Opinion

The 100 Works of Art That Defined the Decade, Ranked: Part 3

In the third installment of a four-part series, our critic reveals his picks—number 50 through number 26—of the key artworks of the 2010s.

In the third installment of a four-part series, our critic reveals his picks—number 50 through number 26—of the key artworks of the 2010s.

Ben Davis

This is the third part of a series looking at the art of the 2010s. The other parts are here, here, and here.

A view of the Oakland exhibition of the Museum of Capitalism. Photo by Cinque Mubarak, courtesy Museum of Capitalism.

An authentically viral project, based on a good idea. Seeing an unused space in Oakland, Timothy Furstnau and Andrea Steves, aka Fictilis, asked the question: “What would a Museum of Capitalism look like, if we were to look back on just how strange our present system is from the point of view of a future where it had passed into history?” They invited artists to contribute exhibits to the fictional museum, and the results have spawned a whole touring educational eco-system of its own.

Colossus at the entrance of Damien Hirst’s “Treasures From the Wreck of The Unbelievable.” Image courtesy Ben Davis.

There is plenty to question and criticize in Damien Hirst’s vast, involved, ultra-high-production show in Venice, featuring endless chambers of imagined treasures, presented as if they were a hoard from a shipwreck, complete with a diorama of the wreck and even a fake Netflix documentary. But give credit where credit is due: unlike many artists with his level of fame, the guy hasn’t stood still, with “Treasures From the Wreck of the Unbelievable” raising the bar for the level of sheer, interconnected myth-making you need to stay ahead of the game.

Duke Riley, Fly by Night (2016). Courtesy Creative Time/photographer Tod Seelie.

Riley choreographed swarms of pigeons with LED lights affixed to them to offer a thoroughly delightful civic spectacle, building off the artist’s love of urban esoterica, in this case his affection for the Big Apple’s tradition of rooftop pigeon keepers.

Anthea Hamilton’s exhibition at the Turner Prize 2016. Courtesy Joe Humphrys ©Tate Photography.

It is described, wonderfully, as “a large backside (or ‘butt’) inspired by a photograph showing a model by Italian designer Gaetano Pesce.” Originally seen at the SculptureCenter in New York, Hamilton’s sculpture is one of the most memorably wacky things ever to be nominated for the Turner Prize.

Jordan Wolfson’s (Female Figure) (2014) at David Zwirner gallery. Photo by Artnet News.Photo: artnet News.

It has a a nasty edge, but Wolfson’s witch-masked robot stripper, which literally stares back at the viewer as it gyrates in a mirror, is undeniably unnerving. Realized by state-of-the-art Hollywood special effects house Spectral Motion for a reported half-million dollars, with capital fronted by David Zwirner gallery, (Female Figure) set a high-water mark for artists working with robotics.

Ann Hamilton’s The Event of a Thread at the Park Avenue Armory. Image courtesy Park Avenue Armory.

The Park Avenue Armory’s specialty in big art was one of the major forces of the decade. It’s hard to do justice to that kind of space while also doing something thoughtful and poetic—and Hamilton’s elegant piece did just that.

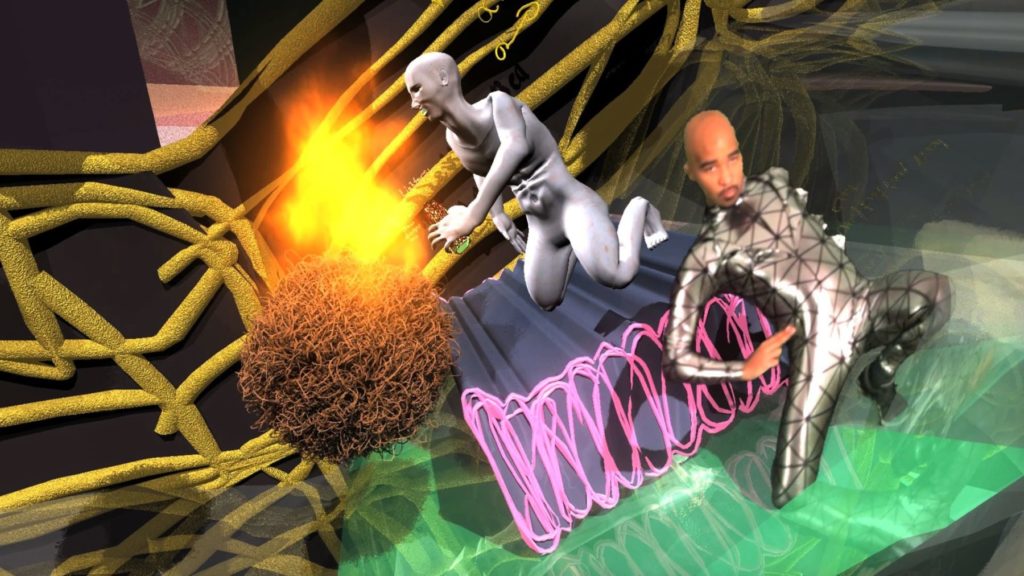

Jacolby Satterwhite, Reifying Desire 5 (2013). Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

Satterwhite’s mother had schizophrenia and coped by making drawings of imaginary products inspired by TV commercials. For his star-making series of animated videos, the artist gives life to those ideas and animates his own body into the resulting digital world, using virtual space as a forum for candy-colored, liberated possibilities.

Simone Leigh, Brick House at the “spur,” the last section of the original structure of the High Line to be converted into public space in New York. Photo courtesy of the High Line.

The work chosen to inaugurate the High Line’s public sculpture commission was also the most ambitious realization of Leigh’s ongoing “Anatomy of Architecture” series. As a description explained, the title of the 16-foot-tall monument “comes from the term for a strong black woman who stands with the strength, endurance, and integrity of a house made of bricks.” The artist’s distinctive iconography of calm and centeredness manages to project this sense, miraculously, amid the bustle.

Korakrit Arunanondchai, No history in a room filled with people with funny names 5 (2018). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Trance-like and brimming with intense, indescribable emotion, Arunanondchai’s work crams a year of human experience into one symbolic space, flickering from a narrative about the artist’s mother’s dementia to a laser-studded performance by boychild, the transcendent gender-nonconforming performance artist, to news from the 2018 Tham Luang cave rescue. Seen at the apocalyptic Venice Biennale earlier this year, it gives an overpowering sense of a world where levels of emotional reality—pleasure and pain, celebration and despair—are collapsing into each other.

Moyra Davey, Les Goddesses (2011). Image courtesy the artist.

Erudite, intimate, and influential as a model of how to be personal while breaking out of a certain narcissism, Davey’s Les Goddesses is an experiment in autobiography, trying to find a way to engage with “unspeakable memories” via the device of the artist weaving together the details of her own life and the details of the life of early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft.

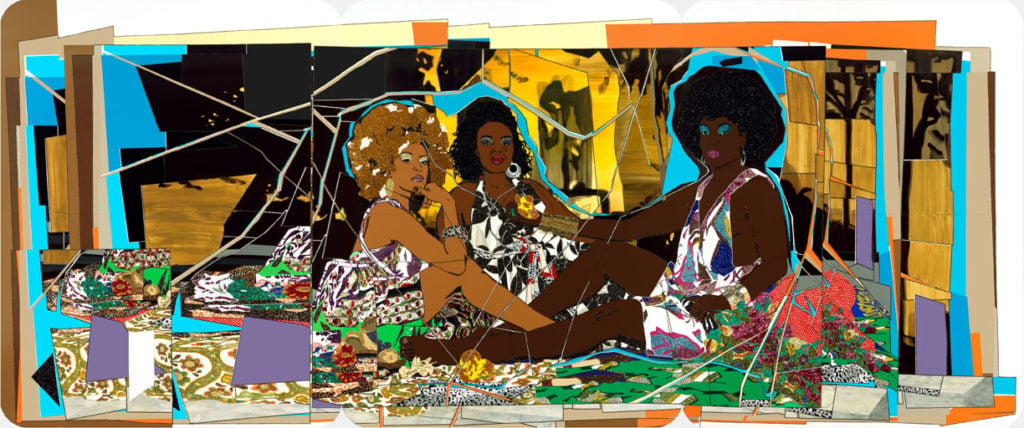

Mickalene Thomas’s Le Déjeuner sur L’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noir (2009). Image courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin Gallery.

Begun as a commission for MoMA, Thomas’s confidant rhinestone, acrylic, and enamel reclamation of Manet’s famous picnic as a stage to center black beauty has found a huge audience.

Camille Henrot, Grosse Fatigue (2013). Image courtesy the artists and the Guggenheim.

The story of the universe, told from the point of view of images shuffling across a desktop; Cosmos meets desktop cinema.

Installation of copies of Indigenous Woman at RYAN LEE Gallery. Image courtesy the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery.

Gutierrez’s great idea was to create a fictional 126-page glossy fashion magazine dedicated to “Mayan Indian heritage.” For the project, she plays art director, model, and editor (and, less glamorously, as she told Vice, “also the crew. I’m the schlepping person”). This allowed her to explore different nuances of identity “as a woman, as a transwoman, as a latinx woman, as a woman of indigenous descent, as a femme artist and maker” in a fun, outspoken way. Images from the project made Gutierrez a break-out at the 2019 Venice Biennale as well.

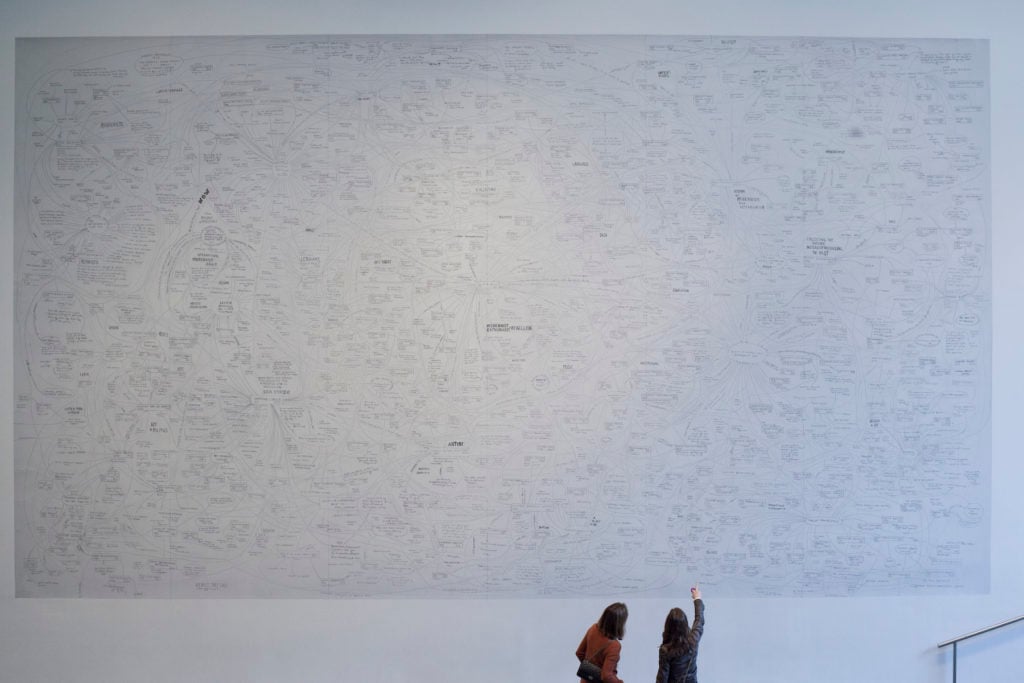

Installation view of Andrea Geyer’s Revolt, They Said (work in progress) at the Museum of Modern Art, 2015. Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

Geyer’s wildly ambitious graph detailing all the affiliations and relationships of some 850 women who helped define modern culture is tremendous as a work of research, but also swarms with graphic energy.

Random International’s “Rain Room” displayed at the Yuz Museum in 2018. Photo courtesy of the Yuz Museum.

These design-artists’ precision-engineered interactive wonderground offered one of the major, crowd-courting museum attractions of the era. Could anyone have guessed just how much museum-goers hungered to be in a storm but not get wet?

Does McNitt’s virtual reality trilogy count as immersive cinema or art installation? “VR experiences” collapsed those strands into one, and Spheres is the most convincing thing I saw in this much-explored category. I could quibble with how it fudges the science that it purports to make concrete, or whether its use of breathy voiceover (from Jessica Chastain, Millie Bobby Brown, and Patti Smith) doesn’t skip over lingering problems with holding attention in the medium. But as pure experience, I still remember Spheres’s rendering of being sucked into the depths of a black hole or of floating through the solar system, across the rings of Saturn, and towards the Earth. Pretty far out.

Alex Da Corte, Rubber Pencil Devil at the Venice Biennale in 2019. Image courtesy the artist and Karma.

Seen at the Carnegie International and then at the Venice Biennale, this eerie, 57-part anthological video work features the artist giving scabrous, nightmarish life to a variety of personae from pop culture, from Bart Simpson to Mr. Rogers to a Heinz Ketchup bottle. Rubber Pencil Devil is like being dragged behind a boat along the rocky bottom of someone’s junk-strewn mind.

Installation view of Cameron Rowland, Attica Series Desk (2016) at Artists Space, 2016. Photo: Adam Reich.

Recharging the severity of classical Conceptual art, Rowland’s desk presented an object manufactured by Corcraft at Attica Correctional Facility, displaying the results of inmate labor unadorned so as to stress the everydayness of the objects that it produces and thus how the structure of mass incarceration is part of the everyday reality of US life. One of its most important aspects is invisible (except when reading about it), which is the way that it also makes the economic relations around itself part of its meaning: It is not sold. Instead, it “may be rented for 5 years for the total cost of the Corcraft products that constitute it.”

Still from Chris Johnson and Hank Willis Thomas, Question Bridge: Black Males (2012) Image courtesy the artists.

Based on conversations with 150 black men from a variety of backgrounds in 12 cities, Johnson’s and Thomas’s innovative transmedia art project edited together 1,500 video exchanges into a video installation/conversation in which their subjects appear to be interrogating one another. It toured more than 30 different institutions, and also lives on as a book, a website, and a curriculum.

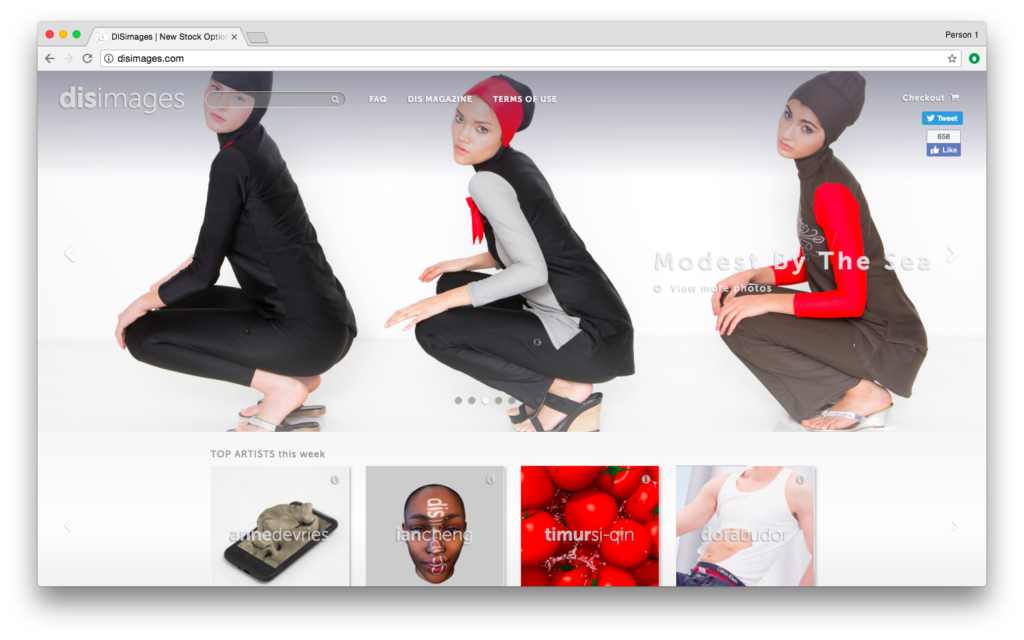

Screenshot of DIS Images, 2013. Image courtesy DIS.

The oddball corporate surrealism of DIS (aka Lauren Boyle, Solomon Chase, Marco Roso, David Toro, plus sundry collaborators), which launched this initiative to create an online archive of artist-designed stock image photos, sort of defined a moment (what Christopher Glazek called “Generation DIS.”)

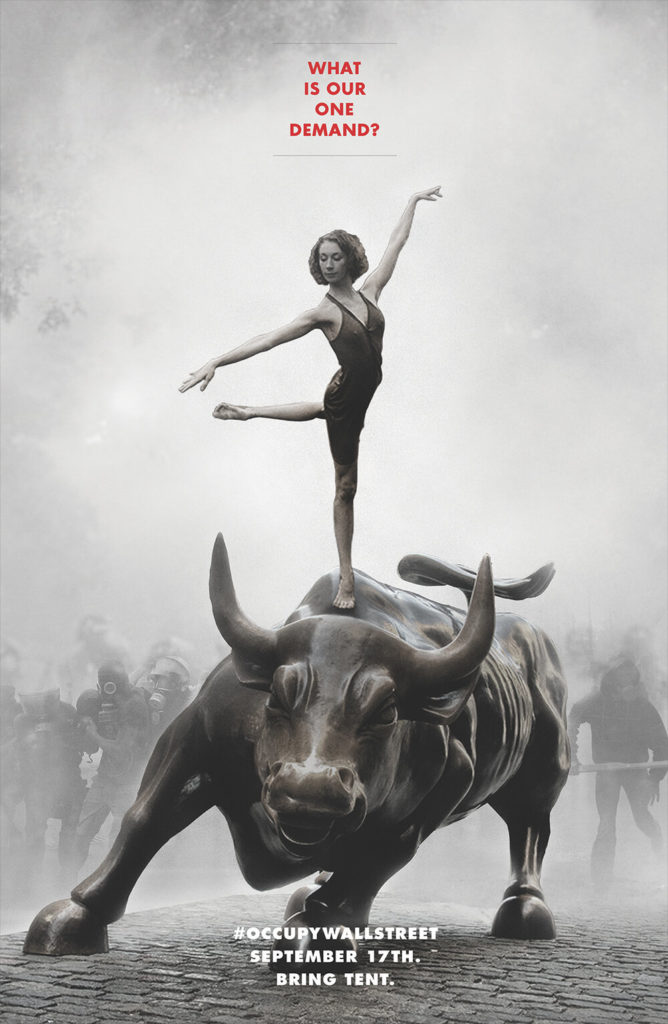

Adbusters poster, July 2011.

“There was some magic about it,” Adbusters editor Kalle Lasn said of the image of the ballerina twirling atop Wall Street’s Charging Bull sculpture amid clouds of teargas. This romantic, even whimsical graphic is probably the artwork most associated with Occupy Wall Street. It hit the hopeful note of reawakening what you thought was possible of that moment.

Hiroon Mirza, stone circle in Marfa. Image courtesy the artist and Ballroom Marfa. Photo by Emma Rogersm, courtesy of hrm199, Ballroom Marfa, and Lisson Gallery.

Mirza’s mighty “solar-powered Stonehenge” in the West Texas desert is designed to “activate” itself on the full moon, coming to life with LED lights and spacey electronic sounds (you can hear snippets of it here). It’s a monumental mixture of ancient and contemporary. As a side note, it seems to have intensified local interest in solar power.

Image from Damon Davis, All Hands on Deck (2015). Image courtesy Museum of the artist and Contemporary Art, San Diego.

St. Louis-based Davis’s idea, hatched in the wake of the rebellion in Ferguson, seems simple: take pictures of multiple hands, raised in the “don’t shoot” gesture that became a symbol of that movement, and wheat-paste these on buildings boarded up in the wake of the protests (they were also taken up in various other cities and shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego in 2016). The zoomed-in emphasis on the individuality of the various hands stood as a kind of symbol of the social depth of Black Lives Matter demonstrations, a way to visually cut against dehumanization and claim solidarity. (It persists as a digital archive.)

Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of Barack Obama at its unveiling at the National Portrait Gallery. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Definitely one of the signal art events of the decade, even if I have my questions about it.

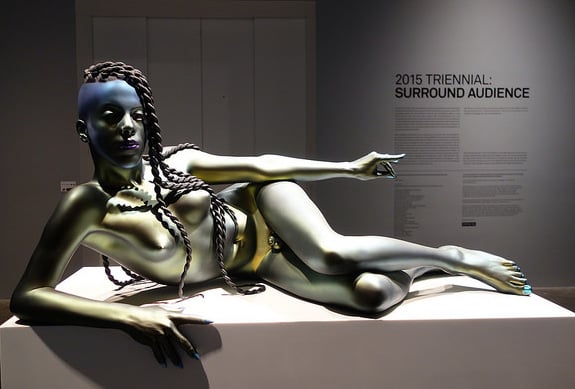

Frank Benson, Juliana in the New Museum Triennial. Image: Ben Davis

Referencing classical sculpture in its pose and a future-is-now sensibility in its “digital machine finish,” Benson’s hyper-detailed, 3D-scanned sculpture of Juliana Huxtable, the multi-talented artist and performer, was claimed as a symbol of transgender pride after its presentation at the 2015 New Museum Triennial. It’s also just a commanding work of art.