Archaeology & History

Startling New Evidence Suggests Stonehenge’s Inner Stone Circle Was Originally Erected 175 Miles Away, in Wales

Archaeologists suspect Stonehenge's inner circle originally stood at Waun Mawn in Wales.

Archaeologists suspect Stonehenge's inner circle originally stood at Waun Mawn in Wales.

Sarah Cascone

Lending credence to an ancient legend, newly uncovered evidence suggests that Stonehenge’s inner circle of stones was originally erected in Wales, before being transported 175 miles and rebuilt on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England.

Archaeologists working on the Stones of Stonehenge project have found buried holes that once were part of a ring of stones that closely matches the dimensions at Stonehenge—and is located just three miles from a Wales mountain range that is home to the quarries where Stonehenge’s “bluestones” were originally mined.

“I’ve been researching Stonehenge for 20 years now and this really is the most exciting thing we’ve ever found,” Mike Parker Pearson, a professor of British later prehistory at University College London and the Stones of Stonehenge leader, told the Guardian. The team’s findings will be broadcast in a BBC documentary, Stonehenge: The Lost Circle Revealed, on Friday evening.

In the 12th century, Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote of how Merlin and his men stole the Giant’s Dance, a magical stone circle in Ireland, and rebuilt it in England as a memorial to the dead. The tale was long dismissed as a myth, but the new findings from Parker Pearson’s team suggests it may have been based in truth—especially because southwest Wales was considered Irish territory at the time.

This standing stone at Waun Mawn in Wales is now believed to be among the remnants of an ancient stone circle that was deconstructed and used in the building of Stonehenge. Photo by Paul R. Davis, courtesy of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales.

The site of a onetime stone circle near the Preseli Hills also conforms to a theory espoused by geologist Herbert Thomas in the Antiquaries Journal way back in 1923. He believed that Stonehenge’s bluestones, which weigh up to three tons, were originally part of a “venerated stone circle” in Wales.

“It seems that Stonehenge stage one was built—partly or wholly—by Neolithic migrants from Wales, who brought their monument or monuments as a physical manifestation of their ancestral identities to be re-created in similar form on Salisbury Plain,” wrote Parker Pearson in the journal Antiquity.

The Stones of Stonehenge team first began looking at the site of Waun Mawn, which is home to four prehistoric monoliths, back in 2010. They held off further investigations after initial scans with remote-sensing technology did not uncover signs of former stone holes. But when they returned for excavations in 2017, archaeologists were surprised to find holes where stones had been removed in ancient times.

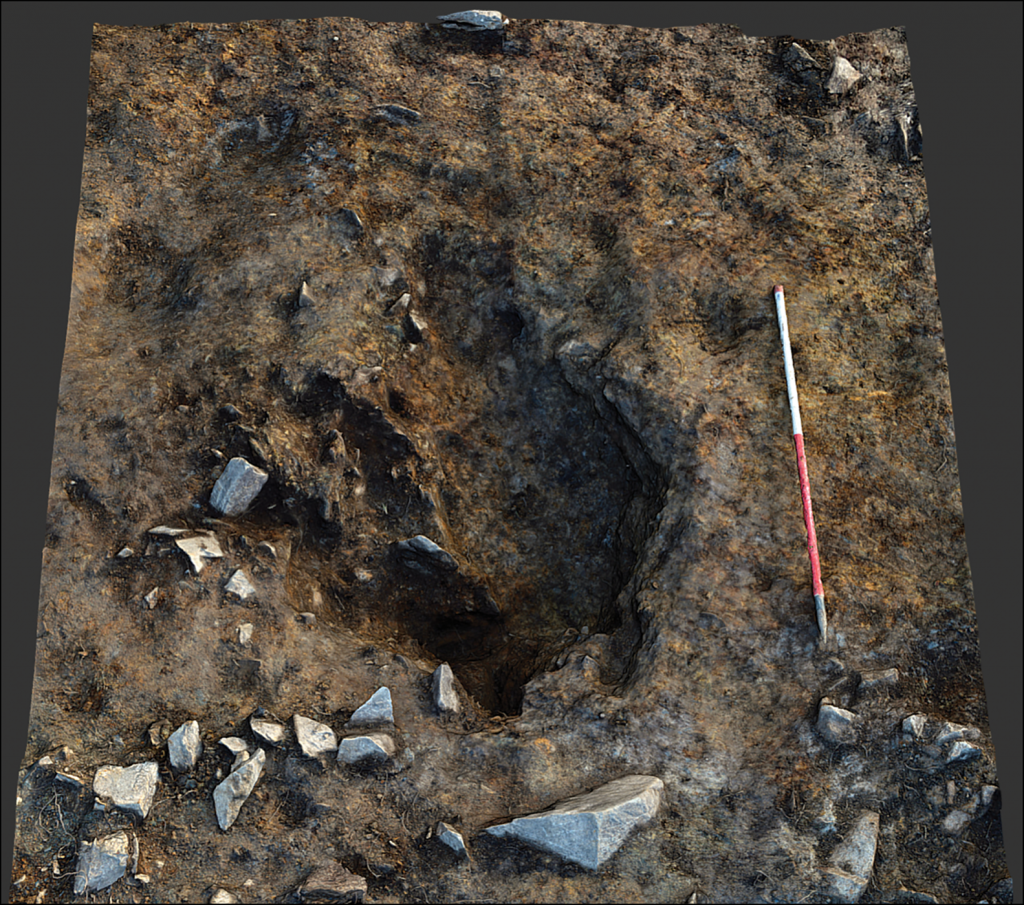

The remains of the stone circle at Waun Mawn in Wales during excavations. Photo by A. Stanford.

Now, it would seem that the four surviving stones and the six newly discovered stone holes were once part of a ring of some 30 to 50 stones. Like Stonehenge, the circle would have aligned with the midsummer solstice. Most convincingly, the imprint of one of the stone holes matches the shape of one Stonehenge’s bluestones almost exactly.

Waun Mawn is located just a stone’s throw (ahem) from the quarries that the Stones of Stonehenge project identified as the source of Stonehenge’s bluestone two years ago. But when Parker Pearson’s team carbon dated hazelnut shells believed to have been left behind by prehistoric miners after a snack, they were found to predate the monument’s erection in England, around 3,000 BC, by almost four centuries, suggesting a delay in Stonehenge’s construction.

That’s when Parker Pearson began to suspect that Stonehenge might be what he dubbed “a secondhand monument.” Now, he believes Waun Mawn might be “amongst the earliest stone circles in Britain,” and that it may be part of “several stone circles [that] were dismantled in the Preseli area to provide Stonehenge” with its bluestones.

A stone hole at Waun Mawn in Wales during excavations. The imprint of this stone (in the right half of the stonehole) reveals that the base of this stone had a pentagonal cross-section that matches a bluestone at Stonehenge. Photo by A. Stanford.

It’s a compelling theory, but it remains, of course, unproven. The findings at Waun Mawn “add to growing evidence for cultural links between the Preselis and Stonehenge that fills out the geological case for the region being the source of some of the Stonehenge megaliths,” Mike Pitts, a historian who has excavated at Stonehenge, told the Art Newspaper, but “there are too many unknowns” to know for certain.

Stonehenge’s larger standing stone monoliths, it now seems, are more locally sourced. Last year, after testing a core sample taken during repair work in 1958 and recently returned by a Florida retiree, archaeologists determined that the sarsens, as they are called, came from the West Woods area of Marlborough Downs—just 15 miles from Salisbury Plain.

How the ancients transported either set of stones, however, remains a mystery. But to make such an arduous task worth the effort, the bluestones “must have been considered as not just valuables” to the monument builders, Parker Pearson told National Geographic, “but the very essence of who they were.”