On View

A Moving Experience: Calder’s Forgotten Motorized Sculptures Whirr Back to Life at the Whitney

Even the artist's grandson was surprised when he saw the works in motion for the first time.

Even the artist's grandson was surprised when he saw the works in motion for the first time.

Julia Halperin

It’s hard to imagine Alexander Calder’s grandson Sandy Rower encountering anything that could change the way he thinks about his grandfather’s art. After 30 years at the helm of the Calder Foundation, he knows Calder’s work better than just about anyone else on the planet.

But an ambitious, yearlong effort to revive the artist’s rarely exhibited motorized sculptures, many of which have been dormant for decades, has done just that. After seeing the works in motion for the first time, “I was completely surprised,” Rower says. “You have to ask yourself a whole series of new questions.”

Alexander Calder’s Machine motorisée (1933). Photo: Calder Foundation, New York. © 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Viewers will have the chance to ponder these questions for themselves at the exhibition “Calder: Hypermobility,” which opens to the public at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art on Friday. The show allows viewers to experience Calder’s work as it was always meant to be seen: in motion. Every motorized work will be turned on—albeit temporarily, and sometimes only for a few minutes at a time—during the course of the exhibition.

Bringing Sculptures Back From the Dead

Perhaps the most novel element of the show is its emphasis on Calder’s lesser-known motorized works. The foundation teamed up with the Whitney to conserve eight of them ahead of the opening. Many of the works have not been shown in motion since Calder’s lifetime; for decades, they have sat dormant in the foundation’s storeroom. (Seven of the motorized works in the show come from the foundation’s own collection; one is from the Whitney’s holdings.)

Calder created the motorized works early in his career, primarily in the 1930s. “They are, in some ways, the first mobiles,” says the curator Jay Sanders, who organized the Whitney’s show (and is now director of the nonprofit Artists Space). “You see Calder working with abstract forms in motion. The name ‘mobile’ actually came from Duchamp seeing these motorized works.”

But these pioneering works have historically taken a backseat to Calder’s more recognizable mobiles and wire sculptures for several reasons: they’re rare (only 44 exist), they are strange, and many of them simply don’t function anymore.

When motorized works are shown, they are usually shown static, as they were in Tate Modern’s recent Calder show. Lenders are nervous to allow them to be turned on regularly for fear of wearing out the motor. (That’s part of why the Whitney show includes only motorized works from the foundation’s own collection, as well as that of the museum.)

A Conservation Revelation

Over the past three months, a team of conservators at the Whitney has been tinkering with small motors, belts, pulleys, and worn-down adhesive tape in an effort to bring Calder’s motorized sculptures back to life. All of the works have had their motors either restored or replaced for the show.

The process is “a bit like forensics,” says the conservator Eleonora Nagy. The team looks for clues Calder left behind, like arrows on the back of a sculpture that indicate which direction the objects should move, or small hand-carvings that prevented components from rubbing against one another when in motion.

Alexander Calder’s Half-circle, Quarter-circle, and Sphere (1932). Photo: The Whitney Museum of American Art.

Nagy says the project was also a welcome opportunity to remind people that conservators are more than wet blankets “stopping everything and saying it isn’t allowed.” In this case, her job was to allow Calder’s works to be used again—safely.

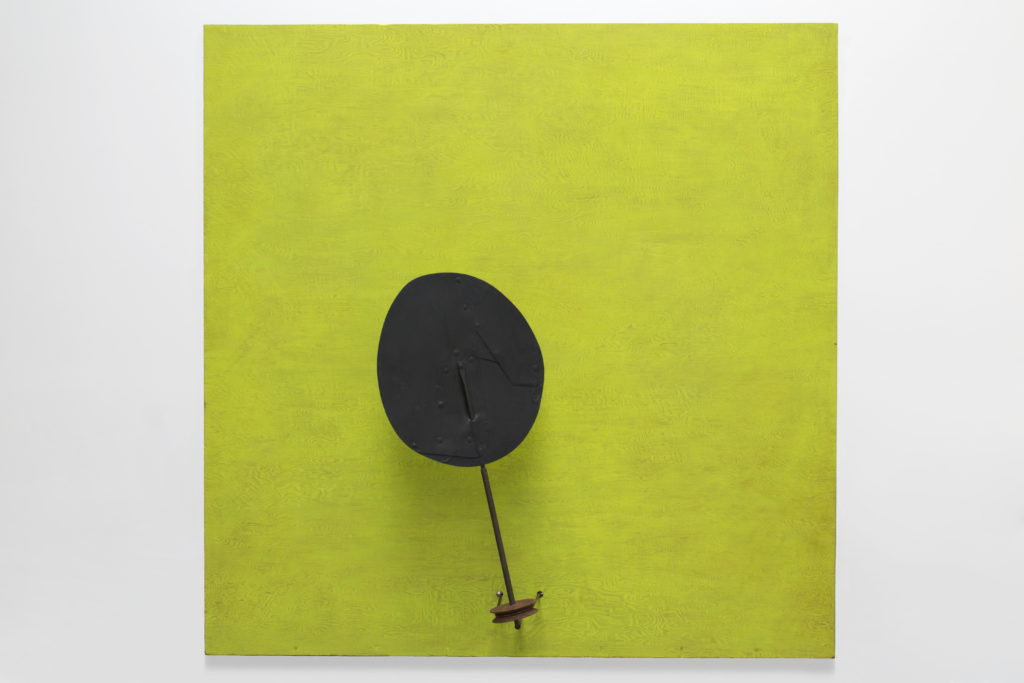

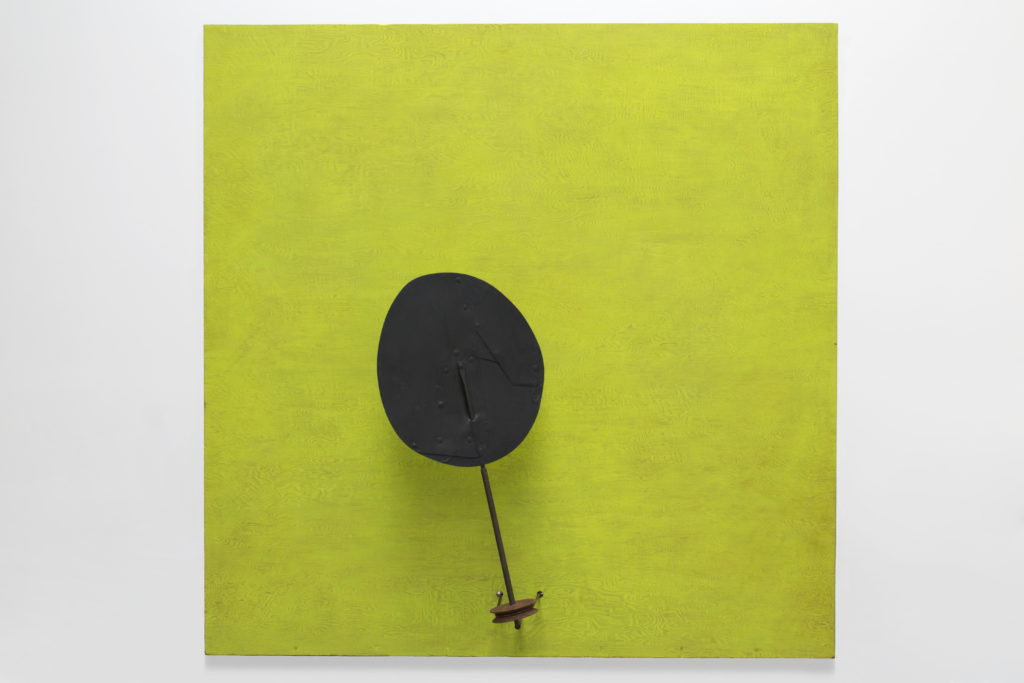

The process revealed some unlikely discoveries. Conservators uncovered a psychedelic green hue hiding beneath the yellow paint in Square (1934). It had been painted ahead of an exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in 1964; it hasn’t been seen or operated since 1965.

“Calder’s dealer at the time painted it [without his consent],” Rower explains. “He thought, ‘Nobody wants green, and yellow is a Calder color.’” More than 50 years later, it has now been restored to its original hue.

Another surprise? The pace of the motorized movements. Some elements that Rower thought would twirl at a zippy pace, “Josephine Baker-style,” instead rotate so slowly as to be almost imperceptible.

“You can’t anticipate the movement until it’s restored,” Jay Sanders says. “With every single piece, our predictions were defied.” He likens the patience required to view the motorized works to that required to listen to ‘60s Minimal music. “You have to slow down to properly perceive them,” he notes.

For Rower, the motorized works drove home an element of Calder’s practice that he is only now beginning to fully appreciate. “I always knew that Calder was not an entertainer, but you really see here that he is not trying to entertain you,” Rower says. “And if it’s not entertaining, then what is it? It’s not a sculpture, it’s not a picture—it’s an experience.”

“Calder: Hypermobility” at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, June 9–October 23

Video details, from top: S and Star (1941) set in motion, courtesy of the Calder Foundation, New York, © 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Red Panel (c. 1934) set in motion, courtesy of the Calder Foundation, New York, © 2017 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.