Art History

This 18th-Century Painting Could Rewrite Black History in Britain

New research brings to light the life of James Cumberlidge, a servant who became a trumpeter for King George III.

New research brings to light the life of James Cumberlidge, a servant who became a trumpeter for King George III.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

New research has revealed the fascinating life story of a once anonymous Black boy in a grand 18th-century English portrait by French painter Jean-Baptiste van Loo. Recently uncovered documents show that he went on to enjoy a career as a musician in the royal household of George III and may have even had the right to vote. The findings offer important new insight into the lives of Black Britons prior to the 20th century.

The 1739 family portrait was recently included in “Picturing Childhood,” an exhibition at the historic Chatsworth House in England. It depicts the prominent British architect Lord Burlington with his wife Dorothy, the countess, and their two daughters, Dorothy and Charlotte. Their names are written on a piece of paper on the floor in the painting.

Absent from this list is the identity of the third child in the painting, who stands to the far-right behind the countess’s chair. The boy carries a bundle of paintbrushes to pass her, having already provided the palette she holds in her left hand, marking her out as a keen amateur painter.

In 2004, the boy was wrongly identified by historian Richard Hewlings as James Cambridge because his name had been mistranscribed in a tailor’s bill from 1739 detailing clothes ordered by Countess of Burlington for her liveried servants, including James Cambridge “the black.”

Jean-Baptiste van Loo, Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and 4th Earl of Cork, and His Wife Lady Dorothy Boyle with Three Children (1739). Photo courtesy Chatsworth House Trust.

Thanks to new findings by Dr. Edward Town from the Yale Center for British Art, we now know that the boy was called James Cumberlidge, the name he used to sign several surviving notes and bills that he wrote for the Burlington household. Letters from the time also reveal that those familiar with Cumberlidge called him “Jim.”

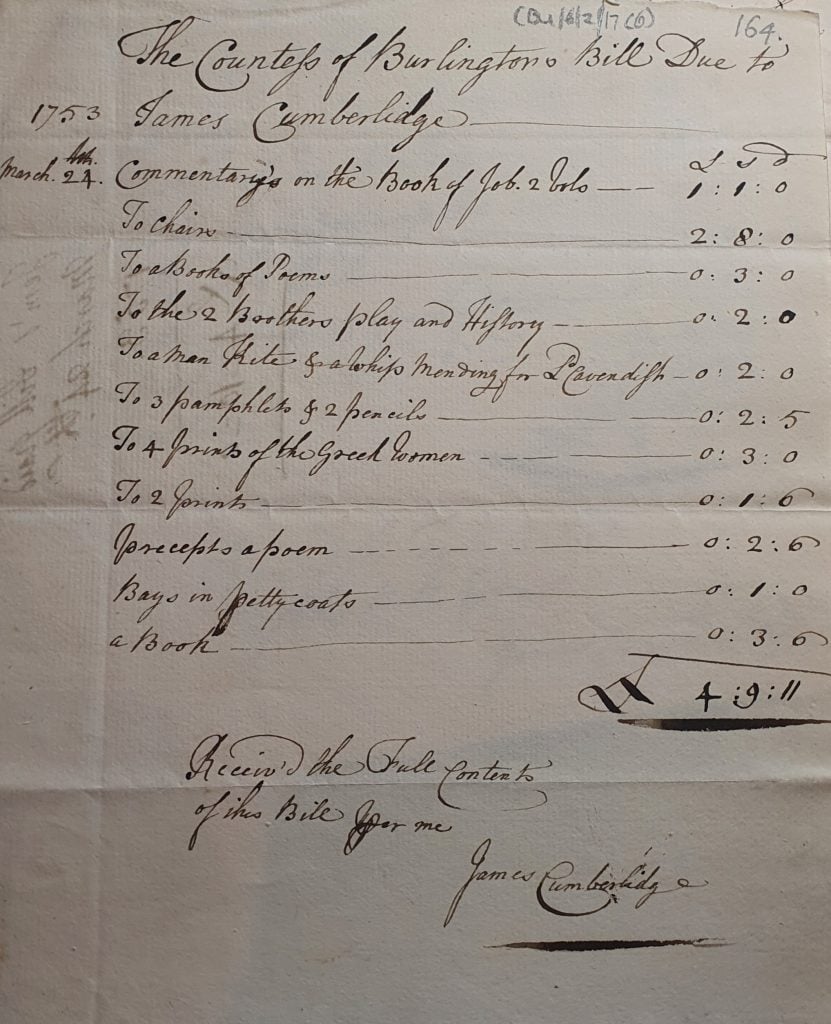

“Cumberlidge’s unusual name helps us recover his biography,” said Town, who rifled through the archives held at Chatsworth. While much of his childhood is still shrouded in mystery, records written by Cumberlidge show that, almost a decade after the painting was made, he was responsible for running errands for the countess, from fetching medicine and snuff to buying prints and getting books bound. At this time, the Burlington family lived between Burlington House in London, now home to the Royal Academy of Arts, and Chiswick House, which was then outside London.

“It’s clear that he was given a good amount of responsibility and that he was trusted as a preferred servant of the countess,” said Town. “This is not to say that his life was easy. His life was very much governed by the whims of this increasingly eccentric and erratic aristocrat.”

Record of James Cumberlidge’s expenses and wages from 1753. Image courtesy of Chiswick House and Gardens.

After the Countess died in 1758, her son-in-law, who was at that time Lord Chamberlain, the most senior officer in the royal household, found a job for Cumberlidge. He became a trumpeter for King George III for over two decades. Interestingly, there are at least two records of other Black trumpeters who were employed by the royal household in the 18th century. In the Tudor period, John Blanke was a trumpeter in the courts of Henry VII and Henry VIII and remains the only Black Tudor for whom an identifiable image has been found.

After about two decades in the royal household, Cumberlidge retired and moved to the parish of Walton on Thames in Surrey, where he died in 1788.

Town adds that there’s evidence to suggest Cumberlidge owned his house. “As a leaseholder, he was one of the very few Black Britons to control property and was presumably in a position to do so having enjoyed a salary in the royal household for many years,” said Town, noting that, as a property owner, “he may also well have been one of the first Black Britons to vote. There may well be more out there about him.”

Cumberlidge got married to a woman called Elizabeth though no record has yet been found to provide a date. This may be because there was a private chapel at Burlington House that had its own system of record-keeping. Cumberlidge’s son, also called James, was baptized in Walton on Thames in 1781. According to the census of 1861, he worked as an agricultural laborer.

“This pushes back against the racist narrative that the Black presence in Britain dates to post-Windrush,” said Town. “This story shows categorically that there were Black families living in England from [at least] the early 18th century through to the Victorian period.”

Garden front of Chiswick House, Hounslow, London, 1823. No.4 of Ackermann’s Repository of Arts. From the Mayson Beeton Collection. Artist Unknown. Photo: English Heritage/Heritage Images/Getty Images.

The portrait by Van Loo entered the collection at Chatsworth House after Charlotte Boyle, one of the two daughters, married the fourth Duke of Devonshire. Lord Burlington, her father, is notable for designing Burlington House and Chiswick House.

The latter property, a Neo-Palladian villa that is open to the public, recently initiated the Black Chiswick Through History project. So far, it has highlighted the lives of Jean Baptiste Gilbert, hairdresser to Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire and Joseph Casar, Lady Burlington’s footman and messenger. Like Cumberlidge, both men spent many years working for the Burlington and Devonshire families.

A longer essay by Edward Town will be published next week on the Chatsworth House blog. This article will reveal more information about how Cumberlidge may have joined the Burlington household, his brother Kitt Cumberlidge, his education, and a surprise connection with the famous actor and playwright David Garrick. Research into Cumberlidge’s life is ongoing.