Can you solve this art historical riddle?

A woman moves into a new home. Beneath a swath of drywall in the living room is a work by one of the most important artists of the 21st century. But even if she uncovers it, the mural is worthless. Can you guess the artist?

The answer: Sol LeWitt.

It might sound like a theoretical brain tease, but this scenario is actually playing out right now in Houston, Texas, where a family’s decision to uncover a hidden drawing has become a vivid illustration of the definition of conceptual art.

But not everyone is pleased about the project.

Walling Over LeWitt

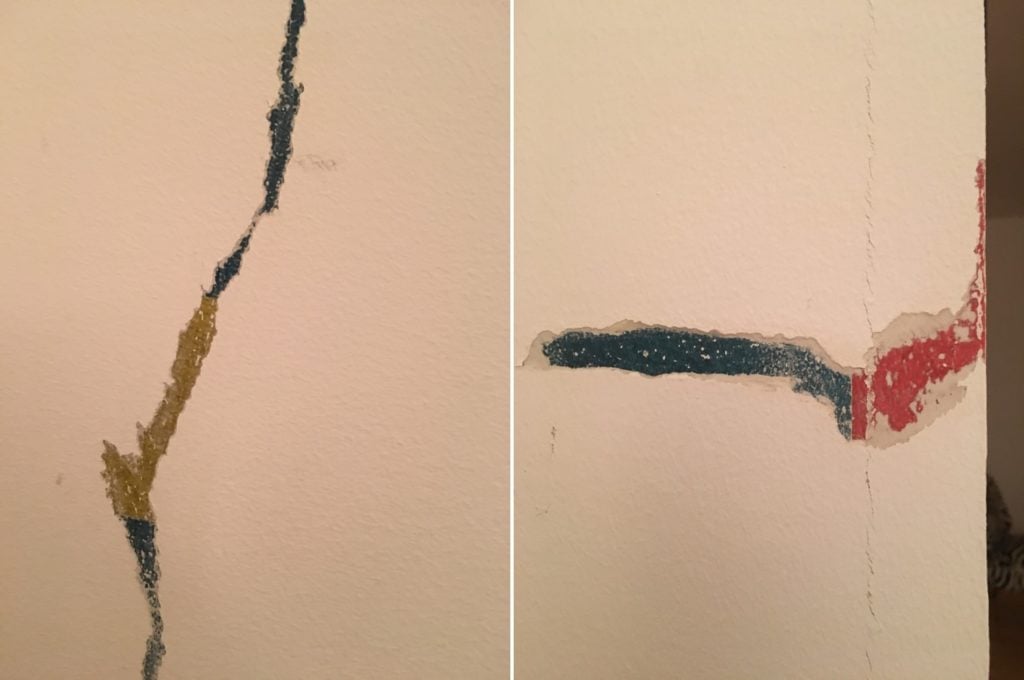

The story began in 2013, when the architect William Stern died and left his home and art holdings to the Menil Collection in Houston. Among the works was Wall Drawing #679 (1991), a wall-engulfing blue mural with yellow and red intersecting lines that LeWitt created specifically for Stern’s living room.

The Menil Collection decided to keep Stern’s art, but sold the home to a local dentist in 2014. Before she moved in, the museum had the vibrant artwork painted over.

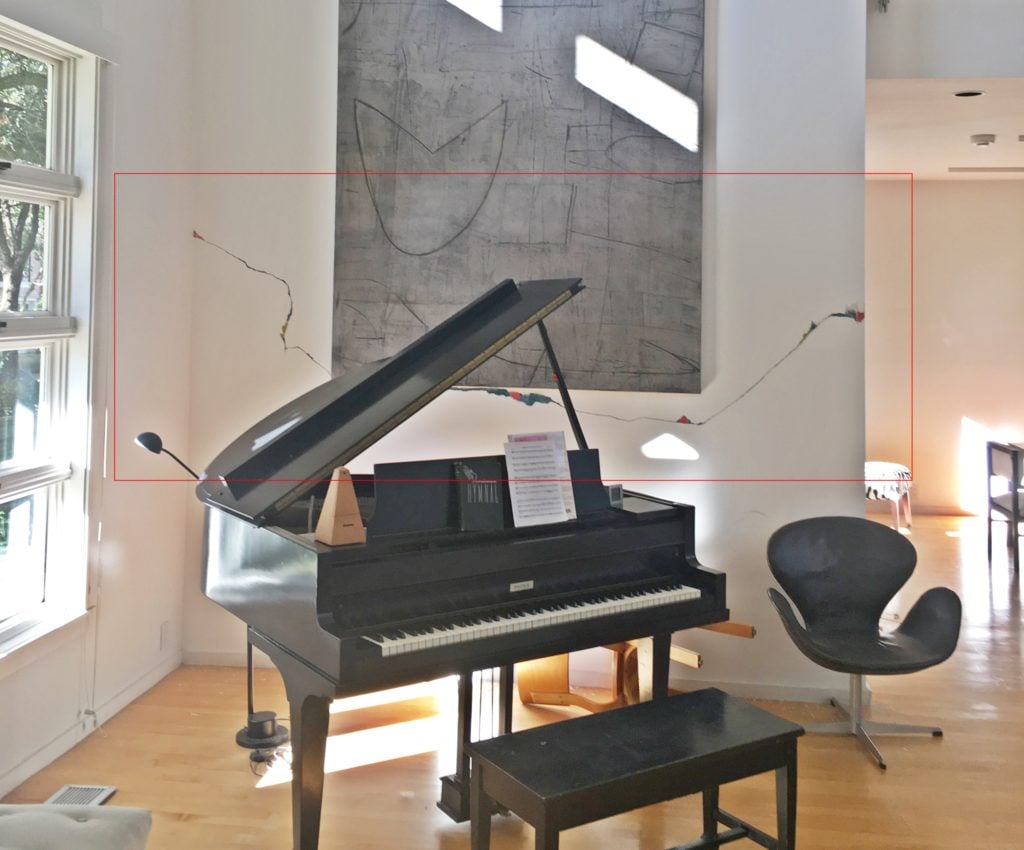

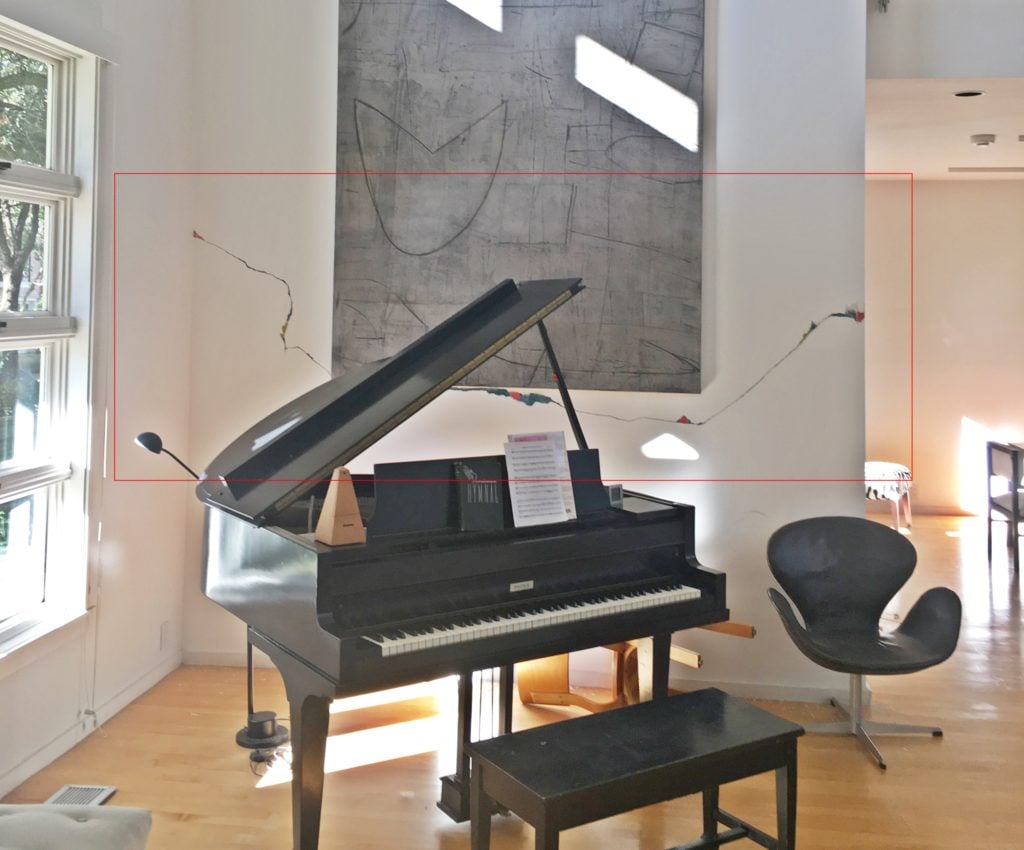

The main wall of the William Stern House in Houston, Texas. Image courtesy of Jonna Hitchcock.

“When we ceased to own the wall and the house it previously existed in, and could no longer be in control of its environment, it was painted over and its physical life came to an end,” a spokesman for the Menil Collection explained to artnet News. “This was always the intent of the artist, and is the standard procedure when these works change ownership.” Although the museum has not reconstructed the piece since it entered the collection, “it still exists as a concept and idea.”

Indeed, this moment illustrates conceptual art in action: The certificate of authenticity and instructions for how to execute the work constitute the wall drawing, rather than the physical paint itself. When the Menil covered up the wall, what lay beneath ceased to be a work of Sol LeWitt.

Un-Erasing the Past

That fact, however, hasn’t stopped the homeowner’s daughter, Jonna Hitchcock, from seeking to uncover the original design. Hitchcock says she and her mother always knew the LeWitt work was sitting right beneath the white wall. But they had not dared to go digging for it. That changed when a friend who was visiting “had the courage to go over and scrape a bit,” she says.

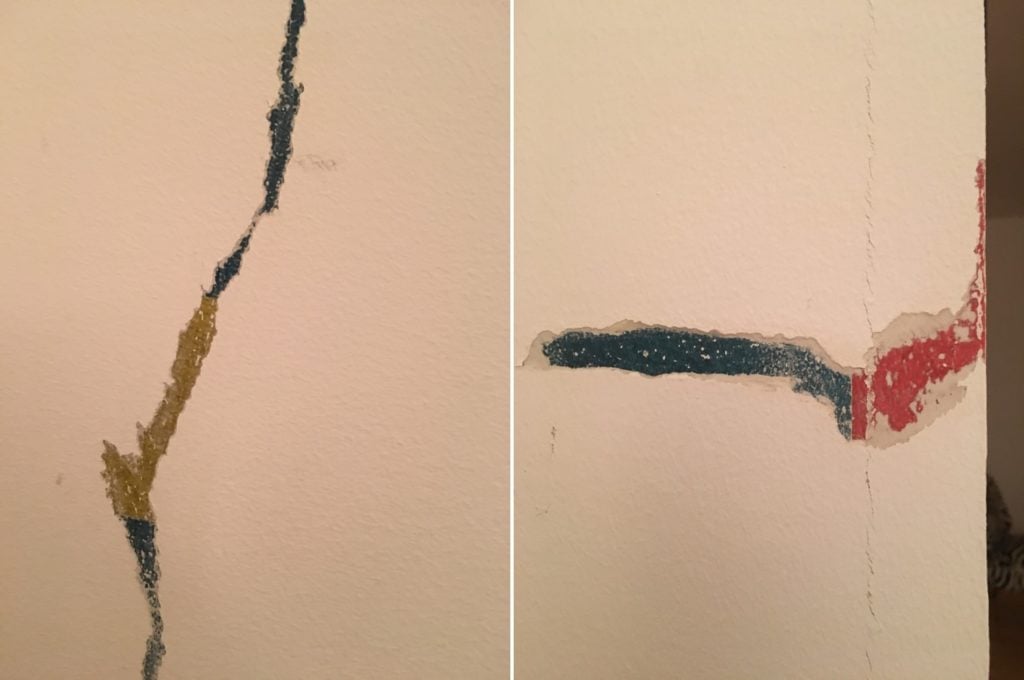

To the family’s surprise, they found that the original drawing was covered not by paint, but simply by a layer of sheetrock, which came off easily when moistened. Hitchcock decided to embrace the opportunity and document the process of unearthing the drawing through a documentary and on a website she has called Un-Erasing Sol LeWitt.

Indeed, Hitchcock considers the whole process a kind of conceptual art project of her own: The name of the blog is a nod to Robert Rauschenberg’s famous work, Erased de Kooning Drawing.

Detail of the partially uncovered Sol Lewitt drawing (framed by red square). Image courtesy of Jonna Hitchcock.

“I hope our project brings more attention and understanding of what conceptual art is all about,” she tells artnet News.

Debate Ensues

Hitchcock reached out to the LeWitt estate and the Menil Collection to alert them of her plans, but says they have not communicated with her directly about it. (A representative for the estate did not immediately respond to a request for comment.)

So far, the Menil seems to be begrudgingly tolerating the project. A spokesman for the collection told artnet News that “the homeowner may certainly do whatever projects they wish to undertake in their home.” But he also took care to clarify that what they are uncovering is not, in fact, a work by Sol LeWitt.

Hitchcock says she understands that—up to a point. Although she was not privy to the agreement between Stern and the Menil, she says that conversations with Stern’s former colleagues and friends have led her to believe that the architect would have wanted the museum to keep the house and present the LeWitt in the space for which it was designed.

Detail images of the partially uncovered Sol Lewitt drawing. Images courtesy of Jonna Hitchcock.

“This drawing was site-specific and unlike most LeWitt drawings, it wasn’t designed to be temporary—it was inked again 10 years after the first execution,” she says.

A Stern Dissent

Roy Nolen, the executor of William Stern’s estate, disagrees. In a statement to artnet News, he says that “Bill Stern intended that the installation of the wall drawing in his house was to be terminated, and that the Menil was to own the wall drawing, with the right to install it whenever and wherever it chooses.” He notes that he and Stern had many conversations about the collection in the weeks before his death and “specifically discussed which techniques the staff of the Menil might employ to ‘remove’ the LeWitt wall drawing from the house.”

“I am quite certain that he would feel that his legacy and reputation were being exploited for personal gain by the so-called ‘unerasing’ documentary proposed by representatives of the current owner of the house he built and loved,” Nolen says. (Hitchcock calls the notion that she or her mother are motivated by personal gain “preposterous.”)

Architect Bill Stern. Photo courtesy of Stern and Bucek Architects.

Hitchcock is now consulting local conservators and artists about how best to proceed to uncover the work safely. Is she concerned that the museum or estate might eventually ask her to abandon her quest?

“A month ago, my mother had a plain white wall in a house that she loved,” Hitchcock says. “And the worst thing that could happen is if by some unforeseen legal loophole someone compels us to cover it back up.”

Then again, she notes, her project is unlikely to set a problematic precedent. “It’s not like everyone is going to start chipping away to find their Sol LeWitt now,” she says. “It’s a pretty unique situation.”