In 1991, the city of Detroit demolished a row of houses that were part of the Heidelberg Project, an outdoor art installation that converted buildings into living sculptures and an entire street into such an explosion of found objects that it looked like a sprawling outdoor attic.

When real-estate developer and art collector Gilbert Silverman heard the news, he promptly drove over in his Mercedes 350 to give its founder Tyree Guyton a check for $3,000 to support the rebuilding effort. Guyton grew up on Heidelberg Street.

With the artworks he’d saved from destruction (and Silverman’s money), Guyton set out to again transform two blocks, including where his childhood home still stood, into something filled with life. Guyton assembled installations out of toys, old appliances, and other everyday items that the families who’d once resided there—the mostly Black families—had left behind. The neighborhood was near shambles: One of the first houses Guyton had taken over back in 1986 was being used as a crack house.

After Silverman gave Guyton the money, the artist asked if he wanted a work of art in exchange—something he could actually display at home. In response, Jenenne Whitfield, Guyton’s wife, remembered Silverman saying: “I’ll get something eventually, just keep doing your work.”

Two years later, Whitfield took over as executive director of the Heidelberg Project, and her 30-year fundraising effort offers a microcosm of the two ways in which artists leverage the art market to fund their community projects.

On the one hand, Whitfield would promote Guyton’s work to collectors of his studio practice (then redirected 25 to 50 percent of the proceeds back to the project). Before long, it became a known fact, if not a feel-good selling point, that “by purchasing Tyree’s work,” she said, “they were also investing in the community.”

A view of the Heidelberg Project. Courtesy of the Heidelberg Project Archives.

But the real power she generated in that time was using Guyton’s profile as an artist to cultivate “a lot of Gil Silvermans,” she said. Ultimately, she estimated that “65 to 70 percent of the work became funded by those kinds of relationships.” Some collectors turned patrons also sat on the boards of major foundations, which opened up another path to fundraising.

When it comes to artist-driven community work, private versus grant funding isn’t an either-or proposition. Using the art market “is not just about making sales,” said artist Edgar Arceneaux, “it’s in the associated power that comes from leveraging relationships inside it.”

The 2022 Burns Halperin Report shows that mainstream art museums and the auction market do not accurately reflect the contributions of women and Black artists. And while the reasons for that can largely be boiled down to bias, some of these artists are consciously choosing to divert their spoils away from established systems in order to build new ones that are more directly rooted in their own communities.

Artists like Guyton and Arcenaux lack some trappings of traditional art-world success; they have few, if any, auction sales to their name and represent a small handful of acquisitions among the 31 institutions surveyed by the Burns-Halperin Report.

But for them, getting a collector to donate their work to a big-name museum is less important than getting them to fund their own community oriented or “social practice” art projects. And they have become adept at leveraging the system to make it happen.

Artist Augustin Aguirre walks in front of a tiled wall he made as part of the Watts House Project redevelopment across the street from the Watts Towers. (Photo by Bob Chamberlin/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Can the Market Separate the Art From the Artist?

Edgar Arceneaux is familiar with this strategy. He employed it for 13 years as head of the Watts House Project.

Arceneaux inherited the project in 1999 from another artist, Rick Lowe, whose name has since become synonymous with social practice art. The Watts House Project was an L.A. outgrowth of Lowe’s Project Row Houses, a series of buildings converted into studios, exhibition spaces, and housing for young mothers in Houston.

After three years working with Arceneaux to rehab houses near the Watts Towers, Lowe gave him the remaining few thousand dollars in grant money he’d raised and wished him luck. When that money ran out, the project stalled. Arceneaux “understood pretty quickly that to build any cachet,” he said, “it had to be through the art market”—a sphere he defines broadly as the art industry and art-world system.

So as he nurtured his traditional art practice and landed big shows (including a coveted spot in the Whitney Biennial), he would talk about Watts—to anyone who would listen. Around 2008, he had a breakthrough. A curator he’d worked with at the Hammer Museum helped Arceneaux procure a grant for $35,000. And in what seemed like the flip of a switch, the art world started to “take me seriously,” he said. More money started rolling in. Hundreds of thousands of dollars—in a matter of three years.

Artist Alexandra Grant got involved in the project around then. For funding, she and other artists would “use our careers to leverage these grants, that were personal artist grants,” she explained, “and that were for placemaking.” In other words, Grant and her peers learned to market themselves and leverage their stature inside the art-world system to help get grants designed for personal artist projects—that they’d then apply to these broader social impact initiatives.

AMBOS’s America’s Wall (2018). Photo by Gina Clyne

It’s All Marketing

Tanya Aguiñiga’s practice covers a lot of traditional ground—sculpture, furniture design, site-specific installation. But Aguiniga’s collectors know that “through supporting the efforts of what the studio produces,” she explained, “we’re able to channel money into these other more important humanitarian projects.”

Most of those are done through AMBOS (Art Made Between Opposite), her project to use her skills to impact work in Tijuana, which she founded after receiving a grant from Creative Capital in 2016.

Aguiñiga started going to Tijuana when she was still a teenager to collaborate with the Border Art Workshop—an organization that, since 1984, had been using art to bring attention to issues faced by border communities. One of its projects was helping “co-build and run a community center on the outskirts of [Tijuana],” she explained, “that was run by women and made out of trash from the U.S.”

At the beginning of Aguiñiga’s humanitarian work in Tijuana, “social practice wasn’t really a term,” she noted. That classification started being applied to the type of projects she was doing in the early aughts. Aguiñiga then realized she shouldn’t “keep everything separate,” she continued, “and that people need to understand that it’s all one thing, reflecting the larger ethos of the studio.”

An AMBOS project, Border Quipu (2016–2018). Photo by Gina Clyne

The Superstar Effect, Renewed

As the art world put a name to what these artists were doing, Arceneaux noticed that “because our main source of funding came from the visual art world,” that paradigm “needed a figurehead as a way to raise additional resources.”

This created a new complexity: replicating the superstar system that governs both the art market and, to some extent, the museum system, without sacrificing the integrity of community-oriented work.

Artists can use their broad marketability to generate support for a project, but they must be careful when they become the product, Grant said. “People would pursue a community-based project and, two years or something after, it’s just all this money was in this old swingset thing or whatever,” she noted. “It never actually affected the community.”

“How do we ask what the community wants,” she continued, “and then be able to step away and have it exist—without it being about just building the career of the artist?”

The disconnect between the art world and communities in need can feel to artists—and especially social practice artists—like they’re constantly “in an elevator that goes between the penthouse and the basement,” Grant said,

She addresses that by developing and selling products in support of community organizations through her grantLOVE project.

For artists who help their own community initiatives, “the role they play in drawing attention to something—introducing friends and connecting people—is very, very valuable in that they are introducing people who are genuinely interested in supporting people,” she continued, but “they are also at such a high remove from the ground of these vital projects.”

Alexandra Grant signing works at RISK’s studio in 2016.

The Next Generation

Watts House Project ended in 2014, but its legacy didn’t.

New generations of artists are emerging and applying lessons of the initiatives that came before them. There’s Theaster Gates’s Rebuild Foundation, a development initiative rehabbing buildings in Chicago’s South Side, and Lauren Halsey’s Summaeverythang, which started distributing fresh food to residents in South Central Los Angeles during the pandemic.

“Every misstep that Watts House Project made,” Grant said, fellow Los Angeles artist Mark Bradford “used to make sure he didn’t make the same mistakes.”

It costs roughly $1 million per year to run Art + Practice, the non profit arts space that Bradford cofounded nearly a decade ago, getting things started with a portion of his “genius” grant money from the MacArthur Foundation. The foundation provides free, museum-quality exhibitions and programming—very literally, through its partnership with local institutions, like the Hammer Museum and the California African American Museum—to a Black neighborhood in L.A.

Meanwhile, Halsey’s Summaeverythang has grown so much—and so fast—that Halsey has plans to turn it into a full-fledged community center. She told the Creative Independent that “outside of form, my sculpture practice is about trying to create as many funding opportunities for the community center as possible.”

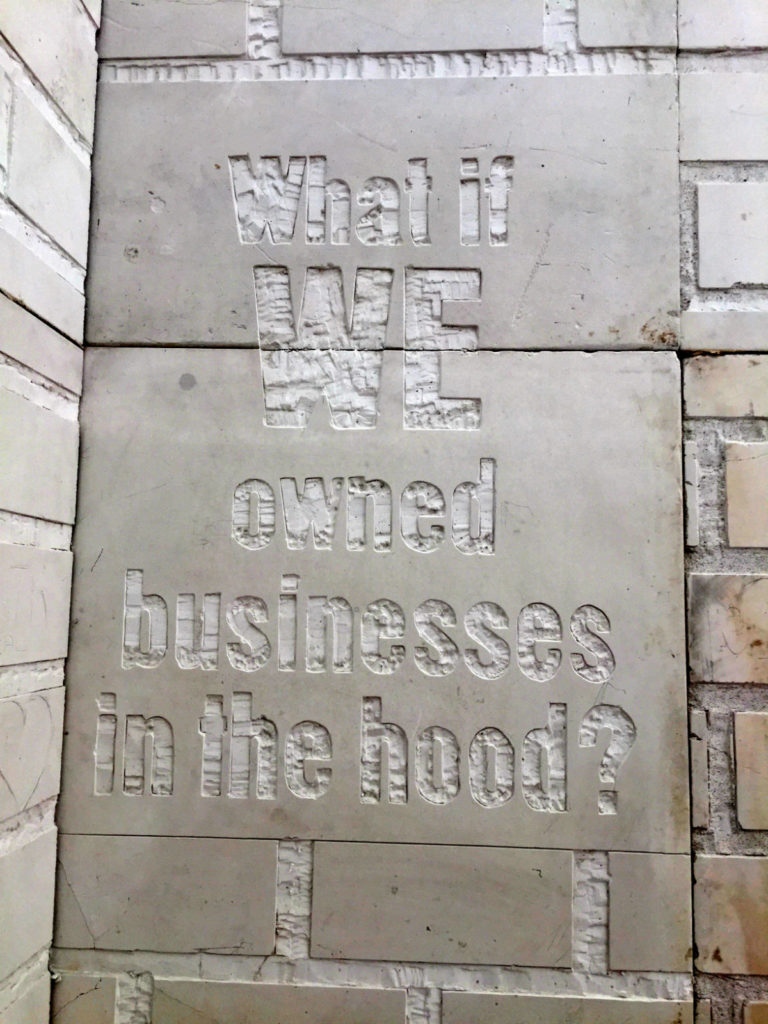

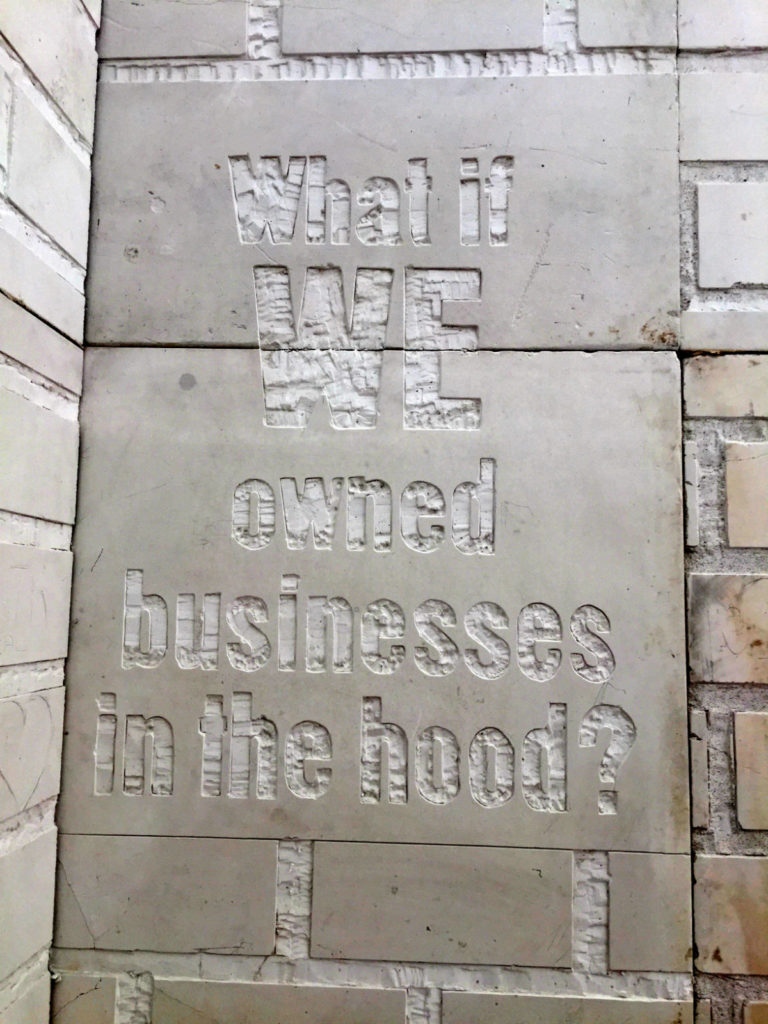

Lauren Halsey, Detail, The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (2018). Photo: Colony Little.

“I think that Lauren is the next generation,” Grant said. “She’s not only looked, probably, at Watts House Project, but she also looked at Art and Practice, as well.”

Artist Titus Kaphar’s community, in the predominantly Black Dixwell, Connecticut, also benefits from him using his rising profile in the art world—as a MacArthur fellow, and top-selling auction and Gagosian-represented artist—to raise money for NXTHVN, the nonprofit arts hub he cofounded there in 2017. To build the space alone cost around ten million dollars, which Kaphar and his partners procured through grants and private investments.

So it’s all good will. Explicitly or not. And it’s also: all the art market.

You can read all the articles in the 2022 Burns Halperin Report here.