Art & Tech

A New Video Game Explores Monet’s Masterful Use of Color by Placing Players Inside the French Painter’s Eyeball

The Master's Pupil is inspired by Monet's life and breathtaking colorwork.

The new independently released video game, The Master’s Pupil, hinges on an ailment that afflicted Claude Monet toward the end of his life. Around 1913, while in his 60s, the French painter developed cataracts, which increasingly affected his ability to paint. Colors, he wrote in a letter, “no longer had the same intensity for me,” while his canvases were “getting more and more darkened.”

Refusing surgery for the longest time, Monet would cope by strictly ordering the colors on his palette and labeling his tubes of paint. He also wore a huge straw hat outdoors to deflect the glare from sunlight. But what if, The Master’s Pupil proposes, the artist had some extra help?

Created by Australian designer and developer Pat Naoum, the 2D platformer game places its players inside Monet’s eyeball, sending them on an adventure dotted with puzzles based on color, space, and physics. By completing a number of these tasks, players are also helping to complete the artist’s works.

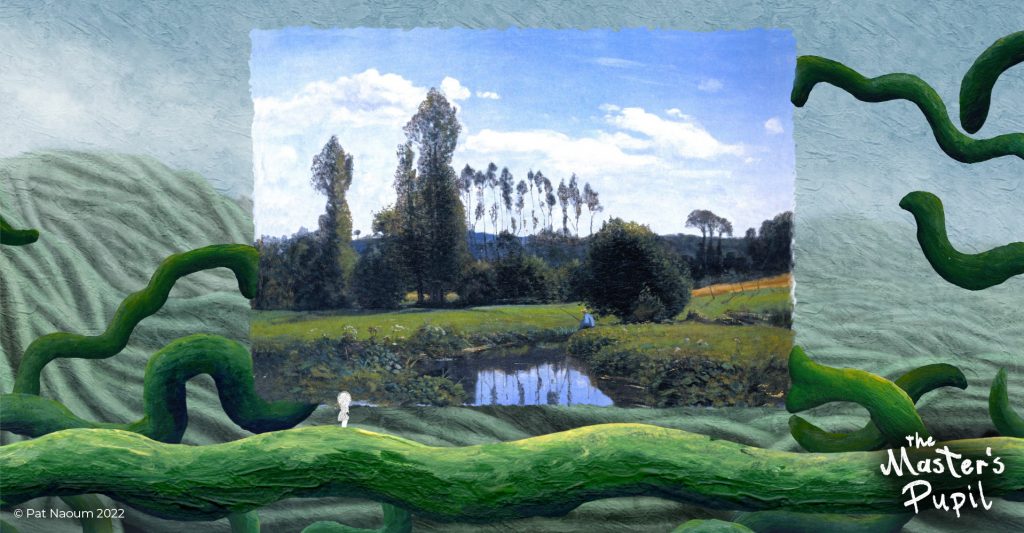

A scene from The Master’s Pupil. Photo: © Pat Naoum.

Naoum’s decision to focus his first game on Monet was down to the painter’s masterful use of color and his grappling with a disease that dramatically affected his work. The Master’s Pupil, then, is as much an art puzzle as a journey mirroring Monet’s life, hardships, and losses.

“It was an interesting process of adapting a real-life story into a game,” Naoum told Artnet News. “I had to get to know the beats of his life in great detail, which in turn created the levels’ arcs. It did require looking at his artworks quite deeply—not only at their style and colors, but also the context of them in his life.”

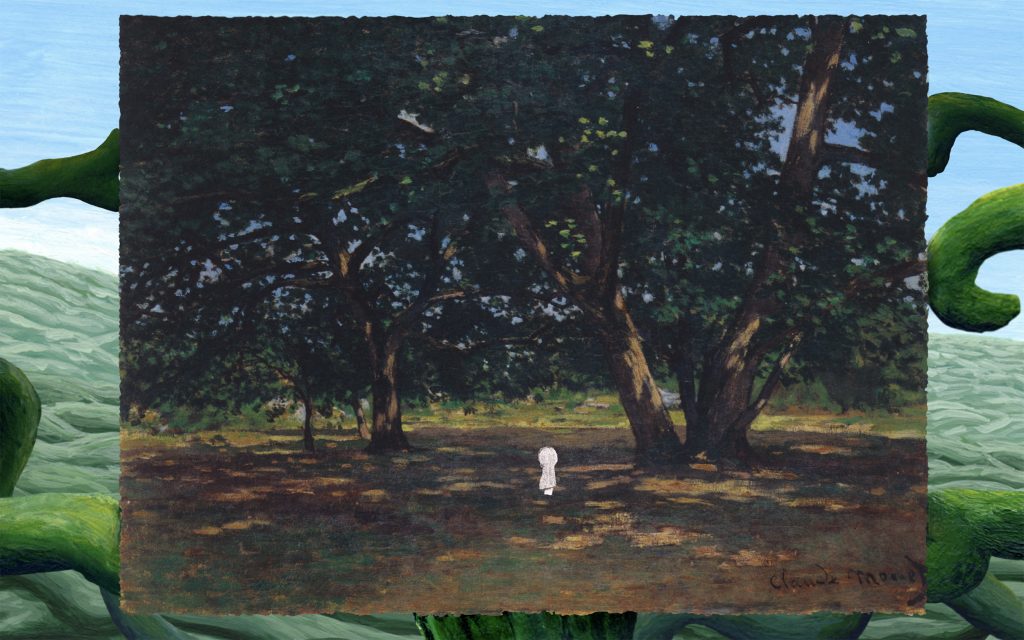

To progress through the game’s 12 levels, players run or jump along vines—in an echo of Monet’s love for nature—transporting colored balls or coating their avatars in particular shades in order to clear their path. At points, players get to traverse the landscapes of Monet’s paintings such as Still Life with Bottle, Carafe, Bread, and Wine (1863); at others, moving an object, say, helps arrange elements in the artist’s works including Woman with a Parasol (1875).

A scene from The Master’s Pupil. Photo: © Pat Naoum.

True to his background in art and film, Naoum opted to hand-paint the game’s environments and visual assets, lending the proceedings a charming and occasionally cinematic feel. “It was important to me to not only match Monet’s style, but also the texture of real-life paint to match the real-life paintings in the game,” he said.

The iterative process involved first designing each puzzle, before screenshotting the shapes (to preserve their proportions), arranging them in Photoshop, and printing them on paper cards that Naoum painted directly onto. He then scanned the paintings using a film negative scanner to capture the images in high resolution.

Hand-painting took up more than 2,000 hours—and all before Naoum had to teach himself how to code to program the project. “I still find coding hard, being so different from the basic visual thinking that I’m used to,” he reflected. “But I got there!”

In all, Naoum spent seven years developing the video game, supported by a grant from Screen Australia, the governmental body that supports on-screen production. In 2022, he began documenting his creative process on TikTok; by the time the game was released on Steam in July, it was on the wish lists of some 20,000 players on the platform.

Screenshot from The Master’s Pupil. Photo: © Pat Naoum.

For Naoum, the project has been as much a crash course in coding and game development as it was in Monet’s life and the breadth of his colorwork.

“When Monet painted, he would be very careful about the colors he mixed—so much so that it became a central part of the puzzles in The Master’s Pupil,” he said.

What players won’t find in it, though, is any hint of black. Fitting for an artist who painted the light, Monet was not a fan of the color.

“I learned a ton about Monet, but what often comes to mind is that he never used black paint,” Naoum added. “So known was it that at his funeral, his friend removed the black shroud over his coffin and said, ‘No black for Monet!'”

More Trending Stories: