Art World

14 Globetrotting Art Aficionados Tell Us About the Most Memorable Show They Saw in 2018

Pamela Joyner, Allison Zuckerman, and others share their top show of 2018 in the first installment of our three-part series.

Pamela Joyner, Allison Zuckerman, and others share their top show of 2018 in the first installment of our three-part series.

Artnet News

![]()

Hindsight often puts things into perspective, and as 2018 draws to a close, some shows linger in our minds more than others. To reflect on the year in art, we asked a well-traveled group of curators, museum directors, auction house executives, artists, and other aesthetes to tell us about the best show they saw in 2018. Their choices range from the sprawling debut of the Riga International Biennial to the much acclaimed Hilma af Klint retrospective in New York City, and beyond.

We’ve rounded up their responses in two parts—stay tuned for the second installment later this week and the third to follow.

Exhibition view of “Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture 1963-2017” at the Met Breuer, September 2018.

For me, the most memorable exhibition of 2018 was “Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture 1963-2017” at the Met Breuer. I am a longtime lover and collector of Whitten’s paintings. The show revealed that the key to unlocking the painting practice is indeed the experimentation Whitten engaged in every summer at his home in Greece when he assembled these sculptural works. The language embedded in the developer paintings, tessera works, and black monolith paintings is evident in their sculptural antecedents. From the sculpture one can also see more clearly Whitten’s interest in exploring every aspect of the materiality that one could possibly extract from the medium of paint. From this show I have found a new lens through which to see old favorites.

INTROSPECULATION (2018) from the series “Neo-Logos” by Annaïk-Lou Pitteloud. Photo © Ivan Erofeev.

For us the most memorable exhibition in 2018 was the Riga Biennial, curated by Katerina Gregos. It gathered the three elements we consider necessary to succeed in a quality biennial: 1. Quality works, and in this case Gregos even managed to go for lesser known artists rather than the usual suspects; 2. Coherence and consistency around its concept, which reflected on the phenomenon of change—how it is anticipated, experienced, grasped, assimilated, and dealt with at this time of accelerated transitions and the increasing speeding up of our lives; 3. The choice of locations created not only a deep connection between the works and the biennial’s concept, but also to the city, as all of them had a soul and a connection to the city of Riga.

I enjoyed it so much that we ended up acquiring three works on exhibition there for our collection.

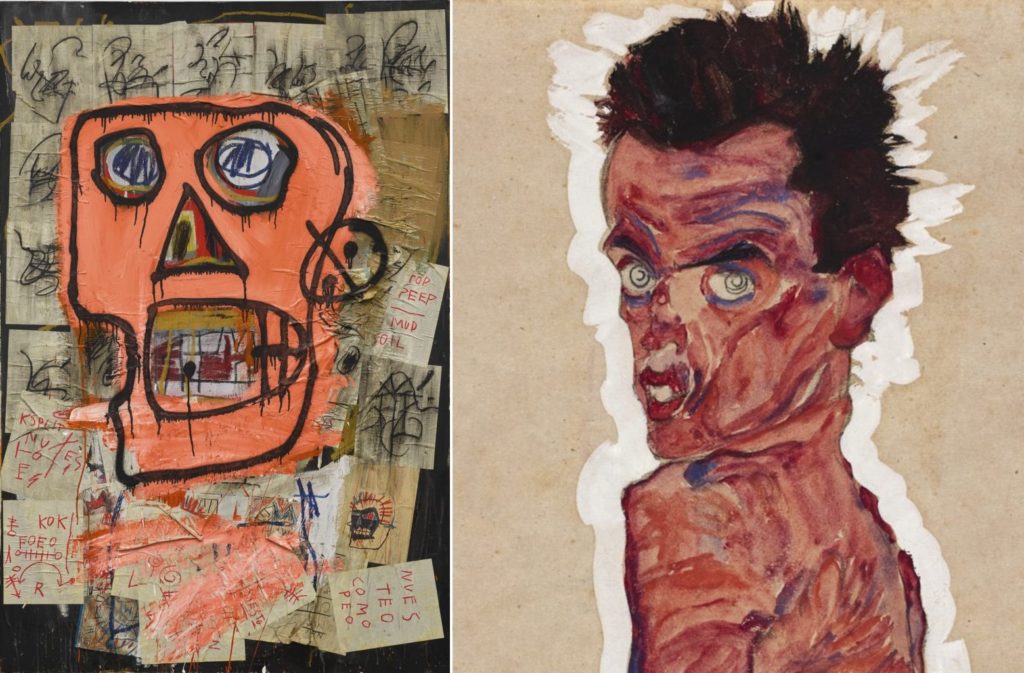

L: Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (1982). Courtesy of Sotheby’s. R: Egon Schiele, Self Portrait (1910). Photo: Galerie Sanct Lucas, Vienna.

What comes to mind is the dialogue between Egon Schiele and Jean-Michel Basquiat at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. Both exhibitions were monographic, survey-style exhibitions which were beautifully installed, expansive, and enthralling. What really struck me is that they both died at the same age and they shared an interest in anatomy and the body in various modes of being. In particular, they both painted hands in incredible and dynamic ways.

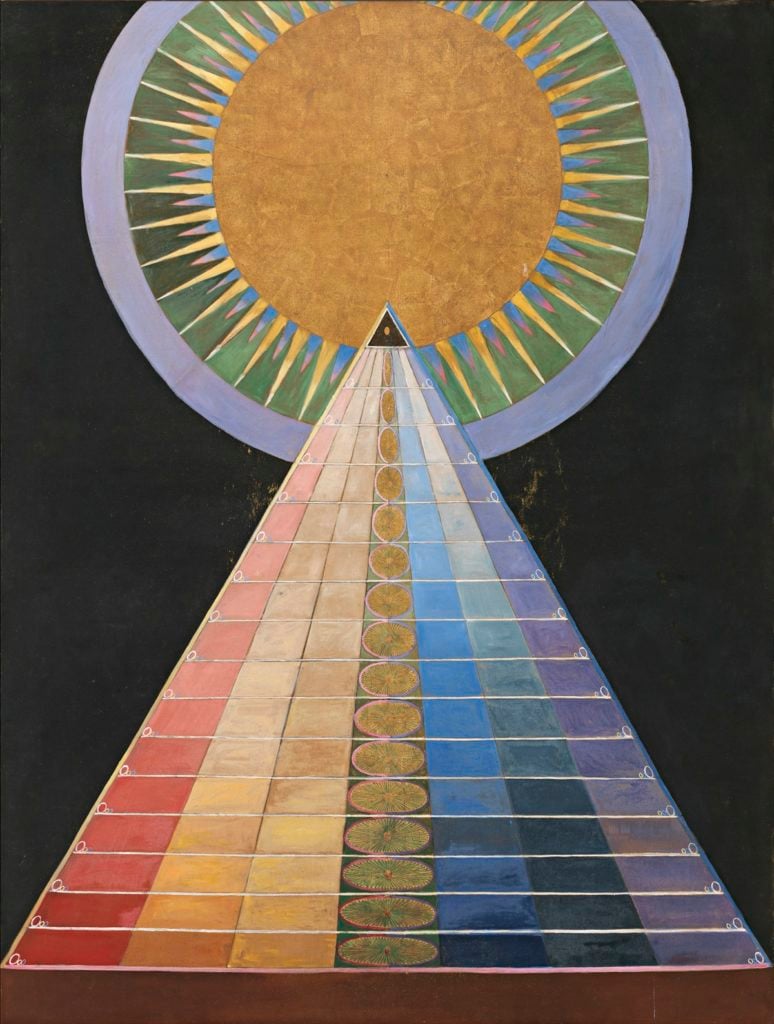

Hilma af Klint, AptarpiecesL Group X, No. 1, Altarpiece (1915). © Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk.

Of course, this exhibition is incredible for all of the reasons that everyone can’t stop talking about—a real revelation of an artist who created truly innovative work in modern abstraction well before the breakthroughs of Kandinsky and Mondrian. But what I’ve found most memorable about the exhibition is the story it tells about the penetration of Eastern thought into Western psyche as one key ingredient in the progress of modernism. Within af Klint’s work lies the first evidence of Eastern philosophy influencing Western art.

Joana Vasconcelos, Egeria (2018). Photo: Luís Vasconcelos/Cortesia Unidade Infinita Projectos. Collection of the artist. © Joana Vasconcelos, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2018.

Greedily, I’m sneaking in two for the price of one with Vasconcelos’s gargantuan, exuberant tour de force of an installation that snaked through the ginormous Guggenheim atrium, to be counterpointed on the upper level by Giacometti. An exceptional, telling exhibition of some of his most important sculptures, including all eight Women of Venice, it was daringly spare and pale as pale—possibly the most exquisite installation I’ve ever seen.

Cristoforo Savolini, The Madonna and Child. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The Otto Naumann Sale at Sotheby’s New York included 35 paintings from the dean of New York Old Master dealers, who was closing his Upper East Side gallery after 30 years. The show, which was on view for a week or so in advance of the auction, was an eccentric selection of works the dealer couldn’t bring himself to sell, or couldn’t bring any clients to buy. Naumann admitted that he couldn’t resist overspending for works he especially liked. “If paying too much is your only problem,” he said, revealing an old secret of the trade, “you don’t have a problem.” The fragmentary Madonna and Child by Christoforo Savolini sold for $137,500 (with premium), well above the $80,000 presale high estimate.

Anthony van Dyck, Charles I (1635-6). Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017.

One of the exhibitions that really stood out for me was the grand exhibition about the British king Charles I as an art collector. Charles had one of the greatest and most extraordinary art collections of his age. After the king’s execution in 1649, his collection got scattered across Europe. This exhibition reunited some of the greatest masterpieces of this collection for the first time. Works from Titian, Van Dyck, and Rubens were on show, just to name a few.

“Richard Prince: High Times” at Gagosian. © Richard Prince. Photo: Rob McKeever, courtesy of Gagosian.

This maximalist ouroboros of a show bursts with dichotomies. In a simultaneously aloof yet hot approach, “High Times” asserts that authenticity can coexist within a framework of appropriation, and that physical labor and technological reproduction are interchangeable.

Prince mines his history and ushers it into the present. He reclaims past drawings, photographs them, prints them, paints on them, photographs them, prints them… rinse and repeat. While this act of self-cannibalization can be deeply personal, Prince maintains distance. The figures themselves do not reveal emotional states, but instead relish in their intentionally confused forms of being printed and/or painted.

When viewers photograph these paintings, the works are transformed into a completely pixilated state: any difference between a painted stroke and a pixilated mark is obliterated. Because so much of my day to day is mediated through a phone screen, in which all imagery is translated into pixilation, I find that “High Times” could not be more relatable.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Constellations (2018). Courtesy of the artist.

One of the most fascinating, and shudder-inducing, experiences of 2018 was crossing the Pacific to visit the site-specific installation by filmmaker and artist Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Constellations, a commissioned project for the Gwangju Biennial. For this work, the artist transformed a former military hospital into a kind of film set, adding lights, projections, and objects with a subtle, poetical touch. This was the site where injured and tortured students and citizens—victims of the 1980 Gwangju incident—were hospitalized. Laying dormant and devastated for over a decade, it represented a tragic memory intimately connected to Gwangju. The artist strongly encouraged us to visit after dusk, allowing his work to evoke the presence of those no longer here, like ghosts.

František Kupka, Disques de Newton (1912). Philadelphia Museum of Art © ADAGP, Paris 2018.

This show knocked me out. In many instances, particularly in his early work, he wasn’t just a contemporary of Kandinsky, but rather a true peer having made spectacularly dynamic canvases with a real compositional intelligence and nearly stellar explosions of color. The exhibition was exhaustive, laid out over two floors and I was surprised at how well the quality was sustained. With an artist like Kupka, whose works we mostly see on the market and are of inconsistent quality, it’s hard to form a true appreciation of his oeuvre.

Installation view of “Danh Vo: Take My Breath Away” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.” Photo: David Heald, ©Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2018.

For sheer surprise—which contemporary art offers me less and less frequently—nothing topped Danh Vo’s Guggenheim Museum retrospective “Take My Breath Away” in New York. Born in Vietnam and raised mainly in Denmark, Danh Vo offers historically, politically, and personally freighted new takes on the readymade and the found object. An old manual typewriter placed askew in one of the museum bays? A snooze—until the label identified it as Ted Kaczynski’s, acquired by the artist (like many other items re-situated here) at a federal trial evidence property auction. No show cut so cleverly against political correctness with such a gain in political gravity.

Exhibition view of “Hello World. Revising a Collection.” Agora Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin, 2018 © Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Thomas Bruns.

For me it would be “Hello World,” the audacious and revelatory summer exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, which attempted to recast the museum’s entire collection with a more global outlook.

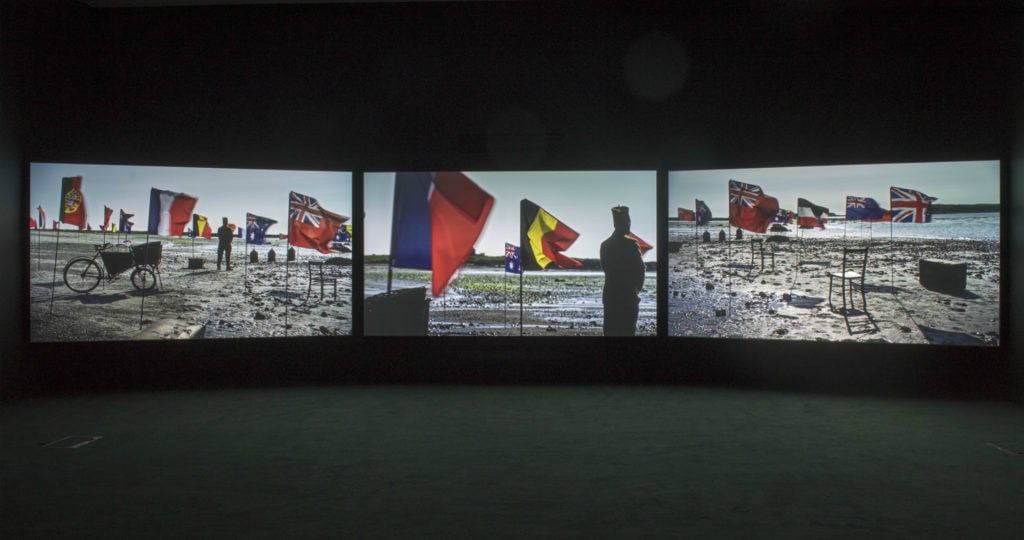

John Akomfrah, Mimesis: African Soldier. Courtesy of Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery.

The single most memorable thing I saw in 2018 was John Akomfrah’s Mimesis: African Soldier at the Imperial War Museum in London. It’s not easy to make profoundly research-based work that is just as deeply engaging on a human level. Too often what’s most impressive about archival finds can make the work hermetic, geared to a specialist audience. Mimesis was so moving that I immediately emailed Lina and Ash at [the film’s production company] Smoking Dogs Films to say personally what it meant to me. They triumph at sonic and visual bricolage. I saw it with my 9-year-old daughter, who could grasp through their storytelling the idea that warfare is murder by another name, and that unspeakable sacrifices were made by people who won’t get credit as heroes but who acted heroically. We had a heavy conversation as you can imagine! Beyond its audiovisual power, it also demonstrated a model in British art co-commissioning, as a collaboration between 14-18 Now and New Art Exchange. It felt visionary.

Jasper Sharp, curator at the Kunsthistorisches Museum:

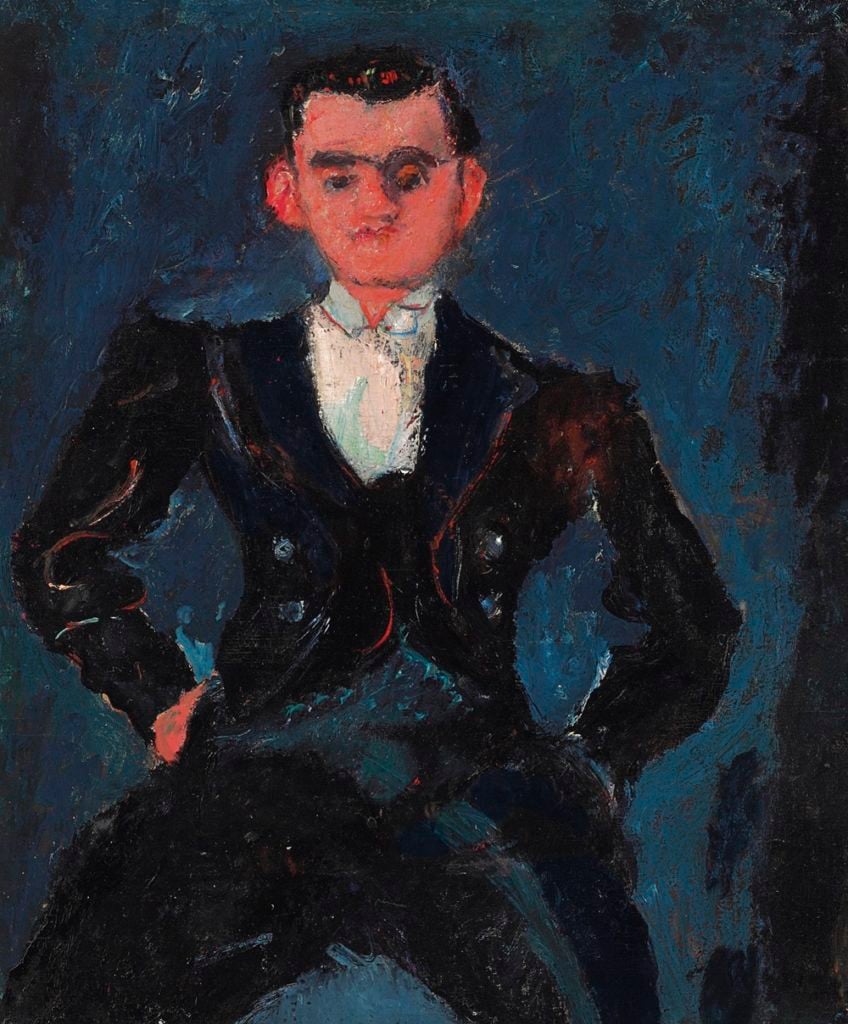

“Soutine’s Portraits: Cooks, Waiters and Bellboys” at the Courtauld Gallery

Chaim Soutine, Le Garcon (circa 1928). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

That rare thing: a perfect exhibition. Focused in size, revelatory in content, and with not the slightest piece of fat on it. Soutine seemed to grow a foot taller with each step you took.