Art World

Considering the Overlooked History of ‘Black Romantic’ Painting + 4 Other Great Art Essays Worth Reading From This January

A round up of ideas from around the art web.

A round up of ideas from around the art web.

Ben Davis

It’s near impossible to keep up with everything that comes rocketing at you through the newsfeed each day—let alone everything that was published about art in the last four weeks. So here’s my attempt, at the end of the month, to crack open the virtual magazine rack, read a bunch, and sift for ideas I think are worth debating or holding on to. If there’s something I missed that was good, I probably just ran out of time to read.

Here are five essays that I think are worth sharing with you from January 2021.

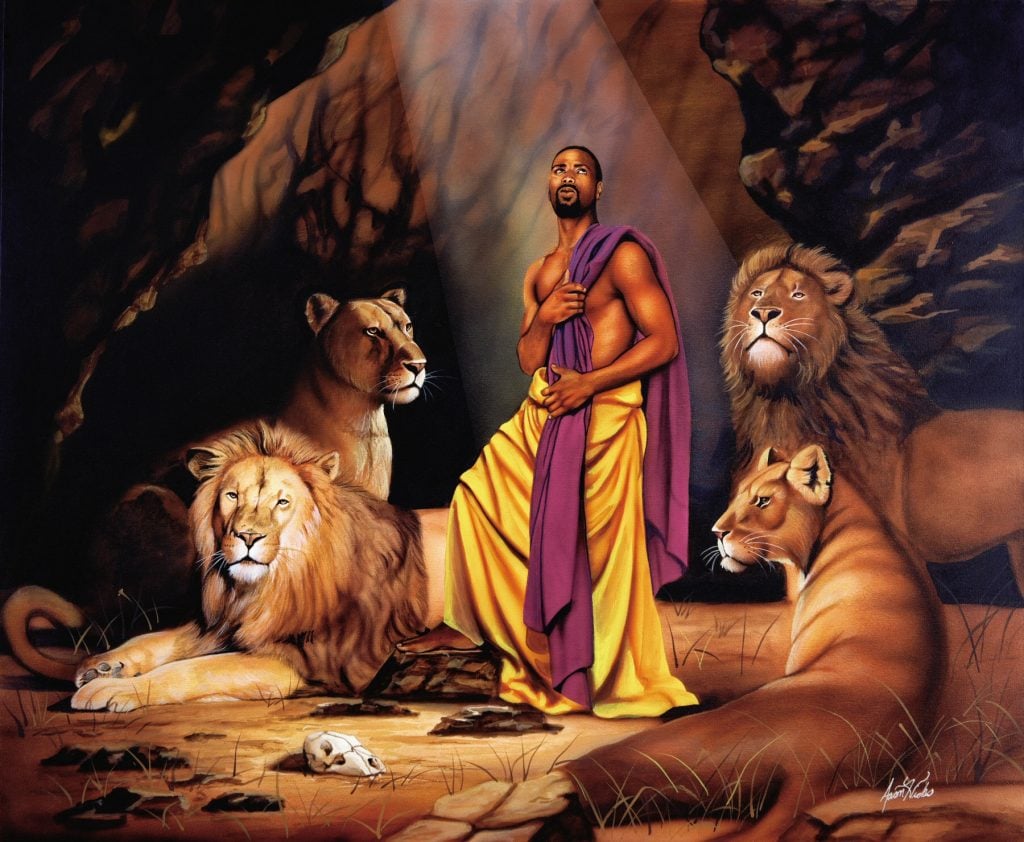

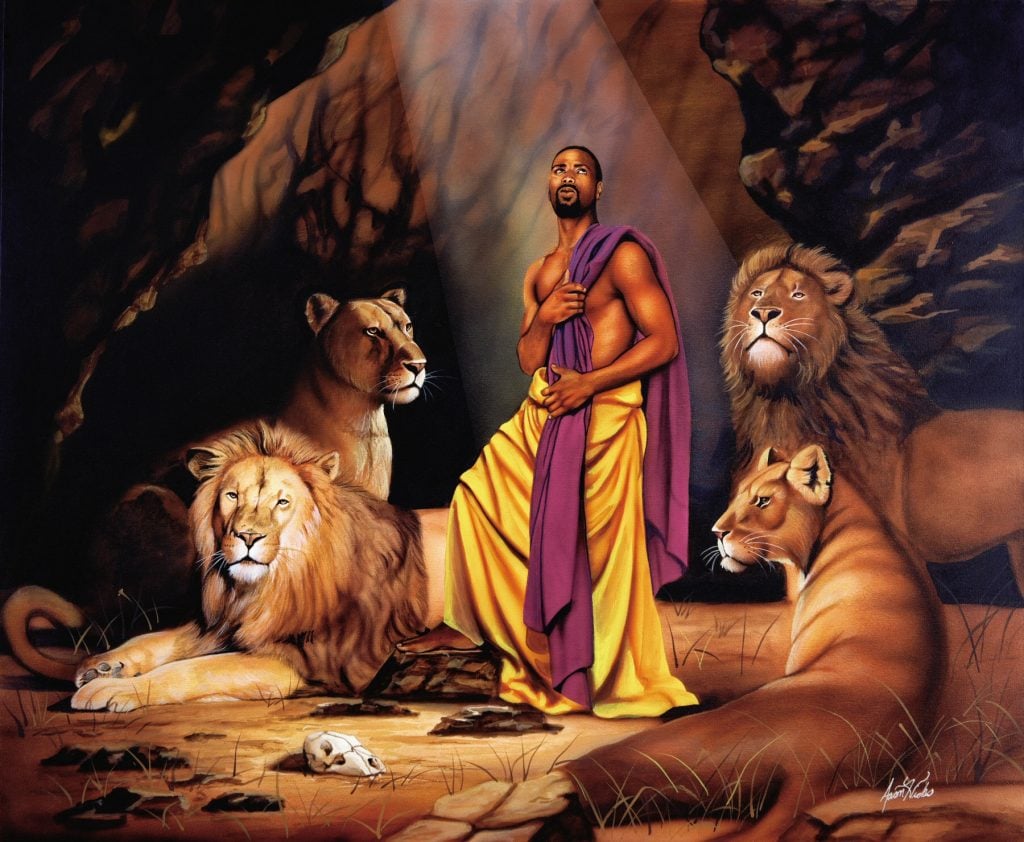

Just a great essay, walking through the history of what Sanders calls the “Black Romantic,” the current of under-documented but extremely popular painting rooted in Black church life and community uplift: “representational, mixed media, superlative in its sentimentalism and in an unambiguous race pride owed to a glamorized, monarchical African past.” Sanders takes the style seriously as a cultural force but also puts it into dialogue with the more critically exalted forms of Black experimental art that entered the conversation in the ‘90s.

With the pandemic still throwing people back into atomization and powerlessness, Levine’s wide-ranging, bracing personal account looks back at the lived experience of AIDS activism of the ‘80s and ‘90s as a model of taking a stand against a different kind of social isolation. She tracks how, in the face of mainstream silence about the AIDS epidemic, artists such as Ray Navarro and David Wojnarowicz helped forge the tradition of funeral-as-protest.

A look through the lens of Shannan Clark’s important-sounding new book, The Making of the American Creative Class, at the predicament of contemporary artists, from the point of view of a former art student and art handler. The “creative class” has sometimes been offered up as replacing or displacing the working class as its more glamorous heir. Kaiser-Schatzlein walks through how the existence of a robust art scene has always been defined by the much wider strata of art-adjacent industries and communities that serve as its hidden foundation.

Fischer, of the group Occupy Museums, surveys how recent efforts to politicize the art world have been displaced into a rhetoric of “anti-populism,” serving as a form of what he calls, following Olúfémi O. Táíwò, “elite capture,” whereby popular anger at injustice is reinterpreted in terms that redirect the conversation to issues faced by the populace’s best-off layers. Bonus: Fischer’s accompanying artworks channel recent headlines into the graphic language of Populist-era cartoons.

Reflections on the mutation of countercultural in the face of platform capitalism, and how the hyper-performativity of social media is sending those looking for meaning to find communion in what Busta terms the “dark forest,” the parts of the internet based on anonymity and self-consciously at odds with visibility.