Archaeology & History

The Hunt: Leonardo da Vinci’s Fabled Lost Mural

Is it lying in wait to be discovered behind a fake wall, or did the artist abandon it before he even really started?

Cerca, trove. “Seek and ye shall find.”

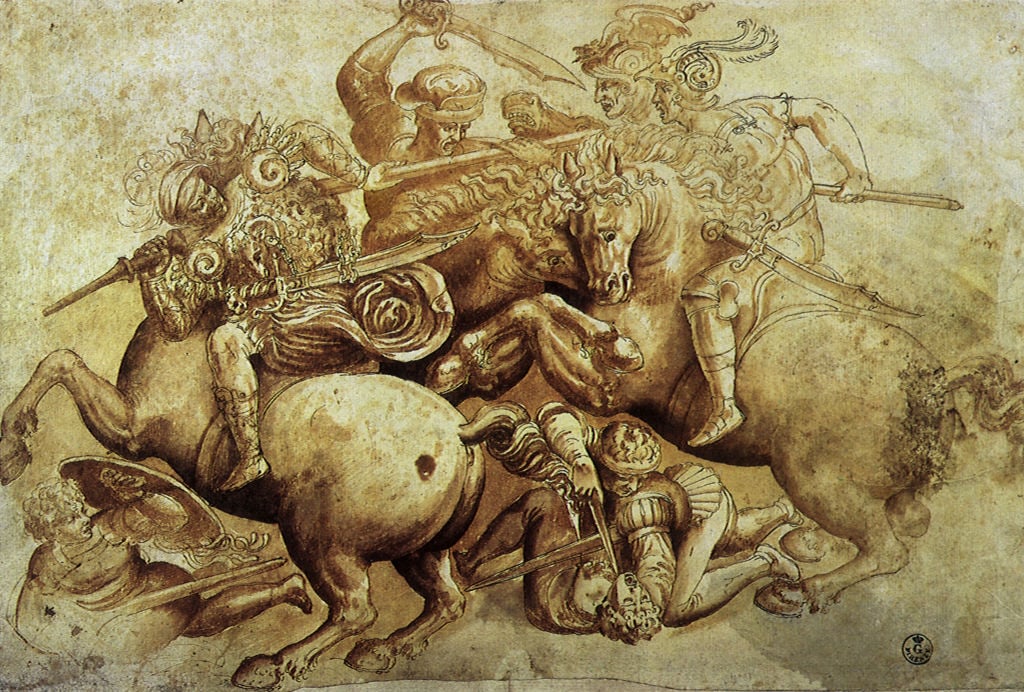

So reads a painted flag in a mural in Florence’s town hall, which one researcher is convinced is a clue to the location of one of art history’s great lost artworks: a major mural by Leonardo da Vinci. The Battle of Anghiari, from the first decade of the 16th century, was commissioned by statesman Piero Soderini and intended to glorify Florentine forces’ victory over Milanese troops in a 1440 battle.

But does it even exist? No one knows for sure.

It lives on in drawings by artists who admired it, including one by no less than Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens, now in the Louvre’s collection. But if today you visit the Palazzo Vecchio’s Hall of Five Hundred (a room built to accommodate the city council) and go to the spot where Leonardo’s mural may have been, you’ll see one from decades later by artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari, wherein the cryptic Cerca, trove message is tucked away.

Leonardo’s mural was supposedly left half-finished when he unsuccessfully tried to combine oil paint with the fresco technique. By 1555, power had changed hands to the Medici banking family; allied with the Milanese, they commissioned Vasari to paint a mural showing a victory over the Sienese instead, and Leonardo’s work was presumed to be destroyed. But Vasari was a big Leonardo fan, and may not have wanted to demolish the artist’s work; he even praised it highly in his book, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, first published in 1550.

Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci, by Lattanzio Querena. Padova, Medieval And Modern Art Museum. Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images.

Where things get very interesting is that this one wall, unlike the others, has a few-inch-deep cavity behind it. A team led by Maurizio Seracini, a researcher at the University of California, San Diego, drilled a few tiny holes in the wall (confining themselves to places where the mural had already been damaged and/or restored); inserting a microscope, they discovered behind it a black pigment that Leonardo also used in his masterpiece Mona Lisa as well as his St. John the Baptist, from the same time. And there are traces of a lacquer that would have been used on a painting but not an ordinary wall, Seracini says.

Why, he asked, would the town build another wall for Vasari’s mural, except to save something valuable behind it? And is Vasari’s “seek and ye shall find” a message to future historians seeking out Leonardo’s missing masterpiece, telling them they are looking in the right place?

(If this all sounds a bit like a Dan Brown novel, note that Vasari’s cerca, trove message did play a role in the convoluted plot of the Da Vinci Code author’s 2013 novel Inferno, another in the series devoted to Harvard symbolism professor Robert Langdon.)

Florence’s mayor, Matteo Renzi, wanted to have further drilling done, but Cristina Acidini, superintendent for the Special Superintendency for the Florentine Museum Complex, put the kibosh on his plan when she ruled out drilling more holes, and more than 100 experts signed a petition calling on authorities to stop work that, they said, would harm Vasari’s painting. Renzi shelved the project in response.

But there are those who say the search is all in vain. Art historian Francesca Fiorani of the University of Virginia, author of the 2020 book The Shadow Drawing: How Science Taught Leonardo How to Paint, for one, asserted that the mural was never even completed, and that the artist only got as far as unsuccessfully preparing the wall.

“We have lost a battle (of Anghiari),” she cleverly said at a 2020 press conference on the occasion of an academic publication including research on the mural, “but we have gained a consensus on scientific research which I would say is particularly welcome.”

So, who is right? And will a real-life Robert Langdon one day come along to solve this mystery? For now, we’ll have to wait, but maybe one day, he who seeks shall find.

The Hunt explores art and ancient relics that are—alas!—lost to time. From the Ark of the Covenant to Cleopatra’s tomb, these legendary treasures have long captured the imaginations of historians and archaeologists, even if they remain buried under layers of sand, stone, and history.