Art & Exhibitions

‘My Anchor Point Is Here’: How Icelandic Artist Sigurður Guðjónsson’s Venice Pavilion Is—and Isn’t—Inspired by Homeland

Guðjónsson's Venice presentation has everything and nothing to do with his native Iceland.

Guðjónsson's Venice presentation has everything and nothing to do with his native Iceland.

Vivienne Chow

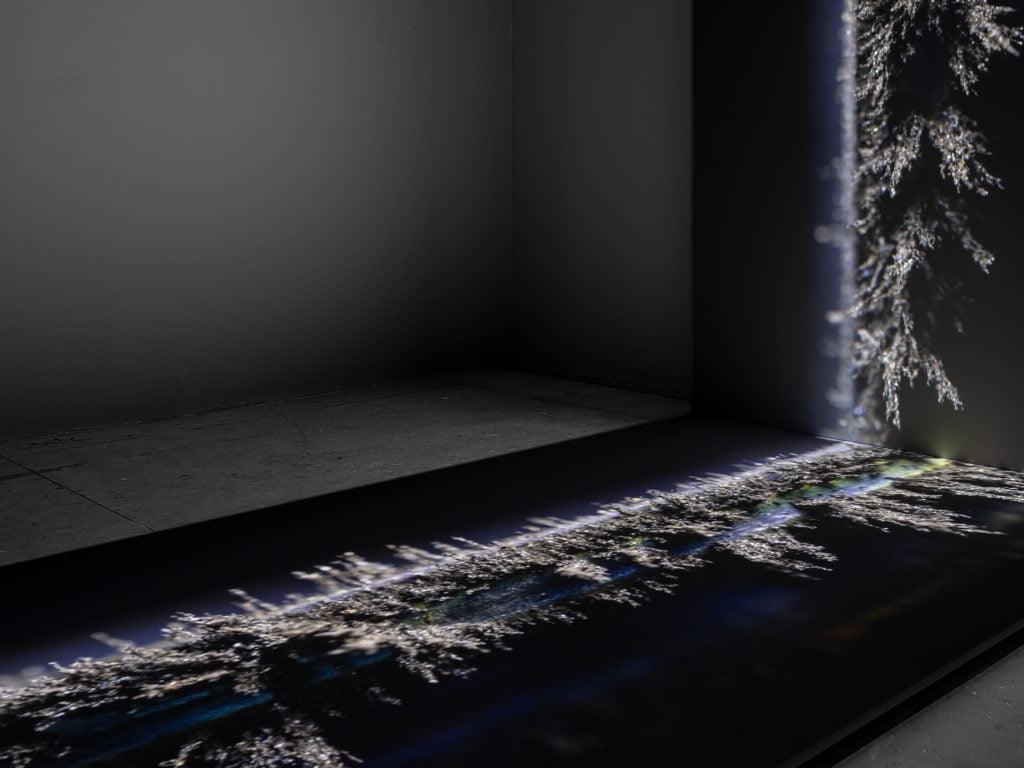

Sigurður Guðjónsson likes to keep people guessing. Take the award-winning artist’s latest offering, Perpetual Motion. At first glance, the nearly 20-foot-tall multisensory sculpture at the Icelandic pavilion at the Venice Biennale presents itself as an enigmatic, immersive, abstract audio-visual piece that transports viewers from one reality to another.

But as one watches the seemingly never-ending moving image installation, on display on perpendicular screens, one can’t help but ask: What is this exactly? And where are we headed?

“This piece will take people to thousands of directions,” Guðjónsson told Artnet News. “It’s similar to music. When you listen to music, it takes you somewhere. It is a sensory experience. It’s abstract and offers layers of readings.”

The destination varies on each viewer’s experience—as well as on their level of curiosity. The work may lead one to see it as a sculpture, a painting, or a cinematic world, the artist noted. It could also be a landscape (the most natural, yet cliched, association with anything coming from Iceland).

“Yes, we have the landscape. It’s Iceland. It always comes up,” the artist quipped.

Sigurður Guðjónsson, Installation view: Perpetual Motion, Icelandic Pavilion, 59th International Art Exhibition -– La Biennale di Venezia, 2022, Courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary, Photos: Ugo Carmeni.

Landscape, in fact, was not his mind when Guðjónsson started creating Perpetual Motion for the Icelandic pavilion, curated by Monica Bello, the curator and head of arts at CERN. The work, rather, is the result of experimentation with objects and materials.

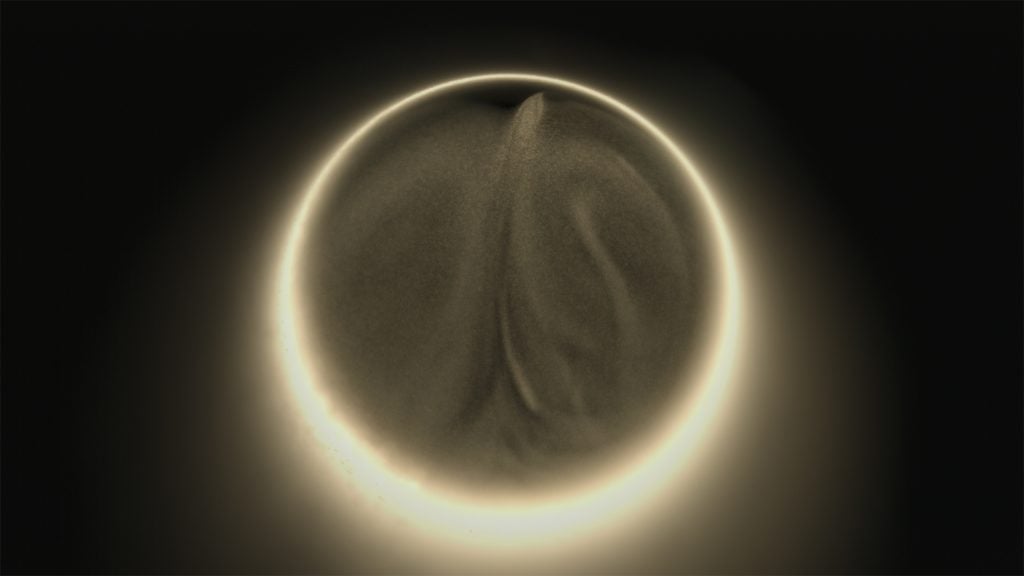

The primary object is, in fact, a small magnetic disc taken from an old loudspeaker, with metal dust sprinkled around the rim. The work depicts the metal dusted rim in extreme close up as it revolves. The outcome is a 45-minute uncut video shown on two screens connected to each other like mirror images, but their playback speeds are different. Accompanied by a visceral soundtrack developed by Guðjónsson and the famed Icelandic musician and producer Valgeir Sigurðsson, founder of the record label Bedroom Community, Perpetual Motion is a work that challenges viewers’ perceptions of materiality.

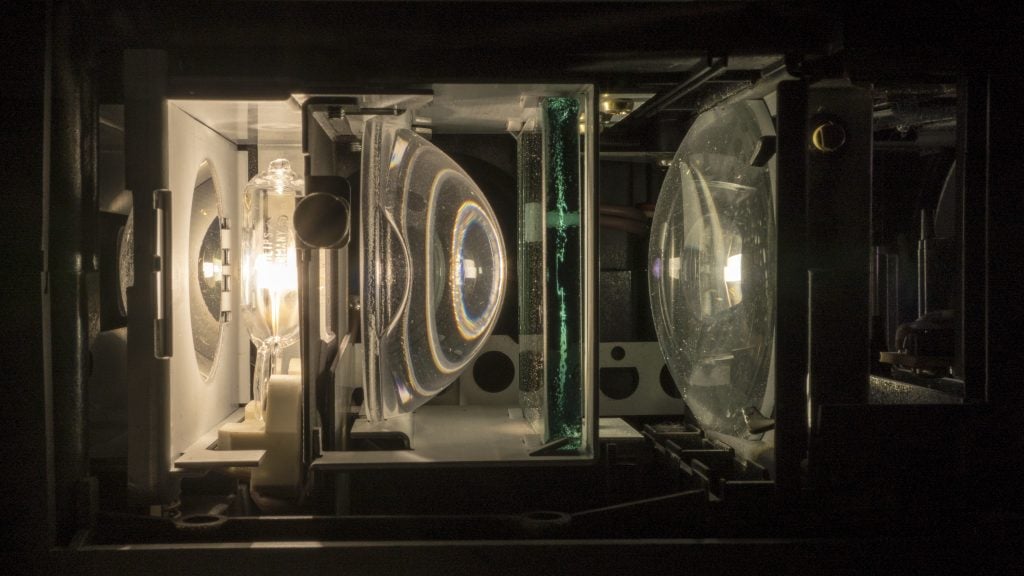

This is not the first time that Guðjónsson has played with perception by using mundane objects. For Fluorescent (2021), the artist took a peep into a fluorescent tube and presented a mesmerizing alternative view of the everyday object, exposing a hidden universe made of swirling dust. He also employed an electron microscope to scan a fragment of carbon in Enigma (2019), conjuring an otherworldly image of the material, and made the mysterious poetic space of Lightroom (2018) from an old slide projector. Tape (2016), a particularly important work for the artist, is a close-up study of a cassette tape, another medium that has been largely forgotten in the digital age.

Sigurður Guðjónsson, Still from Perpetual Motion, 2022, courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary

So what inspired Guðjónsson to get his hands on these materials and look at them differently?

“Curiosity,” he said. “I was definitely a curious kid, looking at hidden places. What’s happening inside the light? It’s a very interesting space to look into. The experiment with space and objects, and then transforming the apparatus into something new by creating many layers of perception, are all very important to me.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the unique landscape of Iceland shaped his vision.

“When you are standing in the snow but there’s a very hot spring right in front of you, you pick up the contrasting layers of smell and sound, and you sense the materials and nature differently.”

With Perpetual Motion, an extra layer of experimentation has been added: the Icelandic pavilion’s new space.

The pavilion has been nomadic since the Icelandic Art Center took over as project commissioner in 2007. Some of the presentations took place at locations far from the center of Venice, such as in a warehouse venue on the island of Giudecca in 2017 and 2019, which saw the exhibitions of Egill Sæbjörnsson, and Hrafnhildur Arnardóttir (better known as Shoplifter), respectively.

Sigurður Guðjónsson, Fluorescent (2021). Courtesy of the artist.

This time, the Icelandic pavilion is right inside the Arsenale, one of the main exhibition venues. The Icelandic Art Center estimates that the number of visitors to this year’s pavilion will be 20 times that of previous editions.

Moving to a prime location means that Guðjónsson is likely to get more exposure, as well as more pressure. “But we just have to do our best and it will work out,” he noted.

At the same time, the high-ceiling cube that allows visitors to come in and out as they move from one exhibition to another poses another dimension for his experiment.

“I was inspired by the space, the high ceiling, and the flow of the room, which influences the mood and the motion of the work,” the artist noted. “The video work is like a source to activate the space.”

Sigurður Guðjónsson, Lightroom (2018). Courtesy of the artist.

Despite its small population of just under 350,000, Iceland has been participating in Biennale since 1960. It also has a thriving music scene.

The country’s vibrant cultural landscape drew the attention of Barbara Kerr, a psychology professor at the University of Kansas who led a 2017 study to investigate why Iceland is so creative.

The study concluded that family structures and education in the country lay the foundation for creative processes. Interviewees quoted in the study pointed to the built environment of the city as a factor of creative productivity: besides art museums, galleries, and art spaces in the capital city of Reykjavik, the small but elegant contemporary art space LÁ Art Museum can be found in Hveragerði, a town with a population of less than 3,000 people.

The ever-changing weather and storied landscape of Iceland, however, did not play such a conscious role in influencing artists’ creations, according to Kerr’s findings.

The magnificent landscape of Iceland. Photo: Vivienne Chow.

Guðjónsson, who was born in 1975, built his career against such a backdrop. He studied at the Iceland University of the Arts between 2000 and 2003, followed by a year at the Akademie Der Bildenden Kunste in Vienna.

“It’s a very local, small art scene,” he said of Iceland. “I like being here but it’s very important for us to get a broad perspective—it’s extremely important to get away.”

Such a strong desire to leave and return is prominent among Icelandic artists, who have a strong presence internationally, said Ingibjörg Jónsdóttir, director and founder of the Berg Contemporary art gallery, which represents Guðjónsson. The landscape and nature are there, she said, but much more deeply embedded in artists’ psyche.

“[Iceland] is not stagnant like other places. A small society has a need to connect with others. It is far from the continent, but it is right between Europe and America. There’s a connection with the mainstream, international environment of art. Over the years, artists have the opportunity to study abroad, and when they return, they bring something back,” said Jónsdóttir, whose gallery recently presented Guðjónsson’s work in London ahead of the Venice presentation.

Sigurður Guðjónsson, Installation view: Perpetual Motion, Icelandic Pavilion, 59th International Art Exhibition -– La Biennale di Venezia, 2022, Courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary, Photos: Ugo Carmeni.

As for Guðjónsson, he has big plans upon his return to Iceland, where he will release a book chronicling his journey over the past decade. He will also be teaming up with composer Anna Þorvaldsdóttir and multi-Grammy-nominated artists the Spektral Quartet for a performance of his work Enigma at the Reykjavík Arts Festival in June, followed by a major solo show at the Reykjavík Art Museum in October, coinciding with a presentation of Perpetual Motion at Berg Contemporary for a home audience.

He may have plans to experiment with a prolonged period of time away from home, but he has no plans to permanently relocate.

“My anchor point is here,” he said.