Art World

15 More Globetrotting Art-World Figures Tell Us About the Best Shows They Saw in 2018

Lisa Schiff, Olga Viso, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev and others share their top show of 2018 in the second of our three-part installment.

Lisa Schiff, Olga Viso, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev and others share their top show of 2018 in the second of our three-part installment.

Artnet News

![]()

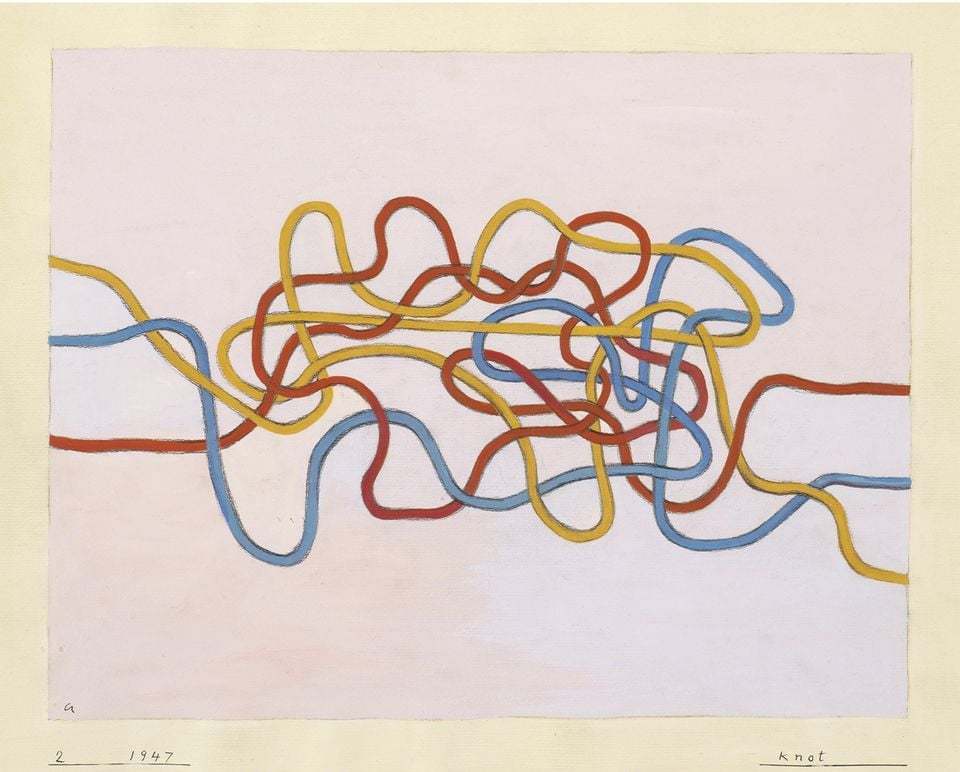

In the second of our three-part series (don’t forget to check out part one), a new batch of culturally conscious, world-travelling curators, dealers, scholars, and institutional directors tell us about the best shows and works of art they saw this year. The responses ranged widely, from Jack Whitten’s revelatory sculpture retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (chosen by curator Olga Viso), to Anni Albers’s quietly brilliant Tate Modern survey (select by Stephanie Rosenthal, director of Gropius Bau in Berlin) and beyond. Read on to see what our art experts had to say about art the world over.

Installation view “Mary Corse: A Survey in Light.” Courtesy of the artist and the Whitney Museum. © Mary Corse. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

I loved “A Survey in Light” at the Whitney, the first solo museum show of Mary Corse. Corse was one of the only women working in the Light and Space aesthetic that came out of California in the 1960s and was unknown to me before the show. Her work was delicate, contemplative, and poetic. I was shocked that she had been excluded from the Turrell and Irwin art-history nexus and felt it should have been a triumvirate with Mary as the queen. (Well, I was not really shocked, as it was definitely a cowboy culture.) Mostly, I was grateful and moved that she was now being written into the canon. I spent a long time hanging out in the space. It put me in the zone, and it also inspired me in my own practice. Brava! So thrilled this happened in her lifetime and grateful to the Whitney!

Dara Friedman, Dichter (2017). Courtesy the artist and Supportico Lopez, Berlin. © Dara Friedman.

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, The Instrument of Troubled Dreams. Oude Kerk, 2018. Photo: George Bures Miller

The exhibition that resonated most was Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s sound installation “The Instrument of Troubled Dreams” at the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam, though to call it an “exhibition” would undermine the work’s scope. Based on the church’s Vater-Müller organ, which was being restored at the time, the artists devised another organ with a soundtrack conceived for the building, which the public was invited to play. Twenty-five speakers connected to a mellotron (a mechanical precursor of the sampler) mixed different sounds—vocal, musical, mechanical, plus sounds from inanimate objects or nature—with sounds from, among other things, the aforementioned organ. The result is a haunting, resplendent soundscape of single and overlapping sounds (depending on how the instrument was played) that echoed and pervaded the vast space, activating personal and collective memories, sparking a rich plethora of associations and recalling the ghosts of history, recent and past. It was a masterful intervention that set the viewer’s imagination free, and respected the challenging, dominant architecture and dynamics of the space without being undermined by them.

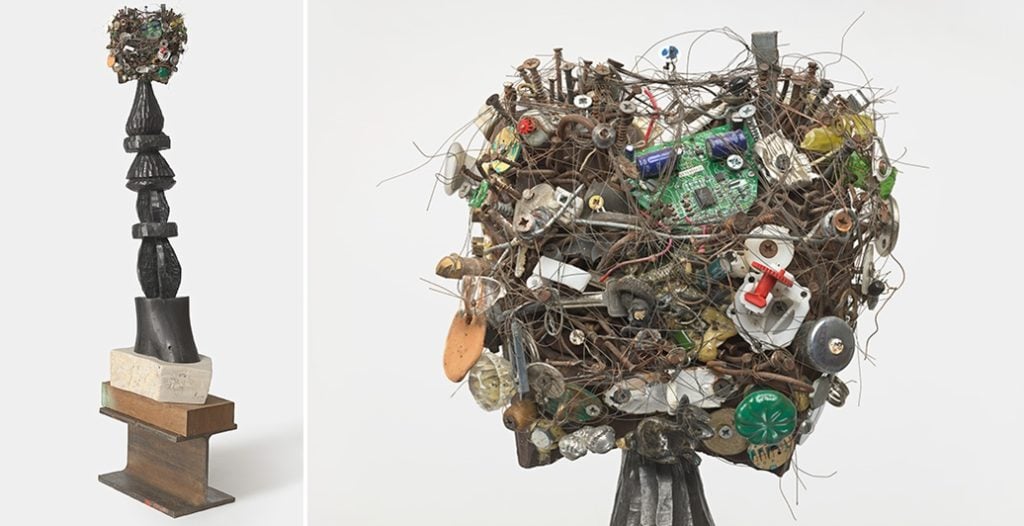

Jack Whitten’s Lucy (2011) and a detail from the same work. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Hauser & Wirth. Photography: Genevieve Hanson, NYC.

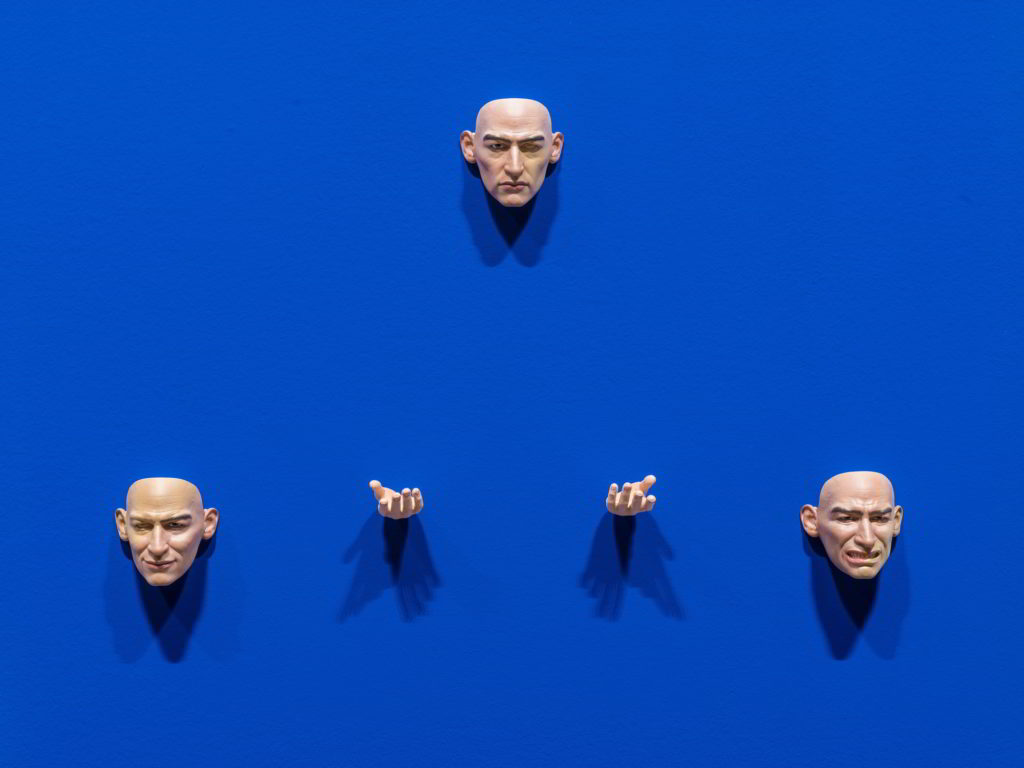

While it was a year for surveys of singular painters—most notably Hilma af Klint at the Guggenheim Museum and Charline von Heyl at the Hirshhorn in Washington DC—the exhibition that stood apart for me was “Odyssey Jack Whitten Sculpture: 1963–2017.”

Organized by the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Met Breuer with Whitten’s participation, the survey revealed six decades of the late New York-based painter’s little-known sculptural practice. Whitten’s sculptures—wood and metal constructions that frequently incorporate found objects he collected during annual sojourns to Crete—were strikingly paired with the artist’s Black Monoliths paintings, which give tribute to African American thought leaders. In addition, works of African and Mediterranean art that provided Whitten with vital source materials and inspiration throughout his life gave rich content to his art in ways that encyclopedic museums can astutely provide.

Pablo Picasso, The Dream (Le Rêve) (1932,) Private Collection ©Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2017

I liked “Picasso 1932—Love, Fame, Tragedy,” Tate Modern’s Picasso exhibition revolving around one year’s worth of work.

Paintings from Francisco de Zurbarán’s cycle depicting Jacob and his twelve sons, twelve of which are held at Auckland Castle. Image Courtesy Auckland Castle Trust/Zurbarán Trust. © The Auckland Project/Zurbarán Trust. Photo: Robert LaPrelle.

Still of “Island” at the Architecture Biennale in Venice. Photo courtesy of Cultureshock.

Installation view, “Matt Mullican: The Feeling of Things.” Courtesy of Pirelli Hangar Bicocca.

For me, this year’s standout show was “Matt Mullican: The Feeling of Things” at Pirelli Hangar Bicocca in Milan. It’s a huge space and there’s always the threat that it will overwhelm an artist, but in this case, it afforded Mullican the scope to explore, extend, and amplify the seriality and excess that is at the heart of his extraordinary practice. Including banners, works on paper, sculpture, video, glass, and the most incredible final room—which brought together rubbings and paintings at an exhilarating scale—the whole sprawling installation only served to reinforce the work’s already ambitious reach. Moving between scales in a way that brilliantly articulated Mullican’s preoccupation with the physical, symbolic, and immaterial registers of his “Five Worlds” project, it flickered effortlessly between the macro and the micro, the intimate and the monumental, the personal and the universal. Utterly breathtaking.

Anni Albers, Intersecting (1962). Photo by Werner J. Hannappel, courtesy of the Josef Albers Museum Quadrat Bottrop © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, 2018.

Saito Seiichi + Rhizomatiks Architecture, Power of Scale (2018). Installation view: “Japan in Architecture: Genealogies of its Transformation” at the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2018. Courtesy Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. Photo: Koroda Takeru.

One of my absolute favorites this year was the exhibition “Japan in Architecture: Genealogies of Its Transformation“ at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo. It featured Japanese building traditions dating from ancient building techniques up to the present. The exhibition was divided into nine well thought-out chapters that offered different ways to look at—and experience—Japanese architecture. The themes included wood as a building material, roof formations, and hybrid architecture. I was especially impressed by the exhibition design: it led visitors gently through each theme, creating genuine spaces of contemplation. The exhibition was great in content, curatorially clever, and went straight to one’s heart.

Yang Wei-Lin installing Ocean of Cloth Wheels (2018) at the White Rabbit Gallery.

Having seen many wonderful exhibitions this year, I decided to pick the most unprecedented and memorable—a show completely unlike the portrait-based aesthetic I am usually most drawn to. “Supernatural” at the White Rabbit Gallery in Sydney, Australia, offers an eclectic range of work by 31 contemporary Chinese artists. The theme is the landscape, the loose interpretations of which vary from depictions of the physical world to those of the personal inner experience of the artist. It brings together video installations, photography, sculpture, conceptual installations, paintings, and more into a vertical experience that evolves over four floors.

The exhibition opens with Li Shan’s Deviation (2017): 10 hanging creatures—part insects, part men—that we get to experience from all angles as we make our way up the stairs. It ends on the fourth floor with Yang Wei-Lin’s Ocean of Cloth Wheels and Floating Islands (both 2013–15), presented as an immersive installation of thousands of cloth discs dyed in shades of indigo that give the feel of a surreal underwater oceanscape.

Along the way, Sky (2015) by Yang Maoyuan is an installation of photographs of 35 skies commemorating Liu Zhongfu, a friend of the artist who was aboard disappeared Malaysian Airlines Flight 370. The photographs were made by friends of the artist from all over the world at the exact same time.

Installation view of Emilio Vedova “Absurd Berlin Diary ’64” at the Berlinische Galerie, Berlin. Photo by Michael Findlay.

Emilio Vedova’s Absurd Berlin Diary ’64 at the Berlinische Galerie in Berlin. Radical free-standing abstract paintings constructed in Berlin three years after the Berlin Wall went up. Fresh and startling.

Eugène Delacroix, Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1833–1834). Musée du Louvre, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais/Franck Raux.

Cécile B. Evans, Amos’ World is Live (2018). Courtesy of Art Night 2018.

Two of the many memorable shows I saw this year are, firstly, “Cécile B. Evans: Amos’ World Is Live” exhibition and performance, which was part of London’s Art Night. Evans filmed part of her work Amos’ World (2017–ongoing) in front of an audience with a full crew and cast (and puppets) with narrated action for the audience. It was at once moving, complex, and funny, and felt like being let in on a secret. The full exhibition in its completed form is now open at Tramway, Glasgow. I was also lucky enough to see the monographic exhibition “Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Once In a Lifetime” at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. It’s still on and is a phenomenal, truly once-in-a-lifetime show. You’ve got until January 13 to see it!

Alex Da Corte, Rubber Pencil Devil (2018). Courtesy of the artist and Karma New York. Photo: Tom Little.

This framed neon train, timetable-like sign [on the left] narrates Alex Da Corte’s amazing film Rubber Pencil Devil at the Carnegie International. I had the good fortune on a recent visit to his studio in Philadelphia not only to place an edition of the film, but also the sign itself, which changes font chips and messages and is as poetic as the film itself. What most struck me is that Da Corte’s film is not color corrected and I realized that this is his brush stroke. His high-keyed retail colors are so poppy and happy on the one hand, but they are about to tilt over into the acidic and rotten. It’s a dexterous balance on his part. I am truly blown away by the depth and range of his skills. Not to mention he is an authentic, beautiful soul.