Art & Exhibitions

How teamLab’s Post-Art Installations Cracked the Silicon Valley Code

This is what disruption looks like, as applied to the art experience.

This is what disruption looks like, as applied to the art experience.

Ben Davis

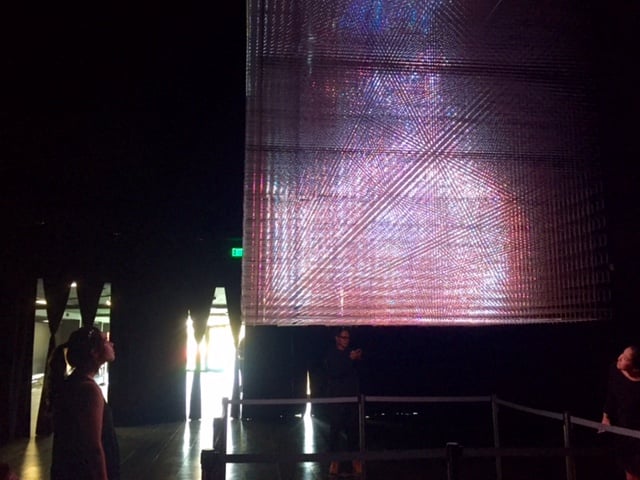

What do you say, as an art critic, about a sculpture that is a floating cube of LEDs, programmed to shimmer in a pattern resembling a living flame—essentially a 3D version of one of those video fireplaces? Or a passageway of lights that allow you to control their glittering patterns via smartphone?

Here’s one reaction: “This is not art.”

That is Pace gallery dealer Marc Glimcher’s own account of his initial take on the work of teamLab. In these blasé days where anything goes, you don’t hear that sentiment a lot. And, indeed, Glimcher had a rethink and decided that the Japanese art group’s polished, possibly post-art installations were just the thing for Pace’s attempt to finally win the attention of Silicon Valley’s heretofore art-indifferent moguls.

Exterior of Pace Art + Technology. Courtesy of Ben Davis.

Visiting San Francisco recently for the opening of the rebooted SFMoMA, I stopped by the teamLab show in Menlo Park, dubbed “Living Digital Space and Future Parks.” Featuring 20 installations, Pace’s teamLab exhibition is engineered to be a slightly different type of gallery experience; for starters, entry is by timed ticketing. The show has a main section, and then a children’s annex, featuring eight interactive experiences geared towards the little ones—fun for all ages.

At some point, if an art group grows big enough, it probably crosses over from being a “collective” to being a corporation. With a cadre of 400-plus self-described “Ultra-technologists,” teamLab has arguably crossed that line.

In a mainly positive review of teamLab’s recent show at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, the Boston Globe’s Sebastian Smee nevertheless laments that the group’s imagery “feels clichéd and sentimental, while its stated themes—nature and humanity—are perhaps unhelpfully vague.” I’d reply, in the parlance of Silicon Valley, that those qualities are a feature, not a flaw.

Takashi Kudo, one of teamLab’s principals in Tokyo, has described his originating insight for the group as coming from a trip to the Louvre, and the unpleasantness of being jostled by people jockeying to get a picture of the Mona Lisa. “The relation between art and people was one-by-one,” he has explained. “[teamLab’s] artwork makes viewing collaborative.”

Installation view of teamLab’s Light Sculpture of Flames. Courtesy of Ben Davis.

Here, the relationship is many-to-many; from teamLab’s army of designers to the masses. It’s industrial-strength art specifically engineered for the swarming experience culture has become in the age of mass tourism. (Pace is also betting on Random International, the design group behind the wildly-popular “Rain Room” experience.)

For the most part, teamLab’s work lives up to this promise. An attendant at the entrance to the show-stopping centerpiece, Crystal Universe—the interactive passageway of shimmering LEDs—makes sure that too many people don’t filter through at once. Even so, it was glitchy when I took my turn, the mobile site you access to control the lights via smartphone having only erratic effect on what I was experiencing. It appeared that too many people were cramming through at once, and overloading the installation’s sensors.

Still, there’s good reason to imagine that “Living Digital Space and Future Parks” is a smart bet for cracking Silicon Valley. “This is a community that is not very retrospective,” SFMoMA director Neal Benezra told me in an interview during the opening of the grand new museum. “They don’t want to hear about what you’ve done in the past, they want the next big idea.” Asked if Silicon Valley had thrown its money behind the museum, Benezra said, bluntly, no: “It’s often misunderstood that tech industries are suddenly supporting all the cultural institutions.”

Benezra chalked this reluctance up to the relative youth of tech’s world-conquering moguls. My own feeling is that Silicon Valley’s big players already consider themselves, in effect, artists. They are celebrated as visionaries and conversant with some very sophisticated cultural forms, but unencumbered by art’s niceties. What do the funky, “retrospective” pleasures of museum-art have to offer when you yourself are the next big thing?

The teamLab experience offers a possible response. Its aesthetic seems tailor-made to speak to an audience steeped in the language of user experience design and scalable engagement. A representative for teamLab says that the show hit 65,000 visitors in its first three and a half months (the gallery initially projected 30,000 for the run). If one is to believe the Wall Street Journal, despite being outwardly not-for-sale, the gallery has managed to sell a few installations for between $100,000 and $450,000.

Installation view of the children’s section of teamLab’s show at Pace Art + Technology. Image: Ben Davis.

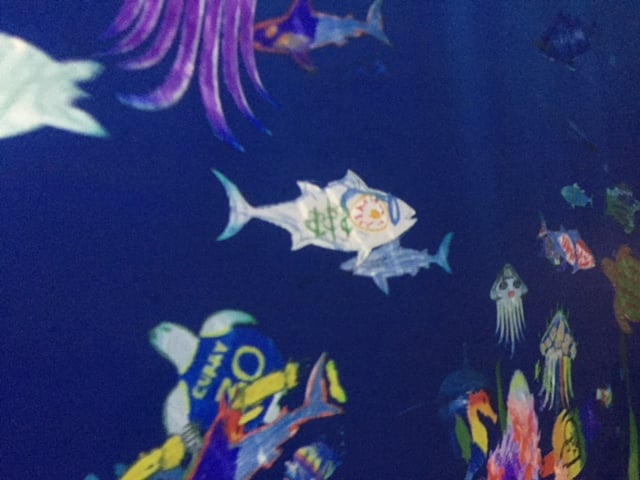

Over in the children’s section of “Living Digital Space and Future Parks,” you will find an interactive game of hopscotch, a wall-filling installation of animated Japanese characters that blossom into animals when you touch them, and a giant projection of a cheerful undersea world, among other things.

For the latter, kids can design their own sea creature on a piece of coloring paper, scan it into a machine, and watch it appear immediately in the animation and swim around.

The author’s own fish in teamLab’s Sketch Aquarium. Courtesy of Ben Davis.

It’s telling that the kids’ stuff here feels like it lives up to the promise of the show’s interactive art the best.

As one matures, you learn to define a self and to engage with others as individuals rather than as simply extensions of your own needs and desires. In short, you learn to have “one-to-one” experiences rather than “many-to-many” experiences. The teamLab aesthetic, on this level, represents deliberately managed cultural regression.

Back in the main building, the more “adult” fare includes works like the seven-screen, elaborately named Crows are Chased and the Chasing Crows are Destined to be Chased as Well, Division in Perspective—Light in Dark. Bathing you in bombastically heroic videogame-style music and dazzling images of magical birds transforming into flowers, this work is spectacular but not exactly deep. So, even at its most grown-up, teamLab-style art might be thought of as of a piece with other cultural phenomena of the moment, such as the cinema’s obsession with the superhero blockbuster, with its flashy special effects and broad-brush themes.

But, hey, I’m not going to pretend like I’m immune to the charms of a good superhero flick, or a bit of interactive fun. Criticizing the pleasures of teamLab’s post-art art may be a bit like criticizing the appeal of staring at blinking lights. Sometimes it’s exactly like that, actually.

If you get a chance, do go see this show. It gives you a glimpse of what Silicon Valley disruption looks like, as applied to the art experience.

teamLab, “Living Digital Space and Future Parks” is on view at Pace Art + Technology, Menlo Park, through July 1, 2016.