Art & Exhibitions

Art Deco Star Tamara de Lempicka Has Never Been More Popular. Here’s Why

Furio Rinaldi, co-curator of the De Young's major retrospective, explains what has made Lempicka's art last.

A major retrospective of Art Deco darling Tamara de Lempicka has opened at the De Young Museum in San Francisco, ranging from some of her most celebrated paintings to lesser-known drawings that are only now getting their deserved attention.

Furio Rinaldi, who co-curated the show with Gioia Mori, said in an emailed interview that the exhibition has been “very popular,” even if many people from the audience “admittedly never heard Lempicka’s name before.”

“They respond passionately to her iconic Art Deco portraits and to the artist’s resilient life journey,” Rinaldi said. “Those from the audience who are more ‘in the know’ have expressed their particular appreciation in discovering the artist’s drawings—her draftsmanship is exquisite—and some lesser-known and rarely seen paintings, like her early Cubist still lifes.”

The show marks the first major retrospective of the artist’s work in the United States, more than four decades after her death. It unites over 120 paintings as well as other Art Deco sculptures and objects from the museum’s collection that help put her practice into historical context.

Tamara de Lempicka. Kizette on the Balcony (1927). Photo courtesy of Jacqueline Hyde/Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1898, Lempicka survived the Russian Revolution and relocated to Paris, where her bold, stylized portraits of society figures and her opulent lifestyle gained her fame and clientele amid the cultural elite of the 1920s and 1930s.

“In her time, Lempicka received critical praise at the Parisian salons and international exhibitions: as early as 1927 her works were acquired by museums, including the Musée d’art de Nantes and the future Pompidou,” Rinaldi said.

But the painter’s legacy was nearly lost to obscurity. Despite success in Paris, the Jewish artist was forced to flee at the outbreak of World War II and fell victim to changing art trends after the war. Her work was only rediscovered again in the 1970s, following a resurgence of interest in Art Deco. Even then, her legacy had to compete with those of famous male artists.

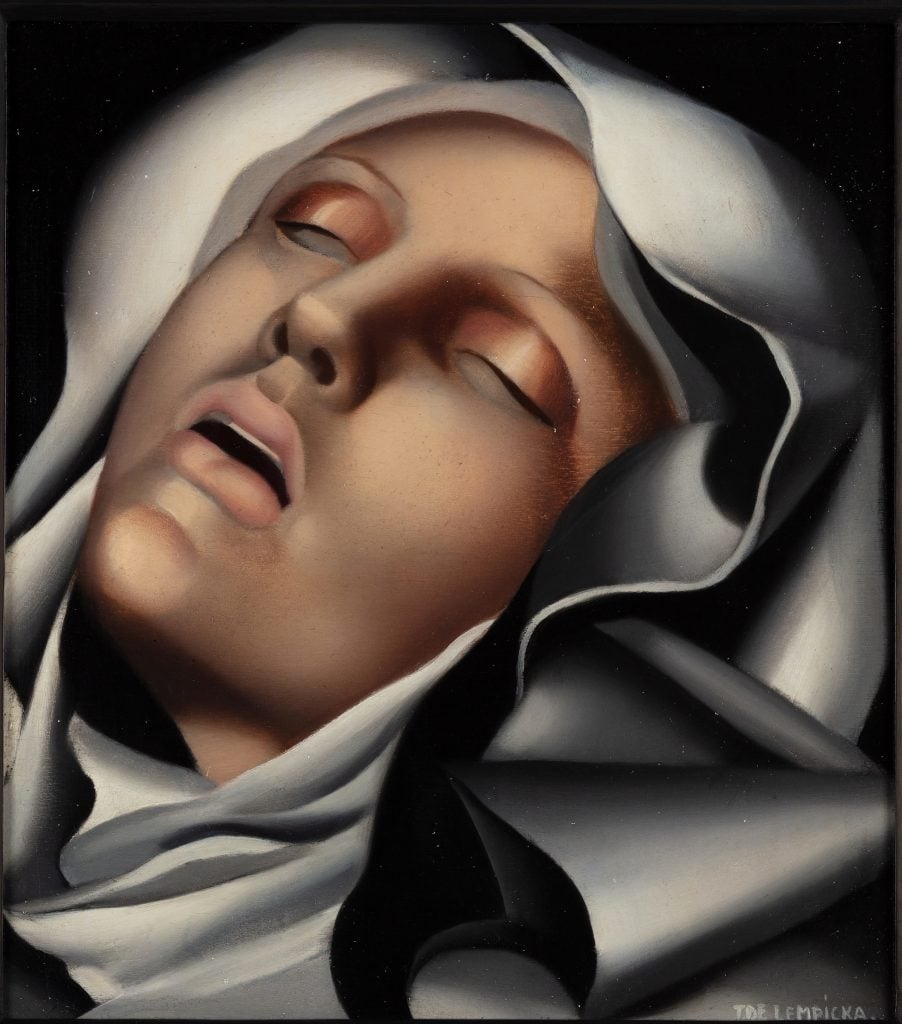

Tamara de Lempicka. The Communicant (1929). Photo courtesy Arnaud Loubry/Centre Pompidou/Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

In recent years, the creative world has made efforts to give Lempicka the limelight and capitalize on the glamor of her character, including a short-lived Broadway show starring Eden Espinosa as Lempicka. Sotheby’s also presented a selling exhibition of her work earlier this year.

“This exhibition aims to reassess her defining role within the development of Art Deco and, more broadly, to present her as a highly original artist who contributed to the international modernist movement—specifically to its classical declination in the ‘rappel a’ l’ordre,’ or ‘return to order,’” Rinaldi said.

Which of the works in the De Young exhibition were particularly pivotal in the artist’s career? Rinaldi pointed to Kizette at the Balcony (1927), La belle Rafaëla (1927), and Young Woman in Green (1931).

Tamara de Lempicka, Young Woman in Green (1927–30). Centre Pompidou, Paris, purchase, 1932, inv. JP557P. © 2023 Tamara de Lempicka Estate, LLC / ADAGP, Paris / ARS, NY.

In Kizette, the artist painted her daughter Marie-Christine in what Rinaldi called a “symphony of metallic grays.” It was among the first of her works that received widespread critical praise when it was shown at the Salon d’Automne of 1927. “It can be seen as an allegory of pubescence, as the young Kizette occupies, quite physically, a liminal space between the world of childhood and the modern metropolitan world of adulthood, seen behind the rails,” Rinaldi said.

As for the painting of Rafaela, a model who served as a muse for the artist for several of her most famous paintings, Rinaldi called it “quite phenomenal” for how she depicted the female nude with a feminine perspective rather than with a heterosexual male gaze.

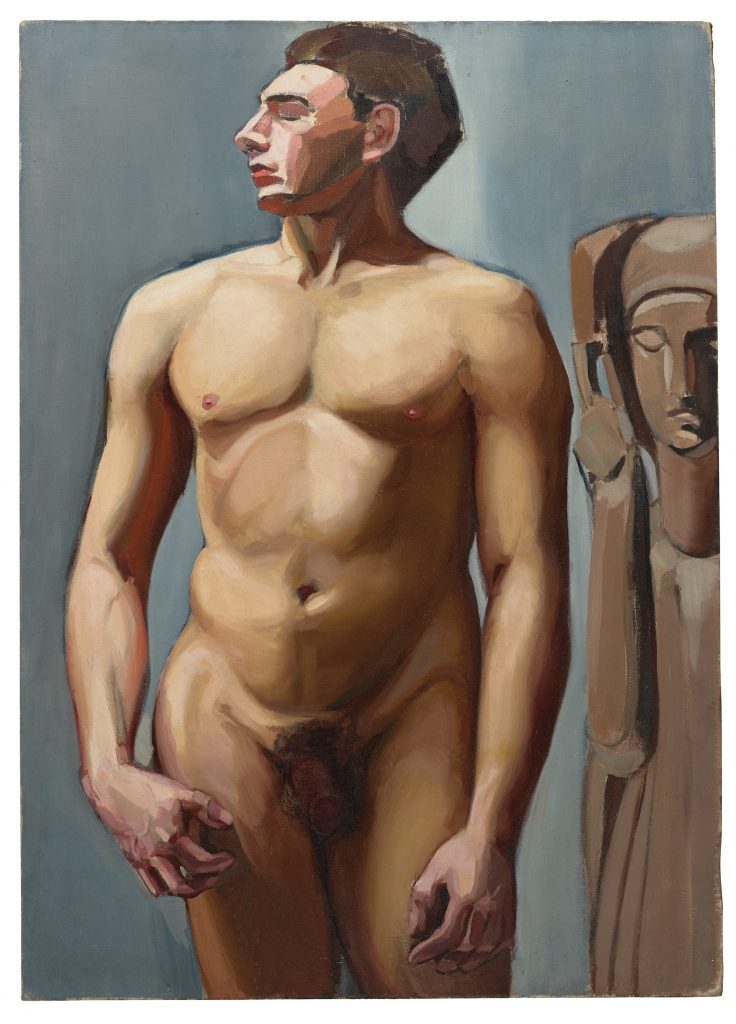

Tamara de Lempicka. Male Nude (ca. 1924). Photo courtesy of Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

“What she brings to this historical cannon is an entirely modern feminine perspective that celebrates womanhood and women’s sexuality,” Rinaldi argued. “The model in the painting is completely self-absorbed in her own pleasure.”

But the key Lempicka painting in the show is likely her work Young Woman In Green, which Rinaldi called an “emblematic image” of Art Deco. That work, he said, “encapsulates the optimism” and the “feminine freedom” of the interwar period.

Installation view showing a sculpture and paintings by Tamara de Lempicka at the de Young Museum. Photo courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Within this show’s attempt to show the complexity of her practice, a fourth work stands out to Rinaldi for providing special insight: Woman with a Green Glove (1928). An unfinished work, it highlights her layered design process.

The painting depicts an androgynous and unidentified woman with a boyish haircut who is wearing a “hyperfeminine” white dress that emphasizes her “powerful sensuality,” in Rinaldi’s words.

A photograph of the artist Tamara de Lempicka at the entrance to an exhibit of her work at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. Photo courtesy of Randy Dodson/Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

It was painted with a polished finish on a large wood panel, perhaps inspired by the artist’s knowledge of religious icons. It also has elements that reprise the 16th-century Italian Mannerist portraiture by the likes of Bronzino and Pontormo.

“In the research leading to the exhibition, I was particularly impressed to learn how the knowledge and appreciation of the Old Masters informed Lempicka’s figural vocabulary and infused her pictorial language with great sophistication,” Rinaldi said. “Her use of visual sources from the past is quite clever and extremely creative, for example in her adoption of details from a 16th-century Madonna by Parmigianino for her Sapphic painting Printemps (Spring).”

“Tamara de Lempicka” is currently on view at the de Young Museum, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive, San Francisco, through February 9, 2025.