The Hammer

Simon de Pury on How the Photographic Medium Will Survive the Proliferation of NFTs and Moving Image Work

The auctioneer reflects on the perennial appeal of the still image.

The auctioneer reflects on the perennial appeal of the still image.

Simon de Pury

Every month in The Hammer, art-industry veteran Simon de Pury lifts the curtain on his life as the ultimate art-world insider, his brushes with celebrity, and his invaluable insight into the inner workings of the art market.

It is now nearly two hundred years ago, in 1826, that French scientist Joseph Nicéphore Niépce took what is considered the earliest photograph to survive. (I won’t go into the mythology of the Turin shroud that was first mentioned in 1354, and was meant to show the image of Christ’s head in the negative). Through the 19th and 20th century, photography conquered the world and became omnipresent. The artistic vision of some of the world’s most talented photographers was being admired thanks to the exposure it got in newspapers, magazines, but also books and exhibtions.

After Niépce, however, it took 150 years for photography to begin being accepted as something that was worthwhile collecting. Sotheby’s and Christie’s started organizing photography auctions in the early 1970s. I still vividly remember some of the comments being made at the time. “Why spend money on acquiring a photograph that its author could infinitely reprint?” Nevertheless, a small community of mostly young and passionate collectors began to make it a fascinating new field of collecting. It also provided a financially lower entry level for collectors who couldn’t afford original artworks. The system of signed and numbered editions which had already proven to work in the world of prints (lithographs, etchings, and serigraphs) gradually began to be adopted by photographers. With it, trust developed and photography grew as a market.

German photo artist Andreas Gursky poses in the front of the photographic work Lager (2014) in the exhibition “Andreas Gursky” at the Museum of Fine Arts Leipzig, in Leipzig eastern Germany on March 24, 2021. Photo by Jens Schlueter/AFP via Getty Images.

There was initially very little overlap between collectors of photography and collectors of contemporary art. Size had something to do with it. Before digital photography, there was a limitation in what size a negative could be printed. Towards the end of the 1980s, things began to change. I remember the excitement of walking into the Ileana Sonnabend Gallery in New York and seeing the exhibition of Peter Fischli and David Weiss. It was a series of ultra large color photographs beautifully produced and mounted of postcard motifs such as the Eiffel Tower, the Matterhorn or the Taj Mahal.

In 1992 I experienced similar excitement when I visited an Andreas Gursky exhibition at the Kunsthalle Zurich. The actual scale of the works besides their obvious quality and originality was highly seductive. By that time contemporary art collectors were being lured in, and very rapidly there was more and more overlap between the markets for contemporary art and photography. So much so that from 2002 onwards, contemporary sales at Sothebys, Christie’s and Phillips de Pury (which then made photography one of its main pillars besides cutting-edge contemporary art and design) included an ever-growing proportion of photography or photography-based art. There were occasional fights between the contemporary art and photography specialists inside the main auction houses about which auctions some photography-based works should be included in.

The taking of photographs itself evolved quite rapidly. A milestone was the introduction of the Polaroid SX-70 camera in 1972. It was a beautiful looking foldable object which made a very satisfying noise when you pressed the shutter. Top photographers such as Helmut Newton began to use Polaroids for visualizing the initial compositions of their shots, like a painter would have made preparatory sketches. As a young specialist at Sotheby’s I was given one. It allowed me to take multiple photographs on visits to clients, which I could then discuss with my more senior colleagues when back at headquarters. The Polaroids made by Andy Warhol are a treasure trove and contrary to what was expected back then, Polaroid photographs have aged quite well and have made it up to now without serious physical deterioration.

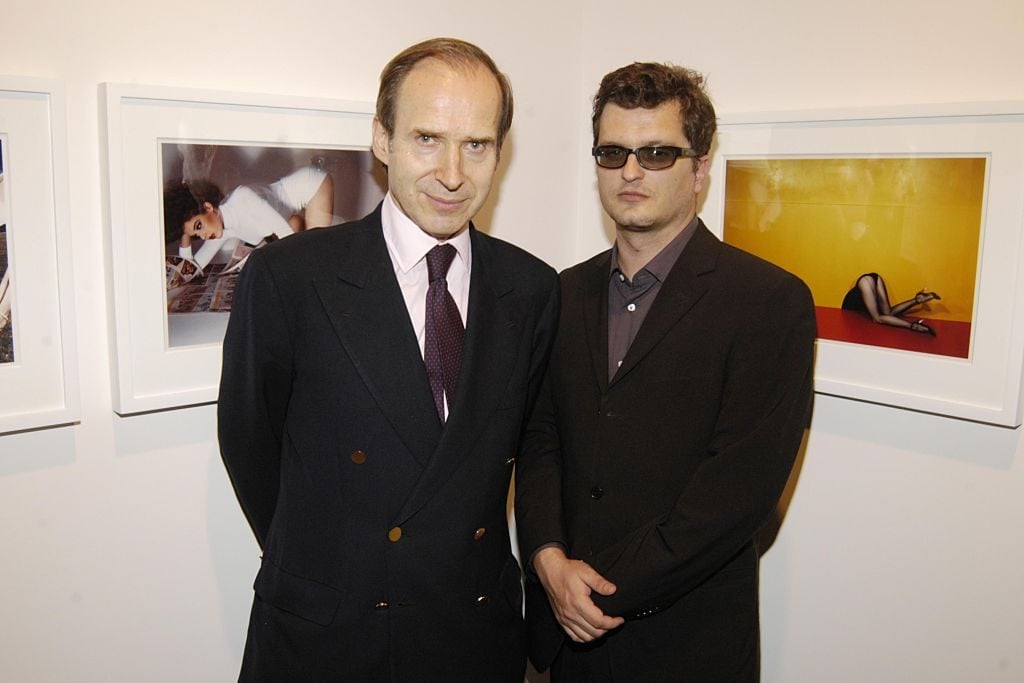

Simon de Pury and Samuel Bourdin attend Phillips de Pury and Company private reception of “Guy Bourdin: A Message for You” on November 26, 2008 in New York City. Photo by Scott Rudd/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images.

The advent of digital photography and the access to digital cameras from the late 1990s onwards made taking photographs much easier. Since being a child, I loved taking photographs but I hated carrying a camera around. It made you look like a tourist and they were too complicated to use. The introduction of the pocket sized cameras such as the Canon IXUS in 2000 changed everything. You could take it everywhere and snapping away was idiot proof. It still meant, however, carrying your early Blackberry and your pocket camera. The arrival of the iPhone was the final breakthrough. You had it all packed into one single gadget.

Initially the pixelization of the images taken with the phone was too low, but with recent models it has improved dramatically. Suddenly, every single human became not just a photographer, but also an editor, an artist, a cinematographer, a writer, a commentator, an influencer, a follower, as well as a full-blown narcissist. The billions of photographs that are being uploaded onto Instagram and other social media platforms on a daily basis make us all great consumers of photography and voyeurs. In order to stay abreast of the competition such as Snapchat and TikTok, Instagram introduced Stories, Reels and Live where the moving image is in the process of overtaking the still image. One could have expected the explosion of photography caused by the technological revolution to have a very beneficial effect on the market for photography. This has not really been the case. For the time being there has been a slight softening in the demand for the work by the photographers who made their mark in the 90s and early 2000s.

Video and film began to be quite widely used by contemporary artists from the 1960s onwards. It remained, however, a mostly institutional market with some notable exceptions such as the private collection of Richard and Pamela Kramlich which is housed in their Herzog & de Meuron building in Napa Valley. Back in the days when I owned Phillips, I wanted to stage the first ever auction entirely devoted to video art. Luckily my colleagues managed to dissuade me, as it would have been a total and unmitigated commercial flop. The arrival of NFTs and blockchain is in the process of changing all that. In the same way that limited numbered editions eventually changed the market for photography, unicity or numbered editions will make art based on the moving image eminently more collectible.

General views of the exhibition by David Lachapelle “Atti Divini” (Divine Acts) at Reggia di Venaria Reale on June 13, 2019 in Turin, Italy. Photo by Roberto Serra – Iguana Press/Getty Images.

While artists today have infinitely more ways, possibilities, and media in which to express themselves, techniques that have been around forever, such as painting on canvas, sculpture in bronze, stone or wood as well as ceramics are flourishing. Works made in these time-tested techniques dominate the art market in monetary terms. Having visited with my two daughters the incredible interactive teamLab installations in Tokyo, having been mesmerized by the dazzling moving artworks of Turkish genius Refik Anadol, I cannot escape from the fascination for moving image artworks. I try to analyze why I nevertheless still prefer to collect art that doesn’t move or that you don’t have to switch on. Why do I still prefer to look at the Instagram grid of still images instead of all the moving alternatives? Could the reason be that it creates the illusion of suspension in time and therefore of timelessness? The constant movement of life around us permanently reminds us of the inexorable passing of time, and of the final destination of our terrestrial journey.

With age my attention span is getting shorter than it ever was. I rarely look at the full duration of a video art piece. I feel it steals time from me, whereas if I am standing in front of a still artwork it is me deciding whether I want to look at it for a split second or half an hour. Contemplating a great painting or photograph makes you forget the passing of time. Looking at a great photograph by Helmut Newton, Guy Bourdin, Anton Corbijn (whose work I currently have the privilege of presenting in a virtual exhibition), Mario Testino, David LaChapelle or Jürgen Teller will always fascinate me, and from a market perspective there are great days ahead for the collecting of photography as well, of course, of contemporary art and design.

Simon de Pury is the former chairman and chief auctioneer of Phillips de Pury & Company, former Europe chairman and chief auctioneer of Sotheby’s, and former curator of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection. He is now an auctioneer, curator, private dealer, art advisor, photographer and DJ. Instagram: @simondepury