People

The American Painter Wayne Thiebaud, Who Transformed Cakes Into Symbols of Joy and Longing, Has Died at 101

Thiebaud, who spent most of his life in California, was one of the country's most beloved and recognizable painters.

Thiebaud, who spent most of his life in California, was one of the country's most beloved and recognizable painters.

Julia Halperin

Wayne Thiebaud, whose luminous paintings of cakes, gumball machines, and other symbols of mid-century Americana made him one of the country’s most recognizable and beloved artists, died on Saturday, December 25. He was 101.

His death was confirmed by his gallery, Acquavella in New York.

Thiebaud worked as a graphic designer and cartoonist before he set out to pursue a career as a painter in the mid-1950s. He rose to prominence as Pop art entered the mainstream, but his approach to the iconography of American life was distinct from that of peers such as Andy Warhol and James Rosenquist: less critique and satire, more nostalgia, joy, and longing.

Thiebaud drew as much from Abstract Expressionism as Pop art, applying paint thickly with a palette knife in the same way a baker frosts a cake. His art also invited comparisons to Edward Hopper, who infused snapshots of American life with pathos, and Giorgio Morandi, the Italian artist who painted simple bottles as if they were icons (and whose works Thiebaud collected).

Wayne Thiebaud, Pies, Pies, Pies (1961). Courtesy of the Crocker Art Museum, gift of Philip L. Ehlert in memory of Dorothy Evelyn Ehlert, ©Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at ARS, New York.

In the end, Thiebaud was one of a kind. Unlike many artists of his stature, he did not consider commercial art or illustration to be a lower form of expression. Pretension, to him, was a waste of time. Proust used language to transform the humble madeleine into a weighty symbol of melancholic yearning; with paint, Thiebaud unleashed similar alchemy on a slice of lemon meringue pie (his favorite).

“He was a brilliant artist, and his work will forever encourage us to see our world in a more textural light, where common objects can ascend to profound and iconic heights,” said Gary S. May, the chancellor of the University of California, Davis, where Thiebaud taught for more than 40 years.

Thiebaud was born to a Mormon family in Mesa, Arizona, in 1920. Growing up on a farm during the Great Depression, he helped his father by milking cows, shooting deer, and planting greens, according to an account from the New York Times. His uncle Jess was an amateur cartoonist, fostering his love of narrative imagery at a young age.

When Thiebaud was a teenager, his family moved to Long Beach, California. (Thiebaud eventually left the Mormon Church.) During one influential summer break, he worked as an apprentice animator at Disney. He went on to find jobs as a sign painter, cartoonist, fashion illustrator, and theater designer. During World War II, he served as an artist in the U.S. Army’s First Motion Picture Unit.

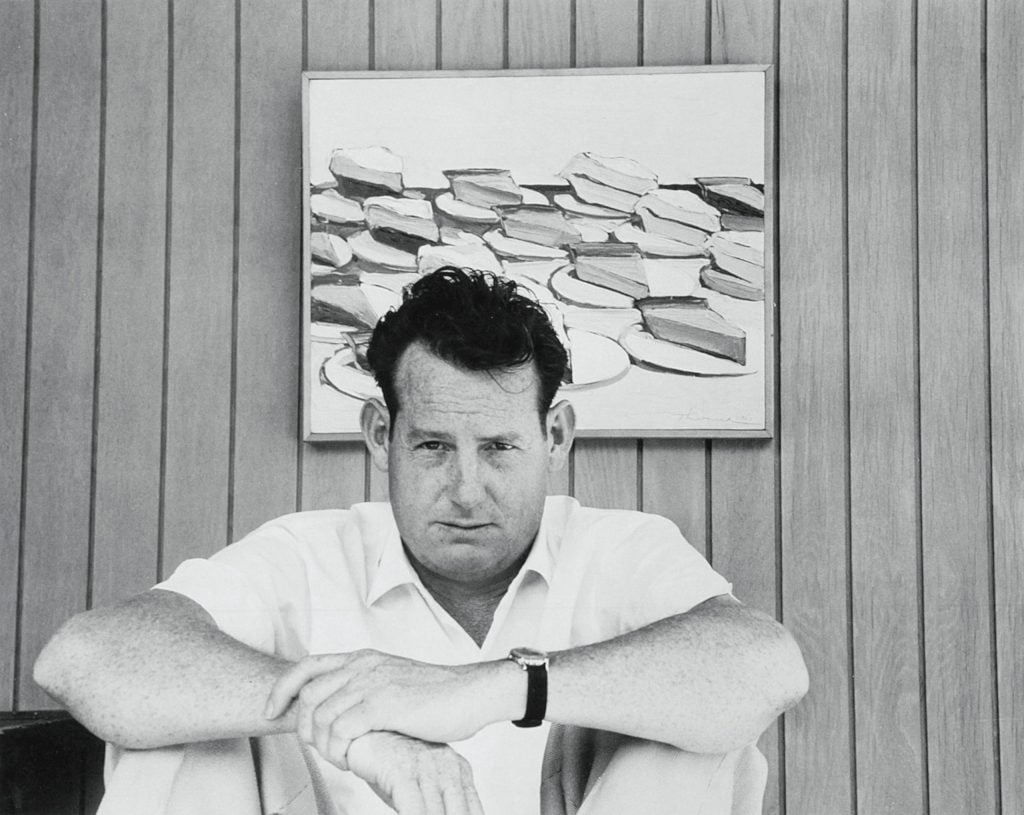

Wayne Thiebaud at home in Sacramento in 1961. Photo by Betty Jean Thiebaud. Artwork ©Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

His instincts as a teacher were evident even then, as he began teaching life drawing to fellow servicemen. Under the G.I. Bill, he went on to earn his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine arts at Sacramento State College (now California State University, Sacramento), where he later taught.

In the late 1950s, Thiebaud began to find his footing as a painter. On trips to New York, he rubbed shoulders with the likes of Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and dealer Allan Stone, who would go on to become his gallerist for decades. His breakout solo show at Allan Stone Gallery in 1962 sold out and drew rave reviews. That same year, Thiebaud’s work was included in the influential Pasadena Art Museum exhibition “New Painting of Common Objects” curated by Walter Hopps. It is considered a landmark exploration of the emerging Pop art movement.

“Once I painted pies, I thought no one would be interested in them; it seemed like a silly thing to do,” Thiebaud told Artnet News in a 2020 interview. “But as I did it and got interested, I couldn’t leave it alone. I looked at all the other things that I thought had been overlooked.”

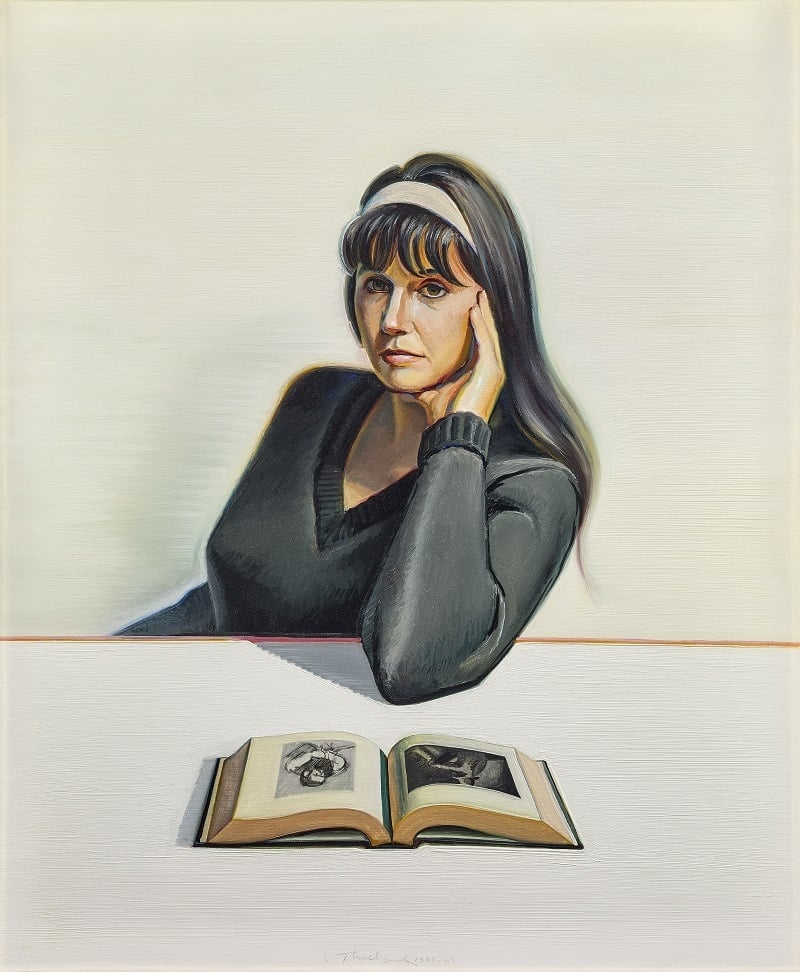

Wayne Thiebaud, Betty Jean Thiebaud and Book (1965–69). Courtesy of the Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Wayne Thiebaud, ©2019 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

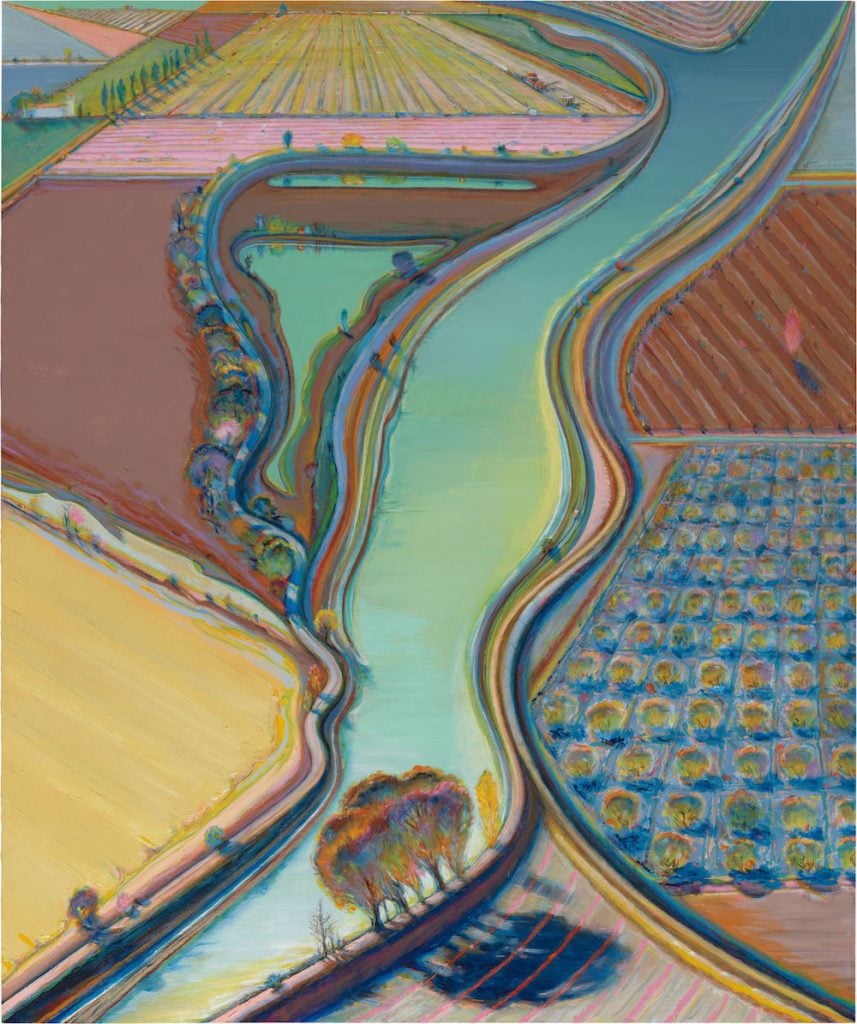

Over the next several decades, Thiebaud returned repeatedly to the subject of pies (and cakes, and cupcakes, too). He also painted portraits of women in bathing suits staring blankly at the viewer; rows of lipsticks resembling a city skyline; and sun-dappled San Francisco streetscapes. His practice of outlining objects with a ring of contrasting color lent them a halo-like effect, making it feel as if he were depicting a memory of the thing, rather than the thing itself.

In 1960, Thiebaud joined the faculty at U.C. Davis, where he would teach for the next four decades (and continue teaching even after his official retirement). His favorite course, he once said, was beginner drawing. An exhibition this spring at the university’s Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art demonstrated the breadth of his influence as an educator, featuring work by Andrea Bowers, Bruce Nauman, Robert Colescott, Alex Israel, and Jonas Wood, among others.

“Wayne’s work was a huge early influence,” Bowers told Artnet News. “I loved his brilliant use of color and composition with its joyful California vibe. I used his art in my classes for years to teach young artists. His work has had a huge impact on generations of artists and will continue to do so!”

Wayne Thiebaud Winding River (2002). Image courtesy Phillips.

Another former student, Jock Reynolds, who went on to become director of the Yale University Art Gallery, recalled in a 2010 New York Times interview that Thiebaud kicked off one of his courses with “a remarkably lucid lecture on where to buy the best and cheapest salami, cheese, coffee, fruit, bread, cakes, and wine, things he insisted would significantly enrich the quality of our lives.”

One of the most celebrated painters of his generation, Thiebaud represented the United States at the São Paulo Biennial in 1967, and was awarded the the National Medal of Arts by President Bill Clinton in 1994. He had solo exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1985), the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (2000), New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art (2001), the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento (2010), and the Voorlinden Museum in the Netherlands (2018).

Compared with many of his peers, Thiebaud has been a rare presence at auction. A new benchmark for his market was set last year when Four Pinball Machines (1962) sold at Christie’s for $19.1 million (estimate: $18 million to $25 million). No other canvas by the artist has fetched more than $10 million on the auction block, though his work has begun to gain more traction in recent months.

Wayne Thiebaud, Four Pinball Machines (1962). Photo courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd 2020.

Earlier this year, two of his paintings—a landscape and a portrait of a woman toweling her face—sold for $9.8 million and $8.4 million respectively, according to the Artnet Price Database. A selling exhibition, “Wayne Thiebaud: Cities, Sweets and Portraits,” is on view at Sotheby’s Palm Beach through January 2, 2022.

In his 2020 interview with Artnet News, which coincided with his 100th birthday celebrations, Thiebaud was asked to divulge his secret to a long and happy life. At the time, he was still regularly painting and playing tennis.

“I spend a lot of time in the studio,” the artist said. “I work almost every day. I have a wonderful family who indulges me in this amazing search for how difficult it is to make a good painting.”