Museums & Institutions

The Permanent Collection: Lyonel Feininger’s Childlike Steam Train

Albertina Museum curator Gisela Kirpicsenko discusses the importance of this seemingly innocent work.

What artwork hangs across from Mona Lisa? What lies downstairs from Van Gogh’s Sunflowers? In “The Permanent Collection,” we journey to museums around the globe, illuminating hidden gems and sharing stories behind artworks that often lie beyond the spotlight.

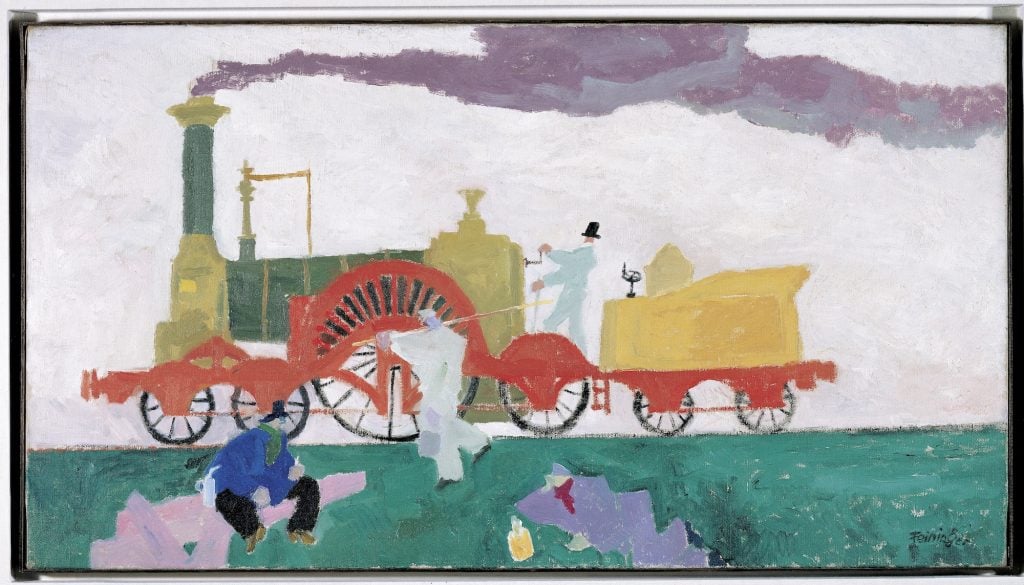

Lyonel Feininger, Die Lokomotive mit dem großen Rad (1910)

The Albertina Museum, Vienna

Chosen by: Gisela Kirpicsenko at the Albertina

What appeals to me about this painting is that it appears to have been made by a child. Of course, it was not, but with its seemingly imperfect forms, nervous brushstrokes, and collage-like character, it gives this impression. For me, it conveys Lyonel Feininger’s deep connection with his young sons or—to put it more generally—an ability to sympathize with a childlike state of mind.

While the style conveys an insecurity, we see a security of observation, unspoiled by realism but so full of attention. The locomotive, for example, is observed in every detail. Meanwhile the figures are rendered in a more general way formally, but their state of being comes through; we feel the weariness of the workers, the relaxed boredom of the figure lying in the grass, and the chatty posture of the man in blue.

During guided tours, visitors often ask who the people in the painting are and what they are doing. We are often asked about the construction and model of the locomotive. In one instance, a visitor was so captivated that they conducted independent research; namely, which model Feininger painted here. It’s the engine of the Iron Duke Class of the British Great Western Railway with a 2A1 axle arrangement.

I think the painting captures an ambivalent mood, one between movement and stillness. It’s not an easy mood, desolate and solitary, with hard work implied by the resting figures in the foreground. The hardship of the working class collides with the brightness of its colors and child-like rendering of the scene.

I think Feiniger’s ability to characterize figures through visual means, through exaggeration or distortion, comes from his profession as an illustrator. In this painting we can see it in the flatness of the figures. He also conveys a sense to movement where there is none, for the sake of telling or narrating a story. Feininger said that he sensed things in a stronger, deeper way than others. I think his figures bear an existential intensity.

—Albertina Museum Modern art curator Gisela Kirpicsenko, as told to Emily Steer