What to do with problematic historical artists.

It is a quandary that regularly dogs art historians, curators, critics, and the public at large regarding numerous high-profile artists of times past. In the list of controversial historic artists that give viewers pause, Jean-Léon Gérôme certainly ranks rather high. Credited with popularizing Orientalist painting to a fever pitch in the 19th century, the influence of Gérôme and his particular brand of Orientalism has seeped into Western depictions of the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia (MENASA) region today, more than a century later.

Unpacking Gérôme’s work and legacy is the subject of a three-part exhibition “Seeing is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme,” jointly produced by the in-development, future Lusail Museum and Mataf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, both of Doha. While the first section curated by Emily Weeks, “A Wider Lens, A New Gérôme,” presents a comprehensive look at Gérôme’s practice and oeuvre, the latter two sections trace the evolution of Orientalism within visual culture through the present and offer insight into how contemporary artists engage with the theme.

In the comparatively concise second section of the exhibition dedicated to photography and titled “Truth is Stranger than Fiction,” which operates as a sort of steppingstone taking visitors from the 19th century and into the 20th, curator Giles Hudson showcases how Gérôme’s techniques, most powerfully his use of color, have influenced subsequent generations of Western artists. Featuring a selection of 19th-century photographs illustrating the milieu of Gérôme’s time, more contemporary examples illustrate the enduring, and in some regards nefarious, ways his legacy lives on.

Installation view of work by Steve McCurry in “Seeing is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme” (2024). Courtesy of MATHAF: Arab Museum of Modern Art and Lusail Museum, Qatar Museums, Doha.

In a suite of photographs by American photojournalist Steve McCurry, including the iconic Afghan Girl that appeared on the June 1985 cover of National Geographic, the images are vibrant and hyper-saturated, echoing the color schemes of Gérôme that signaled the subject matter as being “exotic.” Inclusions of more contemporary photographs by artists from the MENASA region show emerging artists co-opting these means as well as incorporating symbols and motifs (but with actual knowledge of them) to craft new visions for the future. Underscoring the reciprocal influence between Gérôme and photography, where Gérôme tapped the compositional structures of the lens-based medium in his painting to convey a sense of reality, photography in turn found painterly opportunities to sidestep reality and incorporate elements of fantasy.

Outside of the context of the present show, Western audiences, specifically Americans, might recognize this type of color signaling from the way television shows and movies frequently use colored filters to convey a sense of place; for instance, paralleling the motivations of Orientalism, countries part of the Global South are often shot with a yellow filter.

The first two sections were brought together by curators tapped by the Lusail Museum, an institution which will boast the world’s largest collection of Orientalist paintings. The third section “I Swear I Saw That” curated by Sara Raza, however, speaks to Mathaf’s specialization in Modern and contemporary art. It stands as a cogent exhibition on its own terms.

Moving away from the direct impact of Gérôme espoused in “Truth is Stranger Than Fiction,” here Raza approaches the idea of Orientalism not from a Western perspective but from a multiplicity of Eastern ones.

Babi Badalov, Text Still (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha.

Questioning the East/West Dichotomy

Describing her approach to curating “I Swear I Saw That” in a guided walkthrough of the show, Raza said, “It was a way to think through how artists’ hands become a poetic weapon, and to rethink Orientalism, but not in a didactic way. There’s a time to be like a blunt hammer, and there’s a time to be a little bit more poetic.”

The exhibition section features 25 artists, with the work of each showcased on its own merits rather than lumped together into thematic groupings (i.e., like a “blunt hammer”), together forming a new contemporary vision of the MENASA region through artistic means and considering the ways it has historically been illustrated. “Collectively, they come together to re-think Orientalisms in the plural,” said Raza. “Orientalism in this section becomes a conversation between East and East. Interrogating where the endpoints of Europe meet, if you flip that, that’s the East. We start to think about the arbitrary nature of borders, space, human geography, and so on.”

The start of this interrogation begins before visitors enter the exhibition, and even the museum building itself. One of two specially commissioned works for the show, installation work Text Still (2024) by Azerbaijani artist Babi Badalov envelops the exterior of Mathaf, comprised of collaged and stitched together fabric panels emblazoned with texts employing a range of alphabets such as Arabic, Cyrillic, and Latin. Playing with the elements of language itself, like grammar and syntax, as well as experimenting with various forms of stylized rendering of text like those found in graffiti or street art, Badalov’s work questions assumed hierarchies of language and culture as perpetuated by Orientalist lines of thinking. Even when figuration or illustration is absent, text is a common indicator of place, but within Text Still, the boundaries between alphabets and languages are metaphorically broken down and presented on a level plane.

Ergin Çavuşoğlu, Quintet without Borders (2007). Courtesy of the artist and MATHAF: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha.

Within the exhibition space itself, a video work by Ergin Çavuşoğlu, originally from Bulgaria and now based in London, more directly addresses, or rather abstracts, ideas around borders whether East and East or East and West. Quintet without Borders (2007) shows five Roma musicians playing music in five different places. The video recordings are synced so the result is a cohesive performance of a piece of music that contains elements from a range of musical traditions, reflecting the composers’ nomadic origins. The Roma people originated from the region of Rajasthan on the Indian subcontinent, but a series of westward migrations largely between the 5th and 11th centuries codified a tradition of nomadism, which extends through the present day. The itinerant lifestyle lends itself to a decidedly different conception of borders and movement through various lands, one at stark odds with contemporary notions of geography. Quintet without Borders interprets through poetic, and musical means an old to Roma but perhaps new to Westerners’ perspective on time, place, and culture.

East and East

While discourse around the East/West dichotomy has become well-trodden ground, confining Orientalism to a dynamic between Europe and the Near East paints only a fraction of the picture. Even the concept of “MENASA” itself is a construction.

“That the idea of geography and space in the Muslim world isn’t just limited to terms like MENASA, WANA [West Africa North Asia], MENA. Nobody from this region ever refers to themselves as that and I’m from here,” Raza noted. “That’s really important to point out, that these are also terms that have a military connotation. They are fictional and the way in which East is constructed is also fictional. The Middle East and West Asia and North Africa, it was entirely created as a mythical space. Edward Said writes, of course, about this in Orientalism, and on the cover of Orientalism is the work of Gérôme, The Snake Charmer, except Said never, ever mentioned Gérôme by name. But an image is worth a thousand words.”

These “military connotations” are not only the result of European interventions, but, for example, the Russian and later Soviet conquest of Central Asia, and the expansion and contraction of the Ottoman Empire. In both cases, forms of Orientalism outside Western constructs developed.

Installation view of Farhad Ahrania, “Khatamkari” (2018–19). Courtesy of the artist and MATHAF: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha.

Examples of contemporary dialogues with this history of non-Western Orientalism include works from Iranian-British artist Farhad Ahrarnia’s ongoing series that employs khatamkari, an ancient Persian art of marquetry, or inlaying technique. Here, Ahrarnia leverages this traditional practice in conversation with Soviet Modern art, specifically the work of Russian artist Kazimir Malevich. Western modes of Modernism are in turn relegated to the periphery, underscoring the falsity of Western universalism—artistic or otherwise.

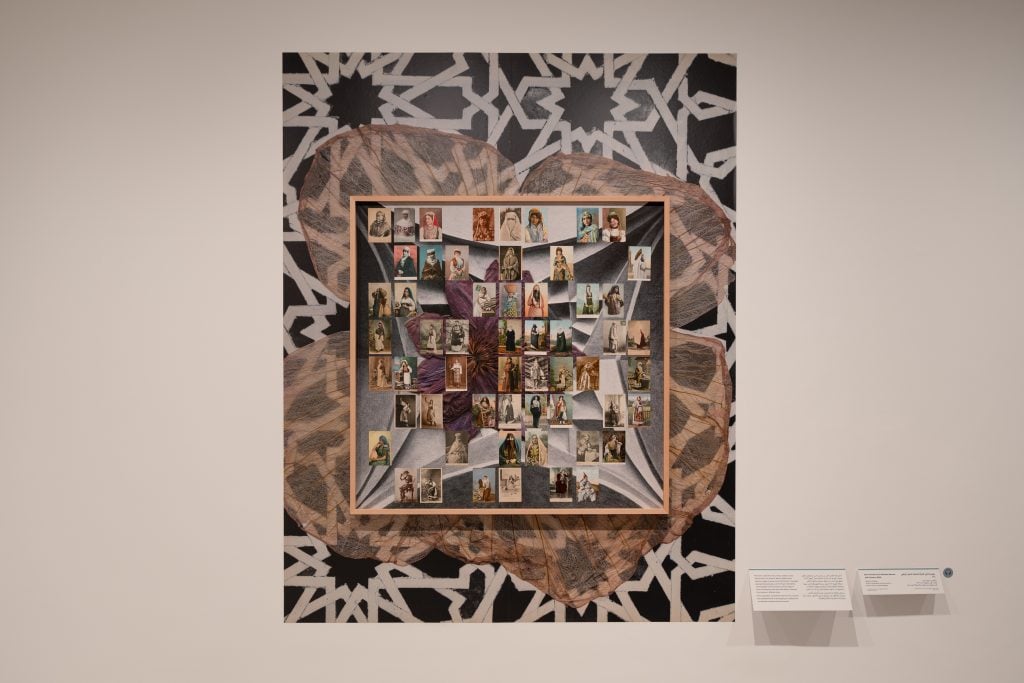

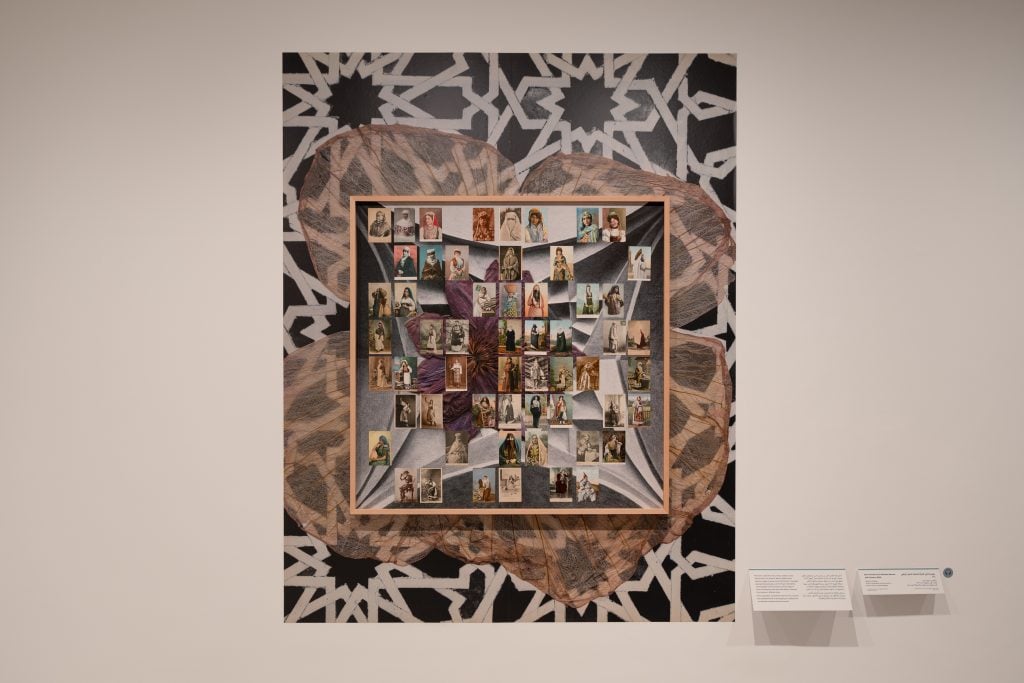

Aikaterini Gegisian, Self-Portrait as an Ottoman Woman with Flowers (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Courtesy of MATHAF: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha.

Turning the equation in on itself are works such as Self-Portrait as an Ottoman Woman with Flowers (2024) by Aikaterini Gegisian. Building on a project undertaken by the artist between 2012 and 2016, the work features a range of postcard reproductions of women in various forms of pose and traditional dress from across the Ottoman Empire, reflecting a type of Orientalist ethnography. Coupled with dried flowers and images of Islamic architecture, Gegisian’s own organization of the work’s various parts becomes a feminist action, complicating hierarchies of identification.

Contemporary Orientalism

While Gérôme’s legacy is more of an abstract starting point for the “I Swear I Saw That,” it nevertheless provides a strong conceptual basis for recent artistic engagement with contemporary forms of Orientalism. The explorations are not just the body of work of one man, but an index of forms, colors, and symbols used as didactic indicators—regardless of their roots in either reality or fantasy.

“It’s very easy to sort of just say, ‘OK, Gérôme is designated to the dustbin of art history,’” Raza observed. “But then how do we look at his work again within the revisionist lens? How do artists allow us another way to explore the work? And I think that’s really key in thinking about not only the art historical content but visual culture as a larger whole.”

Installation view of work by Raeda Saadeh in “I Swear I Saw That” (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Courtesy of MATHAF: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha.

Tapping into this vernacular, Palestinian artist Raeda Saadeh presents works from her “Fairy Tale” series, including Who will make me real? (2003). In this work, the artist photographs herself in the position of the Odalisque, typically shown in Western traditions as reclining, enveloped in news clippings.

“You start to see two elements at play: one is misinformation, and one is disinformation. To some degree we can sometimes forgive misinformation because it might just be factual inaccuracy,” said Raza. “But disinformation is very intentional, designed to displace and mobilize the masses in a very particular way. We start to see how Orientalism takes shape in other intellectual deposits as well as the news. The news has a viral capacity to generate very particular kind of meaning.”

By wrapping her body in these numerous and overlapping news clippings and through the work’s title, Saadeh engages with the media’s frequently Orientalist representation of Palestinian peoples, as well as her own physical and psychological experience of living under occupation. Unlike the traditional, docile Odalisque pose, however, Saadeh gazes directly out at the viewer in confrontation.

Installation view of Nadia Kaabi-Linke, One Olive Tree Garden (2024). Courtesy of the artist and MATHAF: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha.

In the second commissioned work for the show, One Olive Tree Garden (2024), Tunisian and Ukranian artist Nadia Kaabi-Linke presents an olive tree that has been cast in concrete and meticulously sliced, the pieces of which can be moved through and circumvented by visitors. Described by Raza as a type of “biopsy of a tree,” the work holds a multitude of references that, together, form a new perspective on Orientalism. Within the exhibition, the work alludes to Gérome’s painting La République (1848–49) which depicts the personified Republic with an olive branch. In Kaabi-Linke’s work, the tree rings (which are tapped within concrete and dissected) appear almost like a form of inscrutable cartography, evoking maps and borders, but cartography’s penchant for interpretation, paralleling the myth that is Orientalism.

Jean-Léon Gérôme, La République (1848–49). Collection of the Musée des beaux arts de la ville de Paris.

“Orientalism functions as a very unprogressive form of nostalgia,” said Raza. “There are nostalgic elements—there are colors, postures, scenes that evoke certain feelings. Perhaps they are beautiful in their detail. What largely projects onto external reality is what we’re trying to look at and ask: how do you exist as contemporary without cutting off the past?”