Law & Politics

‘Can Everyone Agree This Is a Beautiful Painting?’: A Divided U.S. Supreme Court Reviews a Rare Art Case Over a Nazi-Looted Pissarro

David Boies, a leading civil litigator, argued for the painting's return.

David Boies, a leading civil litigator, argued for the painting's return.

Sarah Cascone

The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments on Tuesday about the disputed ownership of a painting by Camille Pissarro that Lilly Cassirer Neubauer, a Jewish woman fleeing Nazi Germany, sold in 1939. The canvas has belonged to Spain since 1993, where it is part of the collection of Madrid’s Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, a state-run museum.

The issue before the court in Cassirer, v. Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, however, did not delve into the specifics of the painting’s sale and the merits of claims that it was looted by the Nazis. In fact, both parties agree that it was.

Instead, lawyers representing the museum and David Cassirer, the great-grandson of Cassirer Neubauer, limited their argument to the issue of “choice of law.” That’s the question in litigation that determines which country or state’s laws should be applied in the case. The court’s decision will determine whether the litgation will proceed at all.

Listening to the audio livestream of the arguments, heavily steeped in legalese, it was easy to forget that there was even a painting involved—until near the end of the proceedings, when Justice Stephen Breyer stepped in to ask, “Can everyone agree that this is a beautiful painting?”

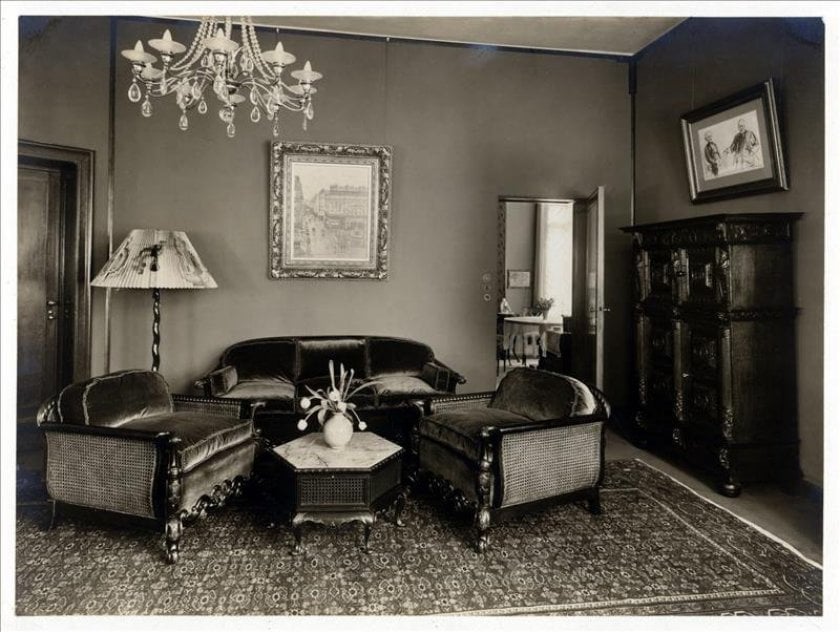

The Camille Pissarro painting hanging in the Berlin apartment of Lilly Cassirer (ca. 1930). Photo courtesy of David Cassirer.

Titled Rue Saint-Honoré, dans l’après-midi. Effet de pluie (1897), the Impressionist canvas seemingly disappeared after Cassirer Neubauer sold it in exchange for just $360—a sum she never received—and visas for her and her husband to leave the country. After the war, she sought its return and, after 10 years, won a $13,000 settlement from the German government through the U.S. Court of Restitution Appeals.

The artwork eventually resurfaced in the U.S., where Swiss collector Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza bought it in 1976. It was one of 775 artworks he sold to Spain in the $338-million deal that eventually birthed the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza.

That’s where Claude Cassirer, Cassirer Neubauer’s grandson, spotted it in 2001. He called for its return, but by that point it had already been on view at the museum for eight years—and under Spanish law, public possession of someone else’s property for six years is enough to transfer good title, even if it was originally stolen.

That isn’t the case in California. Under that state’s law, once an object has been stolen, clean title can never pass to subsequent owners, even if they purchased it in good faith. So the question facing the court is which of those two rules apply. U.S. law does not normally allow suits against foreign countries, except, as laid out in the 1976 Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, in cases where property was stolen “in violation of international law.” (This exception has allowed Jews persecuted by the Nazis to pursue restitution of their personal belongings.)

David Boies, the lawyer for David Cassirer—arguing remotely due to a positive COVID-19 diagnosis, according to Law.com—maintained that the law requires that a foreign state receive the same treatment as a private individual under the same circumstances. That would mean adjudicating under state law, not federal common law.

Thaddeus J. Stauber, representing the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation, countered that California’s connection to the case was tenuous. Claude Cassirer only filed the suit there, Stauber said, because that’s where he was living at the time. (It wasn’t mentioned in the hearing, but the painting had been illegally exported to California back in 1951.)

Stauber also maintained that foreign states should be tried under federal common law, not individual state laws, otherwise countries would be subject to different legal standards depending on the state in which the lawsuit was filed.

“Welcome to the United States—that’s how the courts work,” Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. responded.

“If California law and federal law, you say, both correctly point to the application of Spanish law, what are you afraid of?” Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked Stauber. “You’re afraid of something. You’re afraid that they’re right, that some aspect of California law can hurt you, correct?”

Stauber denied it.

Two lower courts have previously ruled in favor of Spain, on the basis that Spanish law applied in the case. The museum has refused to consider restitution, even after a judge pointed out that keeping it contradicted “Spain’s acceptance of the Washington Conference Principles,” a non-binding international agreement to return property seized by the Nazis.

Should the Supreme Court find that the case should be heard under California law, the case will return to the lower court to be readjudicated. If the court upholds the earlier ruling of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, the painting will stay in Spain. A verdict is expected in July.