Art History

Across the U.S., Museums Are Exploring Spiritualism and the Occult as Powerful, Unsung Forces in Art History

"Another World" and "Supernatural America" offer a chance to reconsider the politics of long-derided cultural movements.

"Another World" and "Supernatural America" offer a chance to reconsider the politics of long-derided cultural movements.

Eleanor Heartney

In art circles, spirituality is coming out of closet as curators and critics reconsider the influence of religion on artists from Robert Smithson to Andy Warhol. But spirituality’s cousins, spiritualism and the occult, remain cloaked with suspicion. There is now, as there long has been, an aura of disrepute around these practices: they reek of charlatanism, crackpot science, and New Age gullibility. A few years ago, when I was writing an article on art and spirituality, I was warned by a prominent writer on the subject to avoid the word spiritualism. And indeed, when major art museums touch on the subject of spiritualism or the occult, it is generally to debunk or satirize. The 2018 Hilma af Klint exhibition at the Guggenheim was the rare exception, but even there the curators seemed discomfited by the artist’s insistence that her works should be seen as messages from her spirit guides.

Two exhibitions currently on view take spiritualism and the occult seriously, examining not only works made by artists in touch with other realities, but also the way that such explorations are woven into the fabric of American art and culture. Both exhibitions have extensive, well-researched catalogues that make their cases even to those of us unable or unwilling to travel in the time of Covid, and are well worth engaging with.

First some definitions: While spirituality has evolved into an all-purpose term encompassing myriad anti-materialistic approaches to art, spiritualism has a specific meaning. It flowered in the 19th century as a religious movement aimed at proving the immortality of the soul by establishing communication with spirits of the dead. The occult encompasses a wider group of practices, spiritualism among them, based on the belief that secret or hidden knowledge can give access to otherworldly or magical energies.

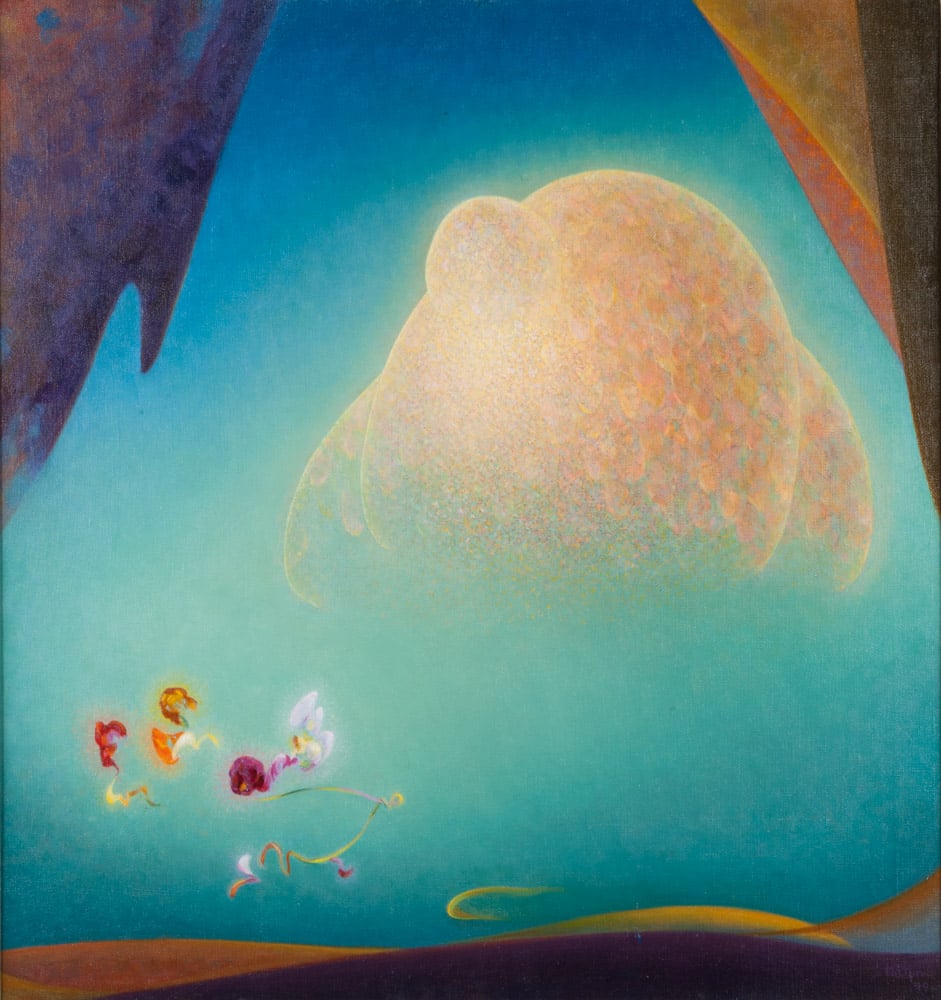

Agnes Pelton, Nurture (1940). Collection of the Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University, gift of the Marie Eccles Caine Foundation.

“Another World,” which opened in October at the Philbrook Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, resuscitates the Transcendental Painting Group, a Southwest-based collective that emerged in 1930s New Mexico. As one of its adherents explained, its members were seeking “a richer and deeper land—the world of peace—love and human relations projected through pure form.”

These artists drew heavily on the occult philosophy of Theosophy and explored such phenomena as synesthesia, vibration, sacred geometry, and cosmic images in their quest to reach a transcendent state of consciousness. As curator Michael Duncan explains, they adopted the name Transcendental, not from Emerson’s fusion of nature and the divine, but from the quest to discover the inner spiritual depths within each artist.

Today the best-known member of TPG is Agnes Pelton, the subject of a dazzling 2020 exhibition at the Whitney Museum. The others are virtually unknown outside New Mexico, where all but the Southern California-based Pelton lived. TPG existed as a group for only three years before being disrupted by the advent of the Second World War. But the artists continued to work individually for decades after.

Raymond Jonson, Casein Tempera No. 1 (1939).

Albuquerque Museum, gift of Rose Silva and Evelyn Gutierrez.

Stylistically, they present diverse approaches to transcendence, ranging from the crisp, precisionist geometry of Raymond Jonson and the almost-landscapes of Lawren Harris to the Zen-inspired improvisations of William Lumpkins and the gentle biomorphism of Florence Miller Pierce.

Duncan argues that TPG’s invisibility is a result of “the double disadvantage of being an openly spiritual movement from the wrong side of the Mississippi.” Until recently, art historians have shown great reluctance to acknowledge the overwhelming evidence of the influence of occult ideas on the development of modernism. As the canon splinters, the paintings in “Another World” open up new avenues for understanding the evolution of American abstraction, especially as it took place outside the major centers of the mid-century American art world.

Lawren Harris, Painting No. 4 (ca. 1939). Collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

While TPG’s rhetoric of inner Godhood and the archaic Unconscious may still raise eyebrows, the works fit comfortably in the art historical space currently being opened up by the huge public response to the Hilma af Klint show. “Supernatural America: the Paranormal in American Art” presents a thornier challenge.

This exhibition—opening at the Minneapolis Institute of Art after travels to Toledo and Louisville—has been curated by the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s Robert Cozzolino, who reports that he personally has had other-worldly experiences. Rather than the easier-to-digest influence of occultism on abstraction, Cozzolino has chosen to emphasize its manifestations as they occur in figurative art. He follows these through the whole swath of American history employing a definition of the paranormal that encompasses everything from séances and spirit photography to mesmerism and UFOs.

Gertrude Abercrombie, Search for Rest (1951). Collection of Sandra and Bram Dijkstra. Photo: Sandy and Bram Dijkstra.

As set out in the catalogue, the historical record includes some fascinating case studies. For instance, there’s the story of Gertrude Abercrombie, painter and self-described witch whose works represent herself as an elongated figure who levitates, drifts through sparse landscapes, or consorts with her animal “familiars” in spooky domestic interiors. An essentially unschooled artist who was an aficionado of the prewar Chicago jazz scene, Abercrombie created eerie works that seem born of a rebellion against the strictures of conventional marriage and motherhood.

Representing another form of rebellion, we meet the elegant Lady Campbell, a British aristocrat, cross-dresser, actress, and spiritualist. She served as inspiration for one of Whistler’s most ethereal paintings, a representation of a woman’s face and hands emerging mysteriously from an enveloping darkness, which was lauded as a spiritualist icon. The Minneapolis show also introduces Wilson Bentley whose obsessive photographs of vanishing snowflakes are seen here as part of a post-Civil War hangover, with the ephemeral crystals providing a metaphor for the flickering essence of the souls of fallen soldiers.

When it comes to contemporary art, the exhibition casts a wide net. Several artists take inspiration from historical manifestations of the occult. The late Jeremy Blake’s 2002 video Winchester is an impressionistic tour of the ghost haunted Winchester mansion in San Jose California that was home to the eccentric widow of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. Rachel Rose’s Wil-o-Wisp evokes the life of 17th century mystic Elspeth Blake who was persecuted for her practice of magic and healing.

But especially fascinating are works by artists who themselves have had occult experiences. Cozzolino’s introductory essay opens with a discussion of a set of early works by painter Jack Whitten. These comprised spectral images that the artist felt had emerged unbidden from early memories of ghost stories surrounding a lynching in his father’s Mississippi hometown. The works are not reproduced in the catalogue, Cozzolino notes, because Whitten’s gallery doesn’t want his work associated with spiritualism. But as described, they would seem to bear a striking resemblance to late 19th-century practice of thought photography which purported to provide records of their subject’s thought as transmitted by energy waves directly from the brain.

Cozzolino quotes a statement by Whitten: “I LIKE THE NOTION OF PAINTING AS OBJECT USED TO SEDUCE SPIRIT.” And, indeed, the exhibition as a whole suggests a connection between African American folk knowledge, African religious practices, and the profound sympathy for the supernatural found in the work of many African American artists.

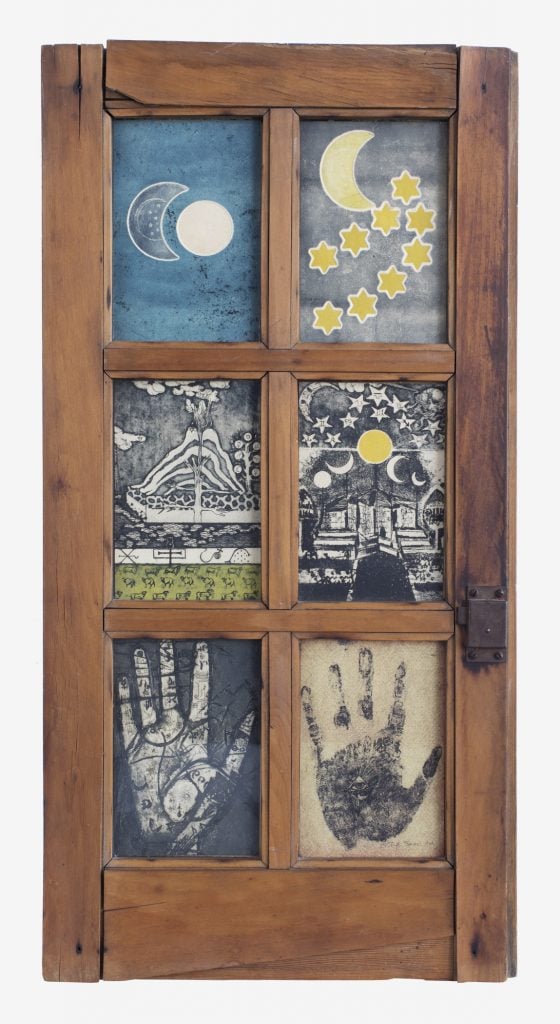

Betye Saar, The View from the Sorcerer’s Window (1966). Collection of halley k harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld. Photo: Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY. Courtesy the Artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, CA. © Betye Saar.

Some cases in point: Howardina Pindell evokes the spirit-haunted Middle Passage where so many captives perished on their way to slavery, while Ellen Gallagher imagines the mythical land of Drexciya said to be populated by aquatic beings born from the pregnant women thrown overboard from slave ships. Whitfield Lovell’s Visitation: The Richmond Project conjures the ghosts of the residents of post-Civil War America’s first successful Black entrepreneurial neighborhood. Works by Betye and Allison Saar explore the tradition of “conjur women,” those herbalists and healers in rural southern communities who are said to traffic in both black and white magic. The catalogue of “Supernatural America” also gives substantial space to Renee Stout’s The Rootworker’s Worktable, an installation that presents the artist’s version of one such herbalist’s tools for gaining access to the spiritual world.

Contemporary African American artists are not alone in their openness to the occult. “Supernatural America” makes a point of presenting works from groups often marginalized by mainstream American culture, among them Native Americans, self taught and outsider artists, UFO abductees, psychics, and witches. In this vein, it also provides a mystical context for works by feminist artists like Carolee Schneemann, Mary Beth Edelson, and Ana Mendieta. An essay on their practices suggests that feminist art history shares the culture’s general squeamishness about spiritual matters, leading it to downplay the tremendous interest shown by ‘70s feminists in ritual, Great Goddess archetypes, and the sacred feminine.

Renée Stout, <em?The Rootworker’s Worktable (2011). Karen and Robert Duncan Collection, Lincoln NE. Photo: Renée Stout.

The selections in “Supernatural America” emphasize progressive aspects of the occult impulse. This is in keeping with the historical record. In the 19th century, spiritualism, in particular, belonged to a constellation of interests that included abolition, women’s rights, socialism, temperance, and other social reforms.

William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of The Liberator, the foremost abolitionist newspaper, was an avid Spiritualist. Mary Todd Lincoln conducted séances in the White House. In their monumental History of Woman Suffrage, pioneering feminists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton declared, “The only religious sect in the world… that has recognized the equality of women is the Spiritualists.” Historian Ann Braude argues that spiritualists and social reformers shared a radical individualism based on resistance to hierarchies and enforced orthodoxies. She maintains, “The religious anarchism of spiritualism provided a positive religious expression that harmonized with the extreme individualism of radical reform.”

However, Braude notes that contemporary narratives of the struggle for women’s rights have largely erased the spiritualists’ contribution. The same is true for accounts of abolition. The suppression of these histories have contributed to the occult’s bad odor—especially at a time when skepticism and individualism have taken a reactionary turn, manifesting themselves in the anti-vax movement and the proliferation of conspiracy theories around the belief that Bill Gates plans to insert micro chips into our brains.

Indeed, you could say that the decoupling of spiritualism and the occult from the history of progressive ideas mirrors their decoupling from the history of art. But as the utopian dreams of groups like TPG and the individualistic quests of the outsiders in “Supernatural America” demonstrate, the occult is deeply entwined with American art and identity.

It is often said that belief in mysticism, occult energies, and immaterial realities grows stronger in times of trauma. It is easy today to scoff at the obvious fraudulence of some 19th century spirit manifestations. But during that time of social, political, and philosophical upheaval, there was a widespread tendency to spiritualize such emerging technologies as the photograph, the telegraph, and electromagnetism. Today, many of our own emerging sciences, from Artificial Intelligence to the study of dark matter to the renewed attention to the therapeutic properties of psilocybin, again demonstrate that the line between science and “pseudo science” can be difficult to draw.

In times of multiple crises, settled certainties become undone. “Another World” and “Supernatural America” suggest how artists can help us look beyond the world we only think we know.