Art World

Where Did Stonehenge Get Its Stones? Scientists Have Solved the Age-Old Mystery—Thanks to a 90-Year-Old Retiree

The massive sarsen slabs came from an overlooked wood just 15 miles away.

The massive sarsen slabs came from an overlooked wood just 15 miles away.

Sarah Cascone

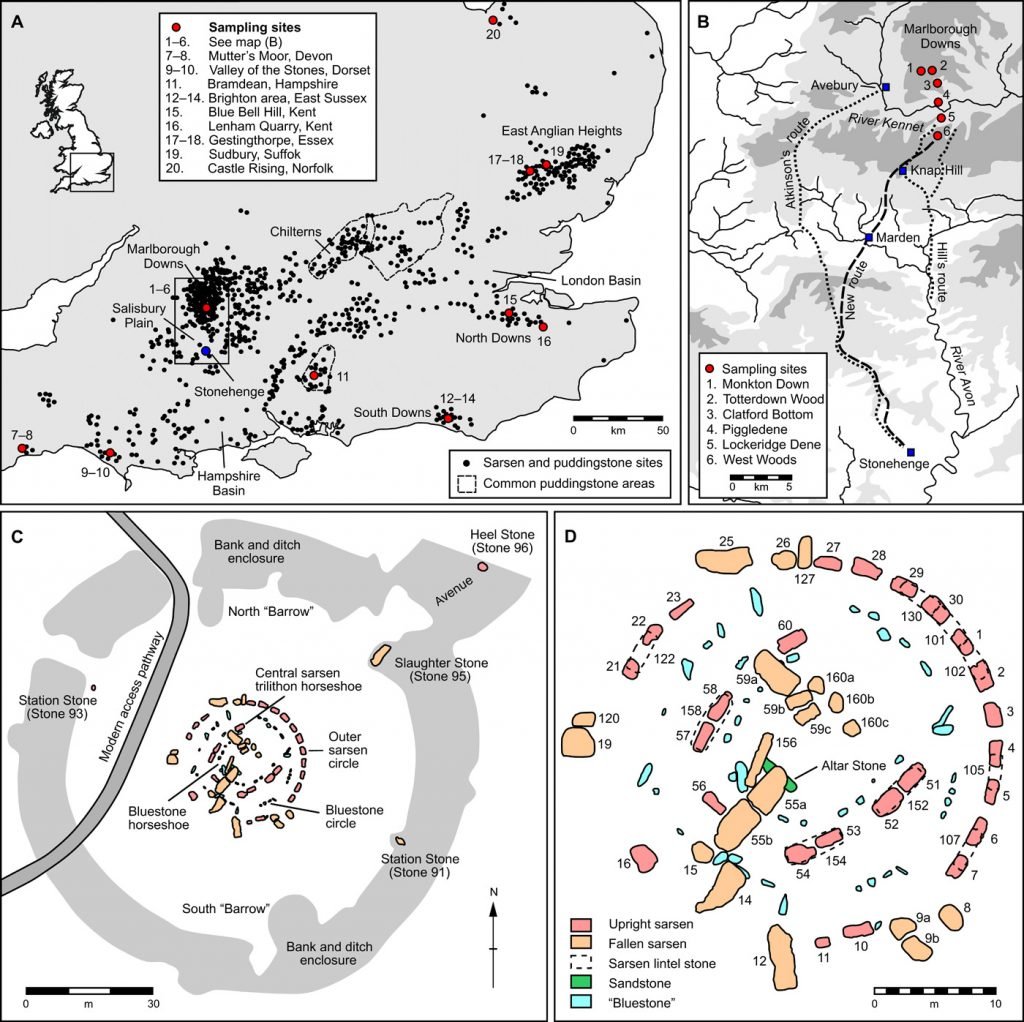

The origins of Stonehenge’s massive stone monoliths, long shrouded in mystery, have at last been demystified. Experts have traced them to boulders in the nearby chalk hills of Marlborough Downs, just 15 miles north of the prehistoric monument in Wiltshire, England.

The discovery, published this week by researchers from the University of Brighton in the journal Science Advances, actually confirms long-held theories that the sandstone slabs, called sarsens, were from somewhere in Marlborough Downs, but uses scientific testing to pinpoint the exact location to the West Woods for the first time.

“Until recently, we did not know it was possible to provenance a stone like sarsen,” David Nash, a geomorphologist and the lead author of the study, in a statement. “It has been really exciting to use 21st century science to understand the Neolithic past and answer a question that archaeologists have been debating for centuries.”

Nash believes the ancient builders transported the stones, which weigh up to 30 tons, down the Wiltshire Avon Valley to the east or via a western route across Salisbury Plain. “We can feel the pain of the Neolithic people who took part in this collective effort and think about how they managed such a Herculean task,” wrote Nash and his coauthor, Timothy Darvill, a Bournemouth University archaeology professor, in the Conversation.

A sarsen, like the ones at Stonehenge, in the West Woods, now known to be the origin of the prehistoric monument’s massive stone slabs. Photo by Katy Whitaker, courtesy of Historic England/the University of Reading.

Stonehenge actually contains two different kinds of stones, erected thousands of years apart. The sarsens are the larger silica stones in Stonehenge’s outer ring and center, each about 13 feet high and seven feet wide. There 52 on the site today, but experts believe that there were originally 80.

The other smaller stones within the inner circle are known as bluestones, erected around 3,000 BC. In 2015, experts found evidence that those stones came from the Preseli Hills, 180 miles away in western Wales. The exact sites, Carn Goedog and Craig Rhos-y-felin, were identified in 2019, after eight years of research. But investigations into the sarcens, erected around 2,500 BC, had lagged.

This stone core, drilled during repairs in 1958, has helped unlock one of Stonehenge’s undying mysteries. Photo courtesy of English Heritage.

The new research was made possible thanks to a former diamond cutter, Robert Phillips, who was involved in repairs carried out on the prehistoric structure in 1958. To re-erect a fallen trilithon, one of the three-piece standing stones, Phillips and his team drilled holes and inserted metal bolts to reinforce the cracked lintel stone.

Phillips kept one of the three-and-a-half foot cylindrical cores, which was set to be discarded, as a souvenir, hanging it in his office. Over sixty years later in 2019, Phillips, on the eve of his 90th birthday, returned the core to English Heritage, which oversees Stonehenge. (Half of one was rediscovered last year at the Salisbury Museum, but the whereabout of the remaining one and a half cores are unknown.)

In 1958, workers raised a standing stone at Stonehenge that had fallen down a century behind. Now, a core sample drilled during the repair work has helped identify the mysterious monument’s origins. Photo courtesy of English Heritage.

Immediately, archaeologists realized that this was a rare opportunity to investigate the landmark’s origins—drilling the stones at Stonehenge today is prohibited. “It’s the sarsens’ time, really,” Robert Ixer, a geologist at the University College London Institute of Archaeology, told Science magazine. “They have been for too long neglected.”

Unlike the stones on site, the core doesn’t have any surface weathering, which can affect readings of its chemical composition. More importantly, the team was allowed to use destructive sampling, pulverizing about half the sample for a thorough analysis creating a “geochemical fingerprint.” Then, they used a portable x-ray spectrometer to take non-invasive surface readings of all 52 stones on site.

Jake Ciborowski using a portable x-ray fluorescence spectrometer. to conduct surface readings on one of the 52 sarsen stones at Stonehenge. Photo by David Nash.

All but two shared a near-identical chemical makeup with the core sample, suggesting a common origin. The stones are 99 percent silica, with traces of aluminum, carbon, iron, potassium, and magnesium.

Comparing the chemical signature to mass spectroscopy readings on samples from 20 boulder fields across southern and eastern England, the researchers identified the West Woods as a match with nearly 100 percent certainty.

“We weren’t really setting out to find the source of Stonehenge,” Nash told the Irish Times. “We picked 20 areas and our goal was to try to eliminate them, to find ones that didn’t match. We didn’t think we’d get a direct match. It was a real ‘Oh my goodness’ moment.”

University of Brighton geomorphologist David Nash examines a core sample removed from Stonehenge during repairs in the 1950s. Photo by Sam Frost, courtesy of English Heritage.

The discovery narrows the point of origin from the 75-square-mile Marlborough Downs to just two square miles in the West Woods, but leaves the question of how the builders chose where to get the stones.

“When sourcing the sarsens, the over-riding objective was size—they wanted the biggest, most substantial stones they could find and it made sense to get them from as nearby as possible,” said English Heritage historian Susan Greaney, in a statement. “This is in stark contrast to the source of the bluestones, where something quite different—a sacred connection to these mountains perhaps—was at play.”

Despite centuries of speculation about, only two people are known to have hypothesized that ancient builders sourced the Stonehenge sansens in the West Woods. In 2017, a former Stonehenge tour guide and amateur archaeologist published a blog post on the history of sarsen extraction pits in the West Woods, suggesting it as a possible origin of Stonehenge’s monoliths.

Diagrams of Stonehenge and the surrounding area. Courtesy of the University of Brighton.

The other was John Aubrey, biographer and philosopher who surveyed Stonehenge in the 17th century. He suggested the stones came from a quarry pit 14 miles away in what was then “Overton Wood”—likely the West Woods.

“The West Wood was overlooked because it’s under ancient woodland, and a lot of sarsens were removed in the 19th century for roadstones… but there are still sarsens buried in amongst the trees,” Greaney told the Telegraph.

Even with this long-awaited find, however, Stonehenge still holds plenty of secrets. Experts have yet to determine, for example, exactly how the builders chose where to get the stones. Plus, “we still don’t know where two of the 52 remaining sarsens at the monument came from,” Nash told NBC News. “There remain mysteries to solve.”