Law & Politics

The U.S. Supreme Court Will Offer the Final Word in a Two-Decade Battle Over a Nazi-Looted Pissarro Painting

No one denies that the artwork was stolen, but two lower courts have ruled against restitution of the painting.

No one denies that the artwork was stolen, but two lower courts have ruled against restitution of the painting.

Sarah Cascone

A two-decade-long legal battle over a painting by Camille Pissarro will be heard in the U.S. Supreme Court on January 18.

The work at the center of the dispute, titled Rue St Honoré, apres-midi, effet de pluie (1897), was sold by Lilly Cassirer Neubauer, a Jewish woman living in Berlin, for $360 to get visas to flee Nazi Germany. She never received the money.

The painting eventually made its way to the U.S., and in 1976, the Swiss collector Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza bought it at a New York gallery for $275,000. He sold his 775-piece art collection to the Kingdom of Spain for $338 million in 1993, which opened the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in his honor. The Pissarro remains on view there today, and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation has been steadfast its rejection of calls for restitution.

“We are pleased that the U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to review this miscarriage of justice,” the claimant’s lawyer, Stephen Zack of Boies Schiller Flexner, told the Art Newspaper, which first reported the news. “State and federal laws and policies, as well as international agreements to which the U.S. and Spain are parties, make it clear that looted artworks should be restored to their rightful owners.”

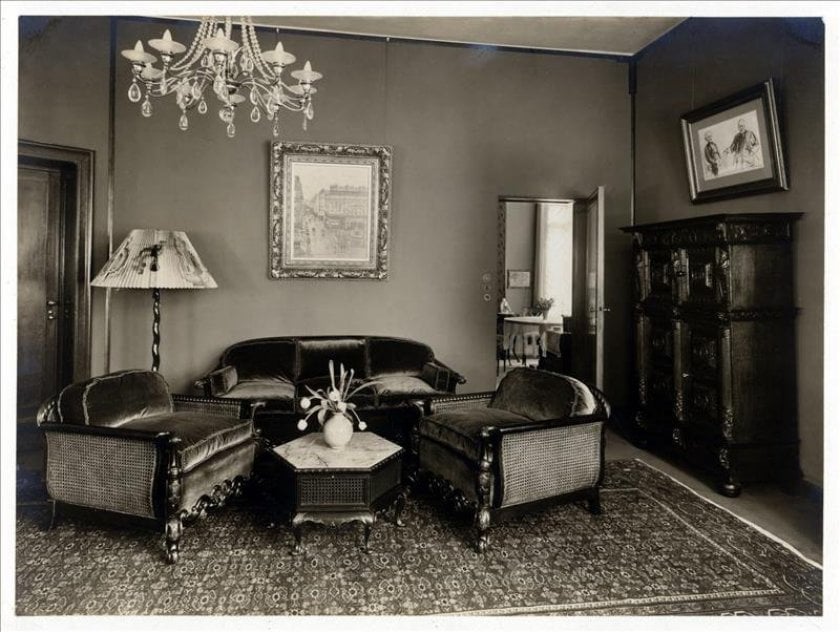

The Camille Pissarro painting hanging in the Berlin apartment of Lilly Cassirer (ca. 1930). Photo courtesy of David Cassirer.

After the war, Cassirer Neubauer unsuccessfully looked for the painting, accepting a $13,000 settlement from the German government following a nearly decade’s long proceeding at the U.S. Court of Restitution Appeals. Cassirer Neubauer, who died in 1962, never waived her right to the painting should it be found.

Her grandson, Claude Cassirer, discovered the lost painting’s whereabouts and in 2001 began to press for its return, filing a lawsuit against the foundation in 2005. Since his death in 2010, his son David Cassirer has continued the battle.

The case is complicated by the fact that the foundation is an instrumentality of the Kingdom of Spain, and foreign countries normally cannot be sued under U.S. law. But Cassirer Neubauers’s forced sale of the painting falls under the 1976 Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act’s “expropriation exception,” covering property taken “in violation of international law.”

In 2015, the United States District Court for the Central District of California ruled in favor of Spain, finding that Spanish law, not U.S. law applied in the case. The judge suggested that the museum should reconsider its position “in light of Spain’s acceptance of the Washington Conference Principles,” but said the court was unable to compel it to do so. An appeals court upheld that ruling in 2020.

“The reason the painting should be returned is because the defendants know how it was obtained by the Nazis and that it is rightfully owned by the Cassirers,” Zack told Artnet News in an email. “It is clear that the defendants knew or should have known that the painting was stolen by the Nazis from the Cassirers and could not have obtained good title in that situation.”

Representatives for the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation did not respond to a request for comment by press time.

The issue will likely come down both to jurisdiction and the particulars of property law. In Spain, if you possess someone else’s property in a public manner for six years, you acquire good title. The museum had displayed the Pissarro for nearly eight years before Cassirer called for its return.

Under California law, because the Nazis initially stole the work, a clean title can never pass to subsequent owners, even if they purchased it in good faith.

If the Supreme Court finds that California law supersedes Spanish law, the Cassirers would likely prevail in their suit. The nation’s highest court will decide the extent of foreign nations’ liabilities in U.S. courts, and whether the lower appeals court used faulty reasoning when it chose what law to apply to the claim.