Art World

Here Are Five of the Most Fascinating Works of Art at TEFAF New York Spring

From the long historical reach of Oceanic art to bronze Roman statuary, TEFAF specializes in art that tells a story.

From the long historical reach of Oceanic art to bronze Roman statuary, TEFAF specializes in art that tells a story.

Rachel Corbett

The first thing you see when you walk into this season’s edition of TEFAF New York is a fresh-from-the-studio John Currin painting of a bare-chested blonde, on view at Gagosian Gallery’s booth. It’s not the kind of work historically associated with the esteemed Dutch fair, which was launched in Maastricht in 1988 with an emphasis on Old Masters and antiquities.

But this year’s event, which runs from May 4 through 8 at the Park Avenue Armory, is chock full of contemporary art and blue-chip American dealers, including first-time participants Gagosian and Marian Goodman. Early reported sales include a 1982 Jean-Michel Basquiat painting at Lévy Gorvy with an asking price of under $5 million, two works by Josef Albers at David Zwirner for $1.75 million and $750,000, and a late Philip Guston painting from 1979 priced at $5.5 million at Hauser & Wirth.

The Dutch import debuted in New York in 2016 with two editions: fall (with an emphasis on Old Masters) and spring (with an emphasis on blue-chip Modern and contemporary). While heavy on mid-century Modernism and Impressionism, this year’s event still boasts a healthy dash of furniture, jewelry, and antiquities.

Since TEFAF has always specialized in art with a history, we hunted down five works that have revelatory back stories.

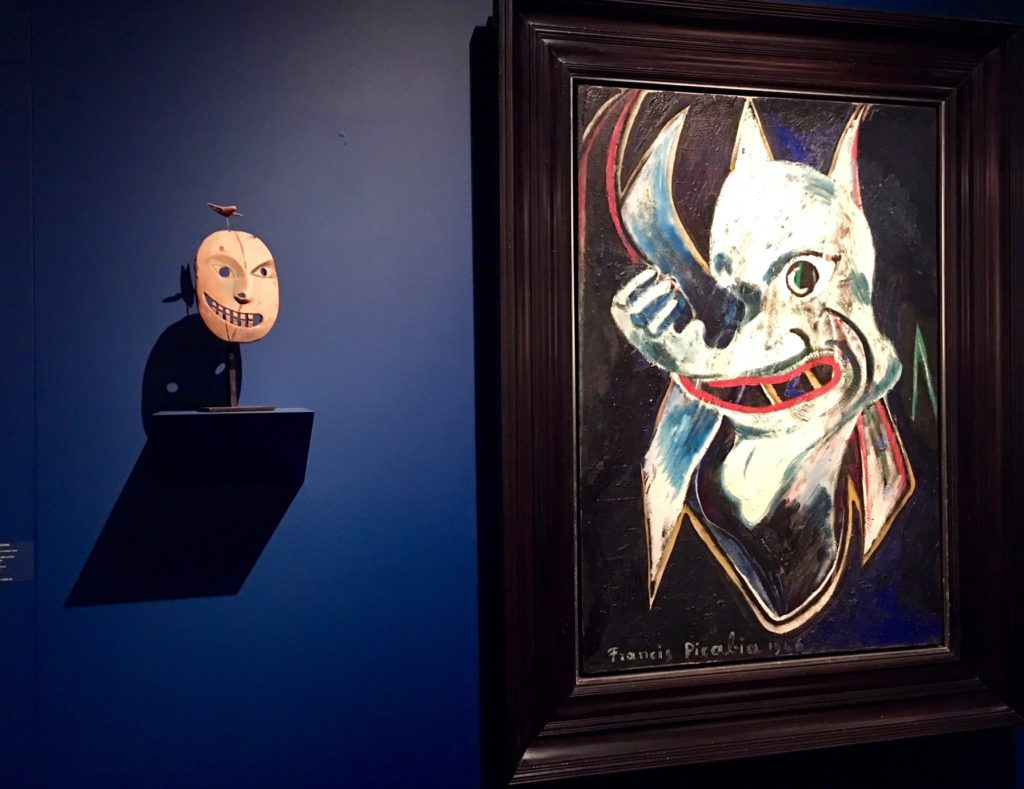

Left: A wooden mask from the Yukon river region of Alaska (ca. 1890–1910). Right: Francis Picabia, Monstre (1946)

Left: A wooden mask from the Yukon river region of Alaska (ca. 1890–1910). Right: Francis Picabia, Monstre (1946)

The French artist André Breton once owned the Alaskan wooden mask (ca. 1890–1910) that Di Donna gallery paired alongside one of Francis Picabia’s monster paintings in its themed booth at TEFAF. Surrealist artists long admired these Yup’ik masks from the central Alaskan coast, which were made in the hopes of divining bountiful hunts, according to gallery director Christina Floyd Di Donna. Breton, Man Ray, and Yves Tanguy all collected the masks beginning in 1934. “They saw it as Surrealism from another time and place,” she said. An extended exhibition of Surrealist painting paired with Yup’ik masks, titled “Moon Dancers,” is on view through June 29 at Di Donna’s gallery in New York.

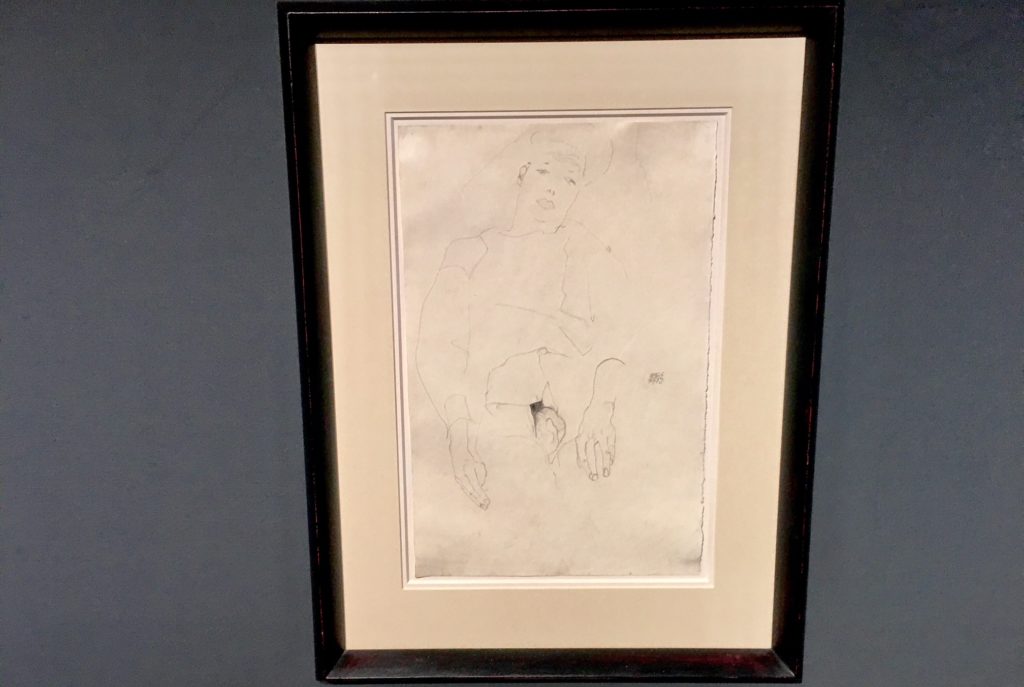

Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait (1912)

In 1912, the Austrian artist Egon Schiele spent 28 days in prison for exposing a young girl to the nude drawings he had pinned up in his studio. Although he was acquitted of the more serious charge of statutory rape, he was found guilty of exposing his pornographic work to a child. To occupy his time in jail, he sculpted a head out of bread. When his lover finally brought him art supplies, he began to draw his cell and the objects in it. He titled one watercolor drawing of an orange, “The single orange is the only light.” He then moved on again to his preferred genre, self-portraiture, but, because he didn’t have a mirror in his cell, he had to do them entirely from imagination. The director at the Vienna gallery Wienerroither & Kohlbacher didn’t know whether this particular drawing was done in prison or not—apparently those works are rare in the market—but he agreed that the artist looks miserable enough to make it possible.

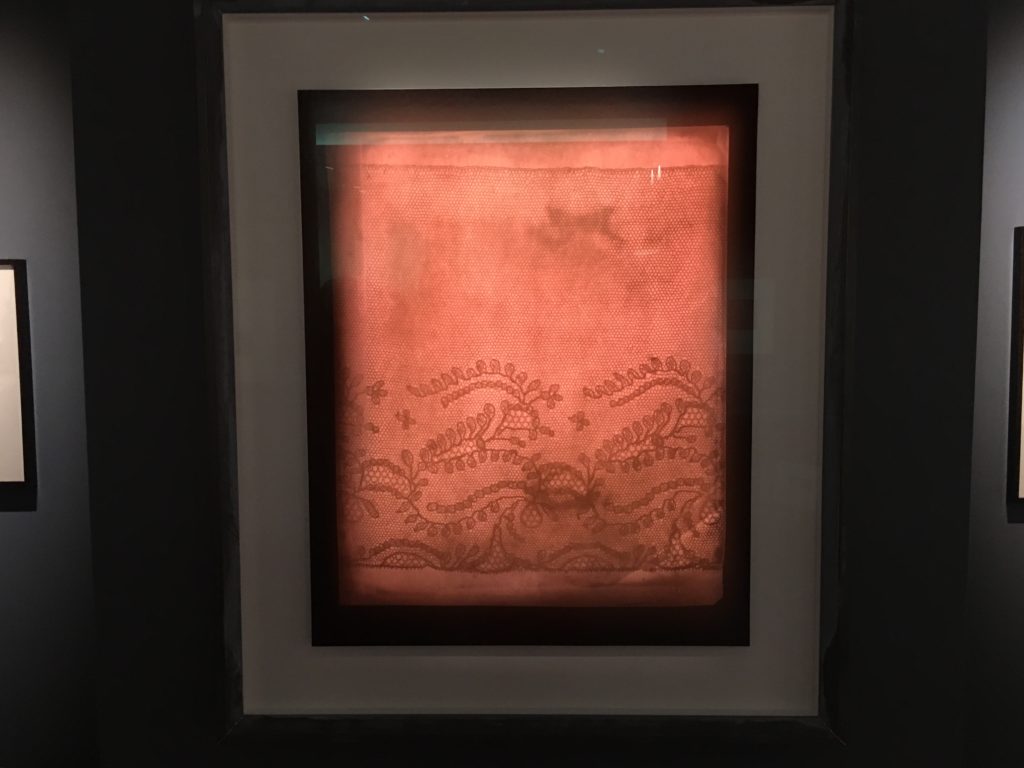

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Photogenic Drawing 008, Lace, c. 1839 (2008)

A mini-survey of the history of photography is on view at the booth of Hans P. Kraus Jr. Fine Photographs. The New York gallery is showing a fine salt print from the early 1840s by William Henry Fox Talbot, a scientist and pioneer of photo technology, who famously put a piece of lace on photographically-sensitized paper. The resulting image astonished viewers, who thought they were looking at actual lace rather than a photograph. Fast forward 150 years and you have the Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto, who bought up a number of Talbot’s tiny unprinted negatives and then rephotographed and enlarged them. “Photography is like a found object,” Sugimoto once said. “A photographer never makes an actual subject; they just steal the image from the world.” The stand also includes rare prints by early photographers like Gustave Le Gray, Duchenne de Boulogne, and Louis Robert.

A large votive figure and a pregnant effigy, both from Alaska, at Galerie Meyer Oceanic and Eskimo Art

Like Di Donna’s pairing of Surrealists with Yup’ik masks, Paris’s Galerie Meyer, which specializes in Oceanic and Eskimo art, looks at the tribal works that influenced Dadaist artists. A suite of drawings of female nudes by German artist George Grosz lines one wall, while wooden figures, including of a pregnant woman and a kangaroo mother, by Oceanic and Eskimo artists populate the other. Grosz wasn’t himself known to be a collector of Oceanic art, “but he had his eye on it,” gallery owner Anthony JP Meyer said. “Dada is intricately entwined with tribal art. “We wouldn’t have this,” he said, pointing to the Grosz works, “without that.”

Henri Matisse, Figure assise et le torse grec (la gandoura) (1939)

This painting at Hammer Galleries’s booth gives an intimate look inside Henri Matisse’s new studio in the Hotel Régina in Nice in 1939. The figure has no face, though it’s likely that it wasn’t his wife, whom he was about to divorce, or his longtime assistant and model Lydia Delectorskaya, who he had had to fire at the wishes of his wife. Critics have pointed out that this painting reveals the Ottoman influences that were shaping Matisse at this phase in his life through the “gandoura” robe worn by the model and the philodendron in the background. It also gives us a glimpse into Matisse’s own collecting habits, with the view of a Roman replica of a Greek torso in the back.