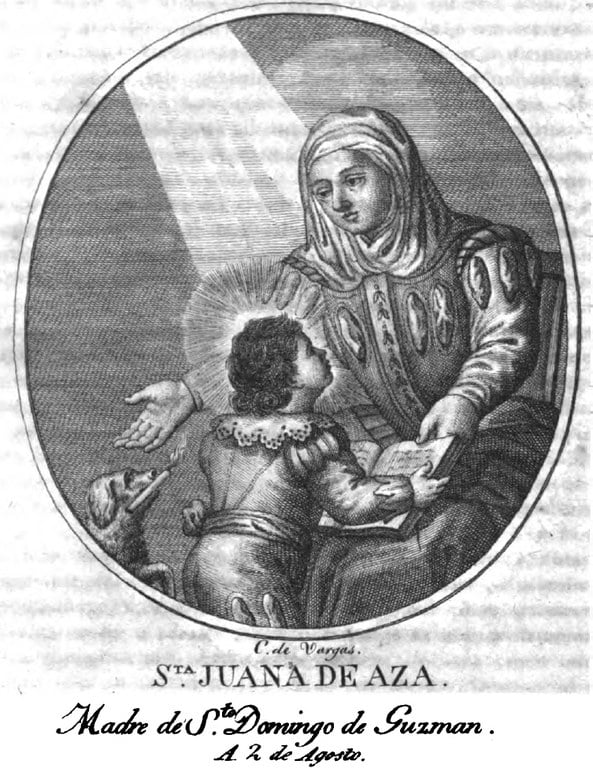

Cayetano Vargas Machuca, Santa Juana de Aza, Madre de Santo Domingo de Guzmán (1829).

Her son would become Saint Dominic, or Santo Domingo. Here he is, resplendent, a very cheerful version of the Smoking Dog at his side.

Claudio Coello, Saint Dominic of Guzmán (1685). Museo del Prado.

Dominic, of course, founded the Dominican Order of Preachers in 1216—thereby setting the world on fire, metaphorically, in terms of spreading the faith. As a matter of fact, Dominican preachers were sometimes called “Domini canes,” or dogs of the lord.

The reference back to his mom’s dream is often suggested in art by the association of his dog with a globe. In many cases, the dog will be pressing the flaming torch to it to convey the idea of setting the world ablaze (and thereby also suggesting a great idea for a novelty ashtray).

José Gil de Castro, Santo Domenico (1817). Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Santiago.

Consider this “family tree” of the Dominican order.

Anonymous, Genealogical tree of Dominican Order (1804). Rights: Museo de Artes Universidad de los Andes.

There is Santo Domingo, at the root of it all, bottom right—and the black-and-white Smoking Dog beside him.

Detail of Anonymous, Genealogical tree of Dominican Order (1804).

Because the Virgin Mary is said to have gifted Saint Dominic the rosary in a dream, you will often find our mellow dog friend present in paintings of the episode.

Anonymous, Madonna of the Rosary and Saint Dominic (1850/1899). Santuario e Sacro Monte de Oropa.

There he is!

Detail of Anonymous, Madonna of the Rosary and Saint Dominic (1850/1899).

Sometimes, the smoking dog is a more unexpected presence, as in this illumination.

Master of James IV of Scotland, Saint Dominic (ca. 1510–1520). J. Paul Getty Museum.

Here we find pooch sneaking a smoke beneath the desk.

Detail of Master of James IV of Scotland, Saint Dominic (ca. 1510–1520).

Here’s one of my favorites: a particularly pensive Santo Domingo.

Antonio del Castillo, Santo Domingo de Guzmán (ca. 1650). Museo de Bellas Artes de Córdoba.

Check out his dog companion—with those great bloodshot eyes.

Detail of Antonio del Castillo, Santo Domingo de Guzmán (ca. 1650).

In any case: long story short, the Smoking Dog is not a smoking dog. Get that out of your head. It’s in fact a storied bit of iconography, and fascinating to learn about. But it’s hard to unsee once you’ve seen it.