Reviews

At the Mayor’s Mansion in New York, a Powerful Art Show Honors the Diversity of 100 Years of Women’s Struggles

'She Persists' is part of First Lady Chirlane McCray's efforts to activate the mayor's home as the 'People's House.'

'She Persists' is part of First Lady Chirlane McCray's efforts to activate the mayor's home as the 'People's House.'

Eleanor Heartney

Gracie Mansion is a stately home with a complicated history. The Federal style residence was built on the East River in 1799 as a country house for a slave-holding Scottish merchant named Archibald Gracie. After passing through various owners, it fell victim to tax foreclosure in the late 19th century. Taken over by the city, it was downgraded to a park concession stand and public restroom. Then, in 1943 Robert Moses pushed to designate it the official residence of the mayor of New York. City officials agreed, arguing that it offered the mayor greater safety during wartime. Enlarged with a new addition during the Lindsay administration in 1966, Gracie Mansion underwent a major restoration in the 1980s when Mayor Ed Koch opened sections of the private living quarters to public view.

The mansion’s recent history has been bumpy. In 2001 it was embroiled in Rudy Giuliani’s messy divorce. On taking office in 2002, Michael Bloomberg privately financed much needed renovations but refused to live there. Instead he declared that henceforth the house should just be a museum. With the de Blasio administration, Gracie Mansion has returned it to its historic use. The de Blasio family lives there, and First Lady Chirlane McCray has been developing programs to underscore its newly designated status as the People’s House. And so, in the last five years, the mansion’s walls have hosted a series of exhibitions that stress both the triumphs and the less salutary aspects of New York history.

This newly minted tradition continues with “She Persists: A Century of Women Artists in New York,” an installation of works by over 40 women artists scattered throughout the public and semi-private areas of mayor’s home. Curated by Jessica Bell Brown, “She Persists” appears on the centenary of the passage of the 19th Amendment ensuring women the right to vote. In keeping with this history, the exhibition’s title invokes the increasing assertiveness of women in public life with an echo of Mitch McConnell’s attempt to shut down Elizabeth Warren on the Senate floor (“She was warned… Nevertheless, she persisted.”) But the title could as well stand for women’s tenacious struggle to be recognized for their extensive contributions to the cultural life of the city and the country.

The opening reception for ‘She Persists: A Century of Women Artists in New York 1919-2019’ at Gracie Mansion on Tuesday, January 22, 2019. Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office

The works span the 1920s to the present and represent both celebrated and lesser-known figures. They are hung without reference to chronology and play off of one another and the domestic interiors that sometimes threaten to overwhelm them.

One starting point is Florine Stettheimer’s The Cathedrals (sadly appearing only in reproduction as the Metropolitan Museum of Art was unwilling to lend the originals), shown in the foyer that serves as entrance to the Mansion. These infectious works were painted between 1929 and 1942 in Stettheimer’s confectionery colors. They celebrate four of the wonders of New York City, namely Broadway, Fifth Avenue, Wall Street, and Art. Together, they offer a joyful vision of New York as a fantasy world of elegant urban sophisticates bathed in glittering lights and surrounded by opulent architecture.

Florine Stettheimer, The Cathedral of Art (1942). Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

But there is an alternate opening to the show, provided by a work that might be The Cathedrals‘ dark twin. Lurking outside on the grounds near the side entrance to the Mansion is Kara Walker’s Invasive Species (to be placed in your Native Garden) (2017). This ominous bronze sculpture comprises a tar-like blob that suggests an amorphous figure with severed feet. The title points to the status of “outsiders”—the slaves, native Americans, immigrants, and undocumented workers—who have “invaded” and then been absorbed into the fabric of New York City life. It suggests a stark contrast to Stettheimer’s glamorous New York, and a very different vision of the city whose symbol is the Statue of Liberty.

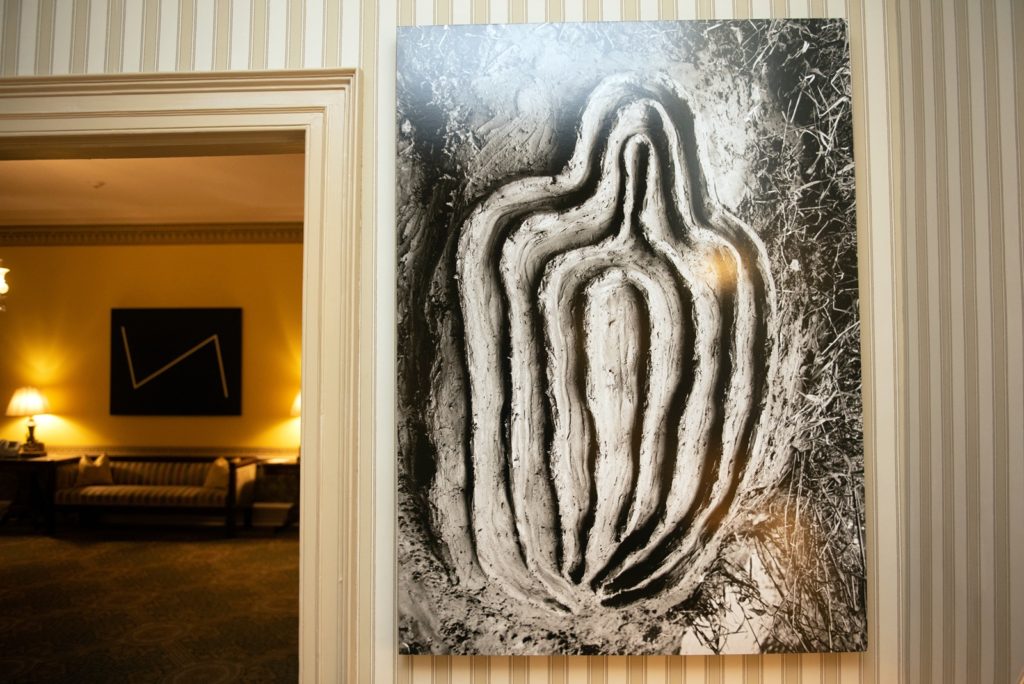

Ana Mendieta, La vivacación de la Carne (Vivification fo the Flesh) (1982). Image courtesy Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office.

And so it goes with this exhibition, as different versions of New York are suggested through the works of women artists. Some works blend almost seamlessly into the Federalist décor and period furniture (and in the case of several lounge chairs and a table by Florence Knoll, actually are the furniture). Others, for instance a Guerrilla Girls poster in the ballroom or a photograph of Ana Mendieta’s vaginal La La Vivacación de la Carne in the Gracie Foyer, are intentionally abrasive. But even the more apparently congenial works often have a bite.

Elizabeth Colomba, Haven (2015). Image courtesy Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office.

Elizabeth Colomba’s Haven (2002) is hung above a mantle in the Peach Room (the mansion’s rooms tend to be designated by their often vibrant colors). It is a portrait of a well-dressed Civil War-era couple surveying their property in a manner that brings to mind the self-satisfied country squire and his wife in Gainsborough’s Mr. and Mrs. Andrews (1750). Except here the couple is African American and the figures turn away from us toward their house with a look of unease. A carving on the tree behind them indicates that this is Weeksville, a community founded by free blacks in Brooklyn in the early 19th century.

Similarly, at opposite ends of the ballroom, two floral paintings face off against each other. What is at first glance a pair of decorative still lifes in fact has a darker undercurrent. Theresa Bernstein’s Flower Piece (1943) is realized in the subdued colors of the Ashcan School with which she was associated. The work is signed “T. Bernstein,” the identification the artist chose to mask her gender following rampant discrimination against her as a woman artist.

Jennifer Packer, Say Her Name (2017). Image courtesy Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office.

Opposite it, Jennifer Packer’s 2017 gestural painting is a funerary bouquet commemorating Sandra Bland, the African American woman who was found dead in her jail cell following her arrest for a traffic violation. It is poignantly titled Say Her Name.

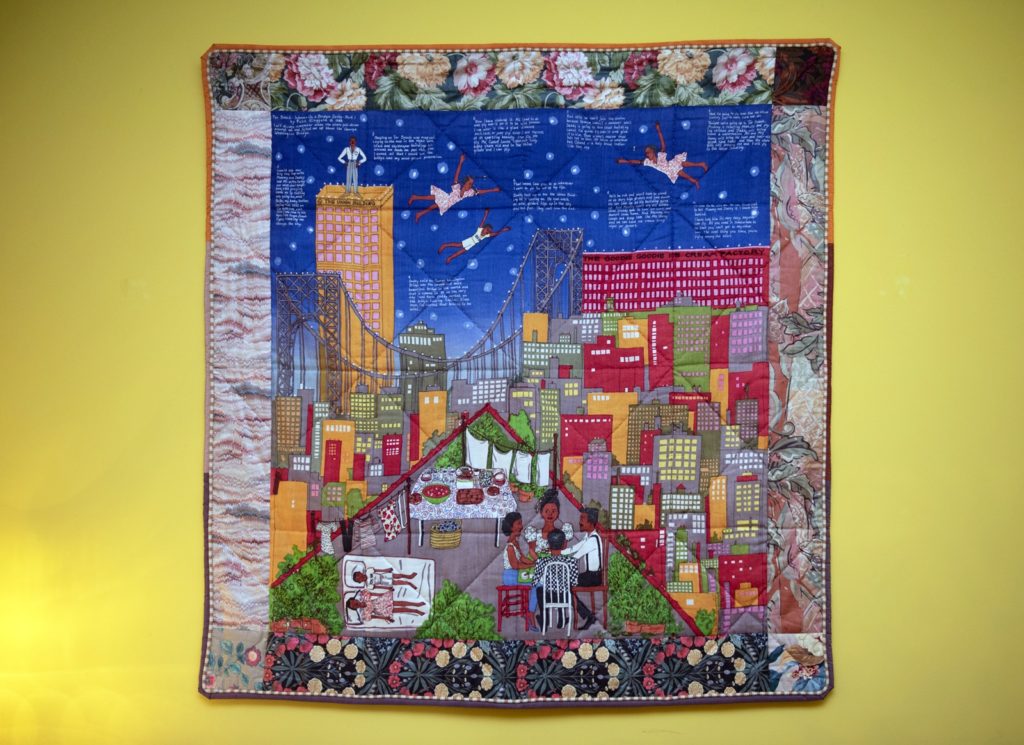

Faith Ringgold, Tar Beach II (1990). Image courtesy Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office.

A more lyrical vision of African American life appears in Faith Ringgold’s story quilt Tar Beach II (1990). This exuberant work presents New York City as a magical place where an African American family sleeps, eats, and plays cards on a Harlem rooftop during a sweltering summer evening. The city’s lights, skyscrapers, and bridges stretch out before them like a glittering tapestry as, above, the sleeping child takes to the sky in a delirious dream of freedom.

New York reappears at its most life enhancing in Dorothy Eisner’s Washington Square Park (1938), a painting centering on the Square’s famous fountain. Water erupts and cascades over children splashing in the pool while adults on the periphery enjoy the sun. Historical circumstances give the work added resonance: At the time this work was created the fountain had just been restored by Robert Moses who was simultaneously pushing to bisect the park with one of his controversial highways. As a vocal opponent of this plan, Eisner here offers an image of the conviviality that Moses’s dreams of automotive dominion would have destroyed.

Perla de Leon, Going to Work (1980). Image courtesy Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office.

The photographers in “She Persists” offer an even more direct record of a changing, multifaceted city. Consuelo Kanaga’s moody images captured New York and New Yorkers in the 1920s. Berenice Abbot recorded the changing face of the city during the 1930s, as skyscrapers sprouted and old neighborhoods were squeezed out by development. In 1979 and 1980, Perla de Leon created a body of work that explored the inhabitants and the physical deterioration of the South Bronx. In 1980, Cindy Sherman made the city the backdrop for many of her iconic Untitled Film Stills.

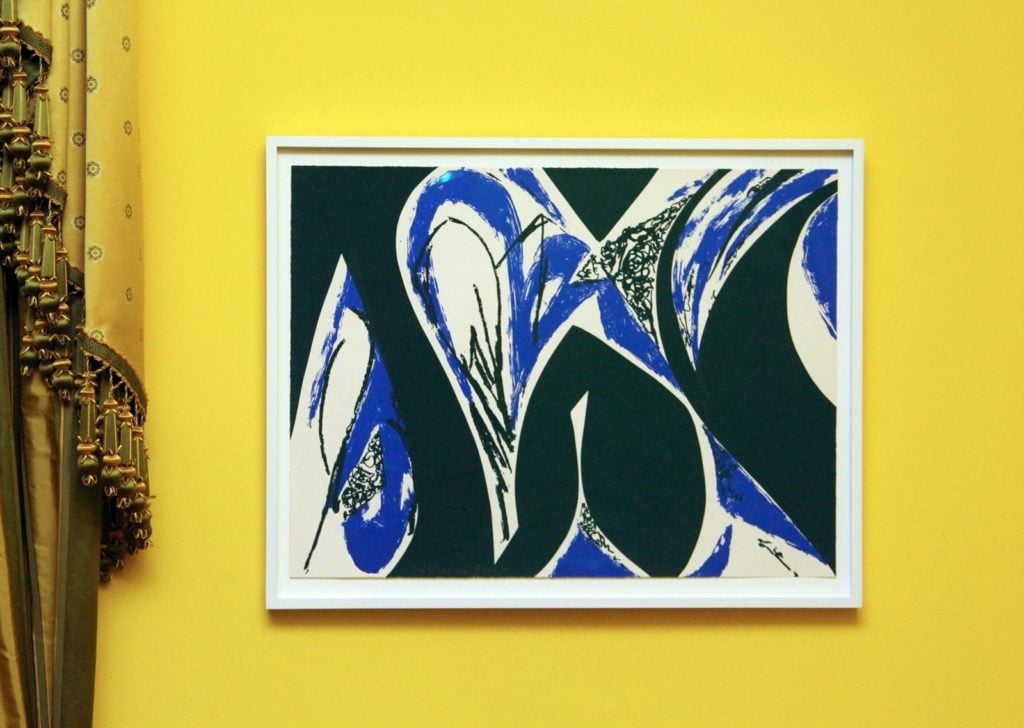

Lee Krasner, Free Space (1976). Image courtesy Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office.

The show also speaks of the history of New York through work that doesn’t specifically reference the city as subject matter. On a table in one of the rooms, a strategically placed copy of Mary Gabriel’s recent book Ninth Street Women is a reminder of the only recently canonical status of the women of Abstract Expressionism. Three of them are represented in “She Persists” by modest works: Lee Krasner, Grace Hartigan, and Helen Frankenthaler.

Betty Blayton-Taylor, Ancestors Bearing Light (2007). Image courtesy Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office.

Elsewhere, a luminous abstraction by Betty Parsons points to her other role as one of the most important art dealers during the postwar era. Two circular abstractions by Betty Blayton-Taylor are reminders of this artist who also left her mark on New York as a founding member of the Studio Museum of Harlem.

Katharine Clarissa Eileen McCray, Quashie Hand Crafted Dolls (ca. 1980). Image courtesy Michael Appleton/Mayoral Photography Office.

Along with the more conventional artworks, the show contains a number of artifacts that underscore a message of female empowerment and recognition. A homage to Shirley Chisholm, the nation’s first African American woman congressperson, takes the form of a selection of pamphlets and campaign posters. These are given added punch by a video by Mickalene Thomas (unfortunately played without sound) in which the artist digitally inserts herself into a video of one of Chisholm’s famous speeches. And in a reminder that the People’s House is also the home of New York’s First Family, the Gracie Foyer contains three charming fabric dolls made by Katherine Clarissa Eileen McCray, mother of the First Lady.

What results from the drawing together of some of New York’s best women artists in “She Persists” is a wonderfully nuanced and multifaceted picture of the city’s life and times. But the nuance shouldn’t distract from the calm, clear message that the show sends, either: A mansion created for the pleasure of a slave owner has been reimagined as the People’s House—a place to celebrate how the diversity of women artists and their struggles, setbacks, and successes have helped to make New York the iconic city that it is.

“She Persists: A Century of Women Artists in New York” is on view at Gracie Mansion, East 88th Street and East End Avenue, New York.