There is something mythical about the sculptures of Thomas Houseago. They appear as if they were forged in an underworld, emerging from the earth as bent-up, long-limbed figures in bronze, wood, and steel. The artist once described his forms as “broken.”

It’s a word that most observers would not immediately associate with Houseago, a veritable art star who shows with some of the world’s top galleries; sells his art for as much as $1 million; and counts celebrities like Brad Pitt among his closest friends. Now, for the first time, Houseago wants to discuss another part of his identity: that he is a survivor.

Growing up in the 1980s in Leeds, West Yorkshire, one of the most violent regions in the U.K., the artist’s upbringing was shaped by severe traumas. They permeated his private life and have, he now recognizes, deeply informed his art practice as well.

Last year, following the death of an abuser, Houseago hit a breaking point. He stopped making art and experienced life-threatening depression. With the support of his loved ones, he receded from public life and set off on an arduous journey—one he knows may never be entirely complete—toward healing.

The process saved his life and transformed him as an artist, forcing him to rethink everything he has made and igniting in him a drive to create differently. Landscape paintings based on his visions during recovery are now on view at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Belgium (through August 1). Meanwhile, back in L.A., Houseago is slowly returning to sculpture—now with a style very different from the one that made him famous.

On a video call from his home in California, Houseago spoke for the first time about his mental breakdown and how he found his way back to art.

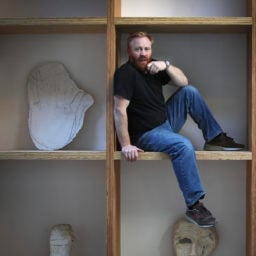

Thomas Houseago working on his balcony. Courtesy the artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels

I understand you are healing from a serious breakdown last year.

Yes—it was a very painful thing and hard to talk about, especially for the first year. Yet now, I believe it’s essential I do as there can be so much shame attached and I would like to dispel some of that. I have pre-verbal trauma that led to complex PTSD. It can be difficult to heal because it’s mostly situated in the body. It’s been there my entire life and I just didn’t know how to deal with it. I thought I was insane and I was too afraid to confront it, so I just ran. I thought if I ran far enough, I could escape. But you can’t—I learned trauma doesn’t age.

What was the timeline? I understand that you were in recovery as the pandemic began.

It was a series of events: my mid-career show in Paris, which was the most important and triumphant moment in my life as an artist and yet also very intense psychologically, was happening as my relationship at that time was falling apart. Then, my father’s death in the fall of 2019 was the real catalyst. It was going to come eventually no matter what, but the death of an abuser is often a powerful triggering event. I had been doing years of talk therapy and somatic work, so I hoped I’d be able to “handle” it on my own as I always had, but it cascaded fast and got very dangerous—a life or death situation. I beat myself with a rock New Year’s Eve 2020, so I went into treatment in Arizona in January.

I was fortunate to get to Sabino Canyon in Arizona. Firstly, it was such a cosmically beautiful landscape and also, I needed serious scaffolding. That kind of work can be both terrifying and totally transformative. I did EMDR [eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy], somatic work, group therapy, and different modalities, but it was my work with neurofeedback and theta healing with Andréa Copeland and the Reiki work I did with Erika Everson that brought these vivid healing visions—some beautiful, some sublime, and some extremely dark. But I knew they were guiding me, and I began to journal and draw the visions. I knew they were going to be key in my recovery.

Over the 70-day period of treatment, I realized my trauma memories were harder, darker than I could have imagined, and that led to my system getting overwhelmed and my body beginning to intensely release in these spasm-like episodes, so I needed continued intensive treatment back in California.

I remember flying into L.A. in March 2020 and everyone was wearing masks and I was convinced it was a hallucination—totally psychedelic. I then went into treatment with Danny Smith, which was an incredible blessing with his team. Eli Machen was my trauma therapist out in Malibu. I began to unlock miracles in my recovery. It saved my life, and as terrible as COVID has been, it allowed me time to reassemble my being to begin healing more deeply.

“Vision Paintings” at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. Photo credit: Allard Bovenberg

Was it hard to make art at the time?

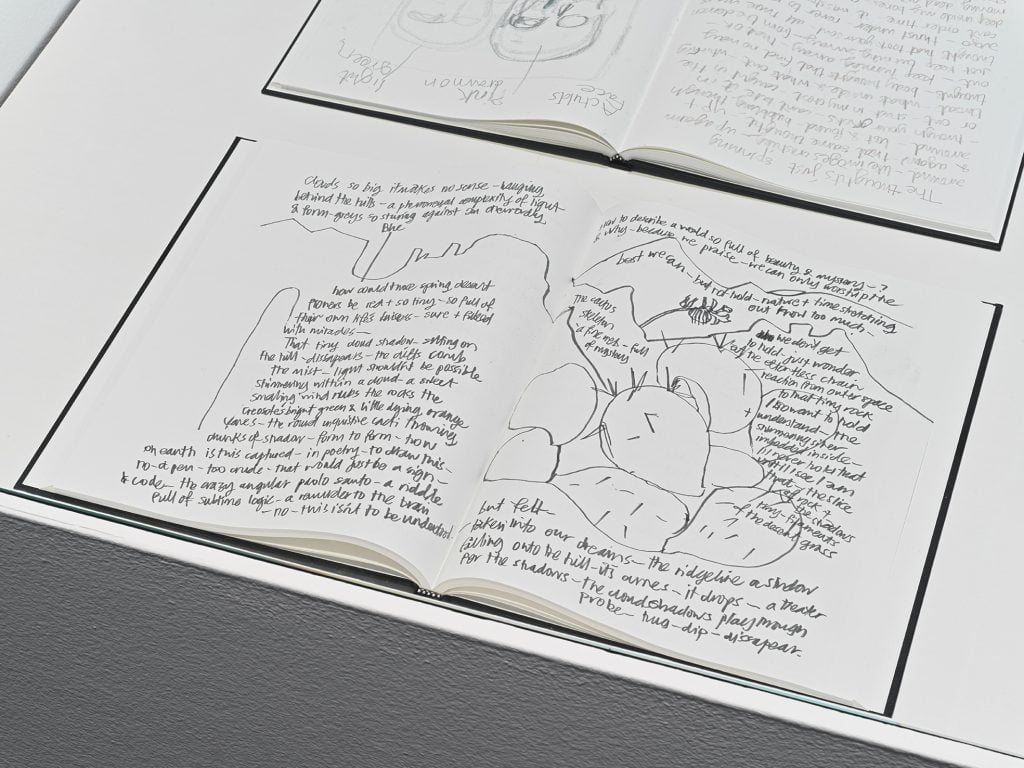

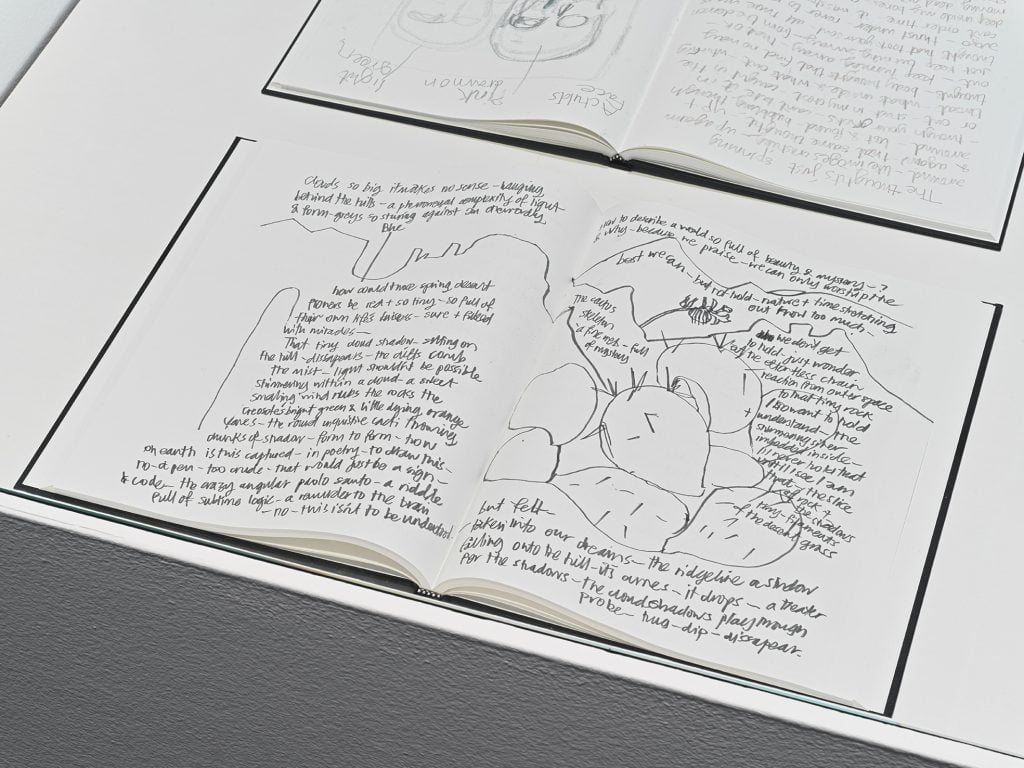

In Arizona, I had a journal for writing and ink and paper, which I used to note down and draw the visions I was having. But “art” as I had known it seemed impossible, that life seemed distant—even gone. I realized art had been at times a trauma loop. In my attempt to somatically, through sculpture, release the trauma, I was simultaneously re-traumatizing myself. It was only when Danny and Eli began to lead me back that I could reframe art. Flea [Michael Balzary from Red Hot Chili Peppers] also so beautifully supported me, and together we trail-ran. Flea helped guide me into this sacred and healthy space where creativity and nature meet a dialogue with something greater than oneself. And slowly, on those runs and mediations, the sublime became available in nature. I saw it in the moon, the sunset, the flowers—in just being close to the ocean in Malibu.

While I had wanted to start processing some of the scarier and more informative visions that related more directly to my trauma history, I started being able to weave in this new sense of nature as a healing and enlightening force. On some level I “knew” that could exist. It just hadn’t been truly accessible to my heart before. In that attempt to paint the beauty, art changed for me and became a friend—a way to access my higher self to process healing to find love.

A notebook from Houseago’s time in recovery, on view in “Vision Paintings” at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. Photo credit: Allard Bovenberg

So art was damaging, but also part of the healing process.

I now know with certainty that I wouldn’t be alive today without it. It was essential to me from the moment I could draw as a little guy. It was a safe space—a place I could escape, an activity like meditation that always guided me to my higher self. Yet it became de-stabilizing as I used it to dig deeper. My own work began to horrify and shame me, and I was acting out.

Yet looking back, I now have so much more empathy for myself and see a real bravery: a vulnerability in “daring” to make that work. Maybe some people received that work as bombastic, macho, “expressionistic,” “primitive,” or angry—as if I was this art-star asshole guy—I get it. I hated myself at that time too. Though, I see now that I was trying to describe and process trauma, my abuse. I look at some of the sculptures now and it is heartbreaking.

Organised by Public Art Fund and Tishman Speyer. On view at Rockefeller Center Plaza, April 28—June 24, 2015. Photo credit: Jason Wyche, Courtesy Public Art Fund, N.Y.

I was touched to see the Edvard Munch references in your new work. He said, “Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder…. My sufferings are part of myself and my art.”

When I was young, Van Gogh and Munch were important members of my fantasy artistic family. I love this almost pagan worship of nature in their work and that their struggle with trauma, addiction, mental illness was set against nature—nature as a regulating spiritual guide. But I think we have to be careful about romanticizing trauma or viewing it as essential to all art. I think it is often more crippling, limiting, and crushing. Trauma has to be taken way more seriously, and its impact on us personally and socially. I see that clearly, the terrible patterns of trauma being handed down and misplaced. I was locked in a much less creative space when living in my trauma. Now I’m much freer living with it—not in it.

And now you are in a whole new chapter of work—a lot of it is vibrant and colorful, which is different.

Yes. I’ve begun to feel joy, a connection to a higher energy—in nature and relationships. I wanted to show that journey out of hopelessness—out of a place I didn’t think I’d survive, and I wanted to report back on that joy. I’m not perfect—I still make so many mistakes and lose my way, but I feel a deep connection to my children, to my group of male friends, to hope, and to finding true love and connection.

“Vision Paintings” at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. Photo credit: Allard Bovenberg

Were you nervous to show the new work?

Absolutely. Also, I was nervous to make them. I couldn’t believe I was painting hope—trying to capture beauty. It seemed absurd at times. I felt like I was meant to have died, or actually had died in a way. I had a dark joke: I felt like it was as if Kurt Cobain returned suddenly making sound bowl albums! Man, I wish he could have—it would have been beautiful, I’m sure. Like, I’m painting the moon out on my deck—what the fuck is this? Hope was hard for me to paint, to show—a lot of risk in hope!

Your work is very powerful and vulnerable at the same time. How do you navigate being vulnerable without giving too much of yourself?

I’m not naturally good at that. It’s been tough work maintaining and creating boundaries because for a long time my existence was without boundaries. In this next phase of my life, I’m aware the stakes are high and I have a sacred duty to my recovery and my children. I created a lot of chaos in my past and am grateful to be able to be in the process of making amends—cherishing what’s truly meaningful. Danny [Smith] taught me that if you’re too accessible, you can’t create true availability to the things and people you love. I also have a very tight male group of creative, healing, incredible humans, so in being able to seek help and talk things through with them, I’ve built safety.

There’s this Death of Marat painting in your show, inspired by Jacques-Louis 1793 painting of the murdered French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat. A piece of paper in his hand says, “I have a right to your help.” I was thinking about that line when you were speaking about your group of male friends supporting each other. I was thinking about how being a white man in society right now is complex.

I think white men are finally being asked to look at themselves, to begin taking account of evil, racist, sexist systems that benefit a white notion of power that is vile and corrupting. My journey as a white male growing up within the class system in the U.K., before moving to the race-based, oppressive system in the U.S., has been really informative. Oppression is artificially manufactured for power and wealth. It’s important to remember the old colonial maxim: divide and rule.

In English music that is based on the white class experience—the trauma experience of the North [of the U.K.], for example, in Joy Division, The Smiths, or The Beatles—you can hear these artists revealing and processing this violence. I often think of the great Sex Pistols line, They made you a moron, A potential H bomb. I felt like a ticking bomb. The ability to access extreme violence as a solution is what those in power want and need—it is the Orwellian idea that those in power sleep peacefully only because rough men stand ready to do violence on their behalf.

This system of oppression and violence is deeply rooted in white culture, and in America, it’s particularly on vivid display. I’m always surprised when white Americans are shocked to see Black people brutalized and murdered in cold blood by the police. Violence is programmed in us as whites, which is why white people have not yet been able to mobilize. Where are the 10 million or 20 million white people marching on Washington demanding safety and justice for Black and Brown people? Slavery was a crime against humanity that was never properly acknowledged—that wasn’t accepted by whites. Thus, we haven’t been able to even begin a process of ownership, to make amends, to create social healing. Until we do, we continue to be accessories to a crime against humanity—it’s that simple.

If white people thought for a second their children might very possibly be brutalized, violated, killed going about their everyday life by police, by gangs, by desperation, there would be a revolution, blood would run in the streets. If we aren’t jumping into action, into amends, and reparations, then we are still accessories to a crime, and it is hellish. It’s the issue. I think white people have to take account of their passed-down patterns and traumas and start dismantling this horrible, poisonous system. There are glimmers of hope, cracks in the veneer, but we need strong mobilization because it’s a white-created problem, and those white systems are powerful.

“Vision Paintings” at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. Photo credit: Allard Bovenberg

Do you think there is not a lot of space right now to speak about trauma as a white male?

Well, there’s a lot of space to talk about anything as a white male, yet a deep fear about vulnerability. Particularly around weakness and sexual trauma, because it’s shameful and emasculating—two things that horrify white men. They say a physical attack is an attack on the body and on the nervous system and a sexual attack is an attack on the soul. It cut me off from my own soul and there is so much denial and gaslighting. It’s still a taboo, and because of that, there is no healing room. I saw how that can create a monster. I saw it in myself.

As I was going through my [recovery] work, a very dear friend of mine, Saul Fletcher, who was from a very similar background to me in the North [of the U.K.], unbearably unleashed his trauma on [his then-girlfriend] Rebecca [Blum] and [both of their] children. It was horrifying violence, such a loss. And of course I knew the loving, kind, creative, and gentle soul that Saul also was, and I couldn’t help but feel if he had access to the help available to me it was avoidable, and I was so deeply upset by the reaction to just wipe him out. I got why. I understand the urge, but it robbed the situation of its complexity and its opportunity for healing and understanding that can maybe prevent these situations.

People were upset by the way that the murder-suicide was covered.

I’ve lost two dear, dear friends from the North who seemed like they had “escaped,” who had potential to thrive and to do incredible things. The beautiful Michael Stanley [the U.K. gallery director, curator, and Turner Prize judge who died by suicide in 2012] and then Saul Fletcher. Two totally different situations, but I believe unresolved trauma was the key in both cases.

I think both those deaths should and could have been used to talk about trauma, about systems of recovery and help, about how dangerous isolation and PTSD are. If you are brought up in those contexts and periods in the North, you are on a fuse. I believe we were brought up to kill, either ourselves or others. When that happened [Saul Fletcher’s death by suicide and Rebecca Blum’s murder], I felt the coverage and the statements all should have had more compassion for the children involved. An opportunity to talk about addiction and trauma with compassion which could allow an opportunity to heal. I’m not abdicating his responsibility—what he did was horrifying. But I just think in the rush to be morally and politically outraged and “right,” we lost an opportunity to have discussions that are desperately needed.

We need to be able to speak about things with more nuance, I agree. Often these narratives lose that nuance when the situations are complicated.

It seems humans have a hard time living in the gray. In the vulnerability of that mystery, we can jump to oversimplify, and I think it would be wonderful to slow down and celebrate the mystery. Just that this cosmic entity, the sun, touches us perfectly every morning to wake us and the trees and flowers is already ample proof we live in something extraordinary. In Arizona, I’d listen to Bach as the sun came up in the canyon and weep that the music was also a sunrise.

Installation view “Almost Human” at Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 2019. Photo credit: Pierre Antoine

The Australian musician Nick Cave wrote a song for you on his new album. Can you tell me about that?

I have huge admiration for Nick and so much love for him, Susie, and Earl [his wife and son]. I think he is a genius and also a wonderful friend—so it’s a blessing. He was very present during some of the times I felt hopeless, and that I had lost my ability to make art. I had no idea who I was without it and he lovingly prompted me back. He made a deal to write me a song if I made him a drawing, and he sent me “White Elephant” one morning, which was still a poem then. It blew me away, activated me, and made me weep. I saw in that poem how he was able to channel a personal journey and fuse it with the socio-political. He saw the storming of the Capitol before it happened. Nick just has that extraordinary ability. As I painted and grew in confidence, we shared images and songs, and I watched and listened as the miraculous [album] Carnage took shape. I felt so grateful we got to share in a creative process together. It was the first time I’d ever done that with someone in another creative field. He used his art to help me. It was an astonishing act of love.

Did you give Nick any paintings you made in recovery?

Yeah, of course. I made him a moon painting and a flower, and the final work will be a sun!

“Vision Paintings” at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. Photo credit: Allard Bovenberg

How was traveling to your show in Brussels in the middle of a pandemic and that healing process?

I was lucky because I could get the vaccine in time to go and really experience the works as a group in that amazing museum. Also, one worry was that I had made them outside, and I could not see how it could work as a group indoors—if they would have a “logic” and seeing how they were curated was a big gift.

I was also lucky to have [my dealer] Xavier Hufkens, who followed the body of work closely and was extremely present and supportive during my recovery. I began to show him these early awkward weird drawings, and he could have just been like, “what the fuck, you’re a sculptor.” Instead, he responded with love, acceptance, and enthusiasm. I told Xavier at the time that I was making the works with him, for him, as he is an important audience—a part of my family, really. The museum and Michel [Draguet, director of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium] were also so generous and kind and welcoming.

Brad [Pitt] came with me to Europe to support and ground me—he is very present in those works and in that journey. We made a deal to stick together the entire time which was so lovely. He is so important to me on so many levels, has given me so much love, care, understanding, and permission. I’m eternally grateful to have that brotherhood. Afterwards we traveled to France and rested and unpacked for a week. I slept that week like I was in hibernation! It was a dream: we talked, ate, made art, listened to music, laughed, and kept dreaming and planning our sanctuary. It was a glorious and precious time.

It is an amazing feeling when you start to feel yourself turn a corner, I can imagine. Your brain starts to change, new pathways are made.

A lot of dealing with trauma is retraining your brain to feel new things, new neural pathways. I very rarely talk about this, but there is also a deep spiritual aspect. I always felt it, but before I didn’t trust it. Now, if I find the right meditative space and open up my heart enough and open up my physical being, I actually get a communication, a cosmic “download” that I can’t explain yet that profoundly nourishes and guides me.

You speak about childhood trauma—so I am curious if making work on the ground in this playful way was somehow a part of somatic therapy.

I was making these paintings outside on my deck. I did not have a great deal of space and there were strong winds in Malibu, so the elements are a real presence. I had to often lay the paintings down because the sundowner winds would knock them, hit me, and punch holes in the paintings. Pouring the paint and standing in the paint and working from the ground all were a part of what I needed to do, which was a complete immersion. In the last “vortex” paintings I did, you can actually see the slippers I wore throughout treatment in Arizona.

My son and daughter would help me and sometimes paint on them. Because of the pandemic, they were very involved in the making of the work, like returning to the domestic work system! The wind would blow the wet paint around at night and find sage flowers, sticks, dead bees, all kinds of things in the paint in the morning.

A view of Thomas Houseago’s studio in Los Angeles in 2010. Photo by Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

Do you think you’ll re-approach sculpture?

There’s a show at the Tate of Rodin’s plasters that are more experimental. You could say he is a “father” of modern sculpture, of assemblage. The director at the Rodin Museum asked if I would be willing to do something while it’s up, so Gagosian will show my sculptures alongside Rodin’s at their London space. I was very nervous at first about returning to sculpture. That show opens in September in London and I’m already working on sculptures for it now. It is really strange to see what’s coming out.

I’m also still working on this project at LACMA for the new building, my love poem to L.A. The last three weeks have been really exciting. This is all happening right now. Natasha, who runs my studio, says it took Rodin from the grave to get me sculpting again! I’m also super thankful to Gagosian and Amelie [Simier] for the prompt and opportunity. I work with two absolutely great galleries—both have been so solid and present and kind. When you are knocked down, you really see that. I rarely say it, and I should honor more the work and support they give me—I can’t do what I do without the superb team at my studio or the fantastic galleries I have.

How are these new sculptures different?

Me and the kids have this ritual where we go to the beach. We meditate, walk around, and collect things. It would be weird to pick up nice shells and not pick up the trash, so we have two bags—one for trash and one for shells. I would make these weird little assemblages with some of the interesting things we would find—little temples, these rock demons—mystical beings came into!

You seem to be building a different kind of practice now, one built around hope.

I’ve been talking a lot recently about how the world’s returning, how my career is returning, and how to not do it like before. How do we stay safe and intentional, and keep recovery number one? I think I have a mission now and that is to report on hope and that’s incredibly motivating. I’m realizing the true meaning of my life, of my work.

The art world has probably benefited, in some ways, from the slowdown too, to reboot itself.

The art world is a wild place. It’s also what I love about it. The art world is also, in some cases, responding faster than other institutions to race and to issues of gender. It has had to ask again what the meaning is of what it does without the endless art fairs, money, and hype. In the end, we are all children of the universe, no less than the trees and the stars. I believe that art has to have a relationship to meaning. It should not be stuff just being churned out. I get it. People do it and I have done it before at times. How do you pay the bills? But actually, if you live in abundance, you don’t need much. I did the whole show at the Royal Museums [of Fine Arts of Belgium] outside on a deck. It taught me if I have spiritual connection and meaning—that’s the most important—to try to be an ambassador of hope.

Please find an international list of mental health helplines here.

“Thomas Houseago: Vision Paintings“ is on view at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Rue du Musée 9/Museumstraat 9-1000 Brussels, April 22–August 1, 2021.