Art & Exhibitions

A Major Show of Contemporary African Photography at Tate Modern Considers the Medium As a Tool for World-Building. Here Are 5 Exhibiting Artists You Need to Know

Osei Bonsu walks us through some of the show's most memorable images.

Osei Bonsu walks us through some of the show's most memorable images.

Sarah Cascone

During the colonial period, the camera became something of an imperial device, as Western images defined narratives about the history, culture, and identity of the African continent. Now, in its first major exhibition of contemporary African photography, the Tate Modern in London is showcasing the work of a new generation African artists using the medium on their own terms.

“A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography” features 36 artists—working in photography, video, and installation—who represent different generations and a wide span of geography. Each offers their own unique perspectives on Africa and its relationship with the wider world, informed by history while looking to the future with hope.

The exhibition is curated by the museum’s international art curator, Osei Bonsu, together with assistant curators Jess Baxter and Genevieve Barton and former assistant curator Katy Wan.

“It’s not a traditional photography survey. I don’t really think that Africa can be summarized or distilled into one large exhibition,” Bonsu told Artnet News. “This was more of an attempt to tell very specific stories about Africa through the lens of artists who were either living and working on the continent, or were paying homage to many of the traditions and visual practices that, in my opinion, best reflected the way that we see photography in Africa.”

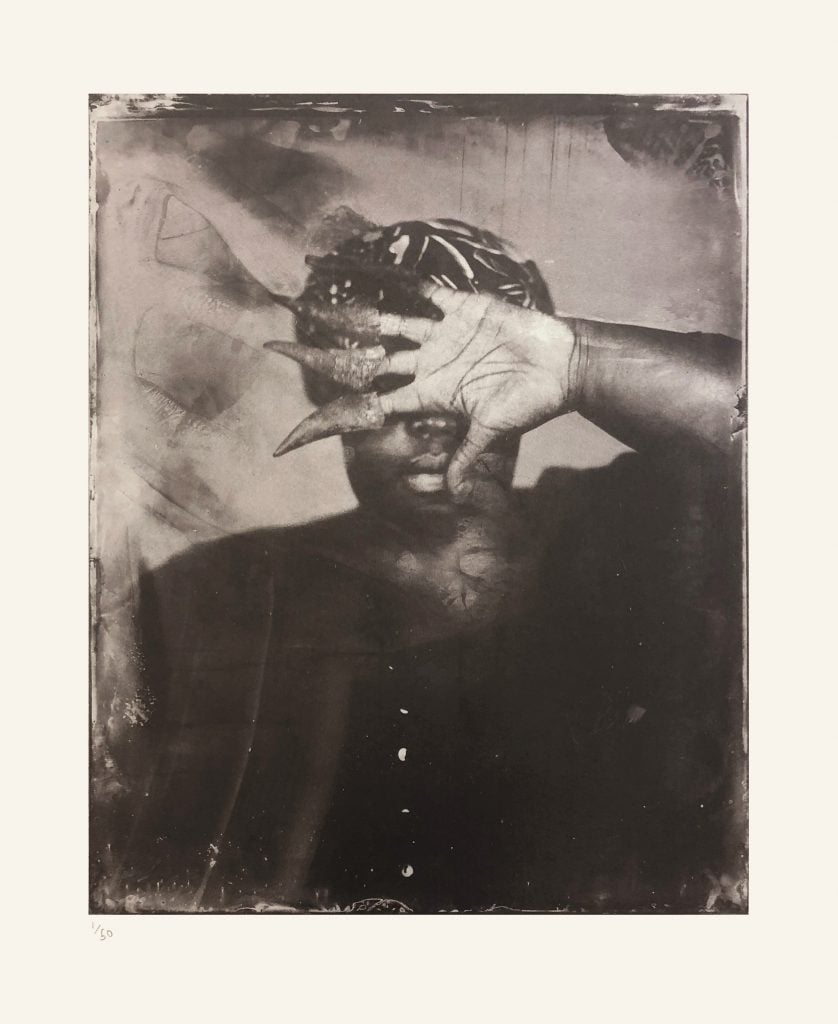

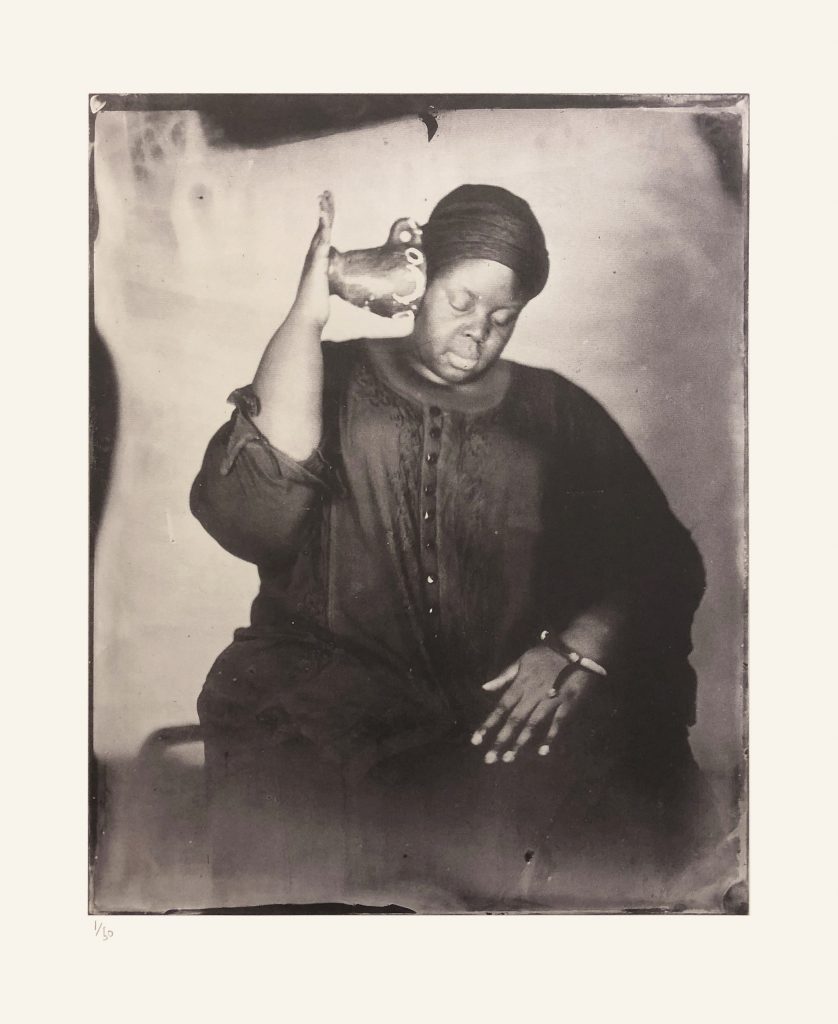

Khadija Saye, Ragal, “in this space we breathe” (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist.

The show features about 100 works presented in seven thematic sections by artists including Leonce Raphael Agbodjélou, Edson Chagas, Zohra Opoku, Kudzanai Chiurai, Wura-Natasha Ogunji, and Zina Saro-Wiwa.

Some photographs imagine alternate histories for the continent and its global diaspora, including the recreation of a royal precolonial past, with African kingdoms ruled by ancient dynasties.

Drawing on the more recent past, other photographers engage with traditions of studio photography, which became popular in African in the 1950s and ’60s as many nations achieved independence. These studios allowed African families to get their portraits taken, often for the first time—and the bonds of kinship captured in these images still resonate in their contemporary counterparts.

There are also photographs showing harsh truths about our present day reality and the growing climate emergency, documenting the rapid growth of Africa’s urban spaces—as well as hopeful imaginings of postcolonial utopias.

Together, the artists both reclaim African history and invite viewers to reconsider the continent’s place in the world, underscoring the importance of cultural memory and identity.

Ahead of this week’s opening, we spoke with Bonsu about the work of five of the artists in the show.

George Osodi, HRM Agbogidi Obi James Ikechukwu Anyasi ll, Obi of Idumuje Unor (in Palace) 2012, “Nigerian Monarchs.” Photo courtesy of the artist.

Osei Bonsu: “These images are about the role of traditional Nigerian monarchs in contemporary society. Before the amalgamation of Nigeria’s Northern and Southern Protectorates in 1914, these rulers would have been the kings and queens of various ethnic groups and communities. They no longer hold constitutional rights, but are the custodians of culture and kind of intermediaries for their community.

George is looking at the power and majesty and regalia of those traditional rulers, but also questioning perhaps the ways in which their role now has been sidelined or that some of these traditions have been somewhat forgotten.

They’re not costumes, they’re not models. The fact that they might seem almost like theatrical stage images is a testament to kind of historical grandeur and majesty of these traditional monarchs that still hold an important role today.”

Khadija Saye, Andichurai, “in this space we breathe” (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Osei Bonsu: “Khadija Saye was an artist who tragically died very young. But rather than focusing on the circumstances surrounding her death, we really wanted to show her contribution to the landscape of contemporary African photography.

An artist of Gambian/British heritage, Khadija’s work is testament to her mixed faith upbringing, with a Muslim father and a Christian mother. These images are an attempt to ground herself within that spiritual understanding of her own identity through the traditional Gambian rituals.

It’s a tribute to her ancestral background and faith through photography. She used a wet collodion tintype process, which was popularized in the 19th century and is rarely practiced any longer. It’s a labor intensive process that leaves much to fate and to chance.

When the artist spoke about the experience of working this way, she related it to kind of spiritual transcendence in which the process becomes somewhat of a kind of a means of surrendering to the chemical outcome. The process captures these very irregular and almost kind of ghostly presences of herself.”

Zina Saro-Wiwa, from “The Invisible Man” (2015). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Osei Bonsu: “Zina Saro-Wiwa is an artist of Nigerian heritage who is based in the U.S., but grew up in the U.K. She worked as a journalist and is widely recognized for her work as a filmmaker and as an artist.

In “Invisible Man,” you see the artist reckoning with the her experience of loss in her own family, notably the death of her father, a climate activist and Nobel Prize nominee. She is posing in these photographs in a mask, because when one puts on a mask, you enter a realm between the living and the ancestral world.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, masks became very desirable objects, both as objects of ethnic culture and for the avant garde. But these masks were part of the way that African people related to their environment, the cosmos, to their ecosystems, and are still part of a living culture. The mask still has a very particular relationship to environment and to the way people relate to the ecosystem, which is under threat due to ongoing extractive practices particularly in relation to oil.

There’s a beautiful quote on the artist’s website saying that she was told that these masks were too heavy for women to carry. So, she had her own mask commissioned as a protest against this very gendered practice of excluding women from the politics of masquerade.

“Invisible Man” is one of the more poetic attempts for an artist to think about African history and cultural heritage, but really through their own lived experience.”

Sabelo Mlangeni, Miss Gay Ten Years of Democracy, Bheki Mndebele at Wesselton community hall (2003), “Country Girls.” Photo courtesy of the artist, ©Sabelo Mlangeni.

Osei Bonsu: “Sabelo Mlengani is a South African photographer who grew up in the province which is where the “Country Girls” series was shot. It’s a very personal reflection of LGBTQ life within the South African countryside.

We often associate these queer lives with kind of cosmopolitan environments, but there are also queer people who fashion their own identities within the countryside. The artist makes his subjects visible through these very intimate family portraits that both celebrate the kind of communities that are portrayed, but also think about their precarity and the vulnerability.

What he does by looking at this community is to upend or challenge many of the assumptions that people have that this is a recent trend or it’s kind of Western import. Queer culture, queer subjectivity is actually part of everyday life and very much in the spirit of the country.

We’ve included the ‘Country Girls’ series in an area of the exhibition titled ‘The Family Portrait,’ because we often see more conventional or normative depictions of family. This was an attempt to think about a more expanded idea of family that had more to do with one’s chosen family rather than one’s biological family.”

Dawit L. Petros, Untitled Epilogue II Catania Italy (2016), “The Stranger’s Notebook.” Photo courtesy of the artist.

Osei Bonsu: “Dawit L. Petro is an artist, now based in Chicago, whose family migrated from East Africa to Canada. In this work, he’s thinking about the longer histories of migration and border crossing, and his own experience as an outsider in many contexts.

This series was created over a year-long period of traveling Africa to Europe along the Mediterranean coast, retracing the journeys of migrants seeking better lives—the kind of sites of journeys of border crossings that we know often end in tragedy.

In the photographs, taken in Sicily and Mauritania—sites of arrival and departure for migrants—the subjects are holding mirrors that [reflect] back to the viewer, revealing coastline, power lines, all of these kinds of liminal spaces beyond the reach of the camera. ‘Stranger’s Notebook’ is a meditation on the ways in which we often aren’t able to humanize those who are the statistics on the global news reel, whether it be the refugee crisis or successive forms of of economic migration around the world.

It’s an attempt to grapple with the complexities of what it means to represent a subject that is unrepresented. And it makes you think not only about the contemporary implications of migration, but the much longer interconnected history and relationship between Africa and Europe.”

“A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography” is on view at the Tate Modern, Bankside, London SE1 9TG, July 6, 2023—January 14, 2024.

More Trending Stories: