Art History

Did a Royal Painter Hide a Scandalous Secret in This Portrait?

For centuries, the clues to a Victorian-era affair have been hiding in plain sight.

When the grapevine is proving a little bare but a thirst for gossip takes over, why not uncover a centuries old scandal? Luckily for today’s art historians, some artists were pretty shameless about hiding a few salacious hints about their private lives in an otherwise perfectly respectable painting.

The latest discovery has been made by art historian Bendor Grosvenor during research for his book The Invention of British Art. He took as his starting point a rumored affair between the English portrait painter Sir Thomas Lawrence, known for his painting of Queen Charlotte, his first royal commission, and Isabella Wolff, who was once described by the landscape painter John Constable as an “intimate” friend of Lawrence’s. Wink wink.

Descriptions of their connection were only ever kept vague, owing to the fact that Isabella was married to Jens Wolff, Denmark’s consul in London.

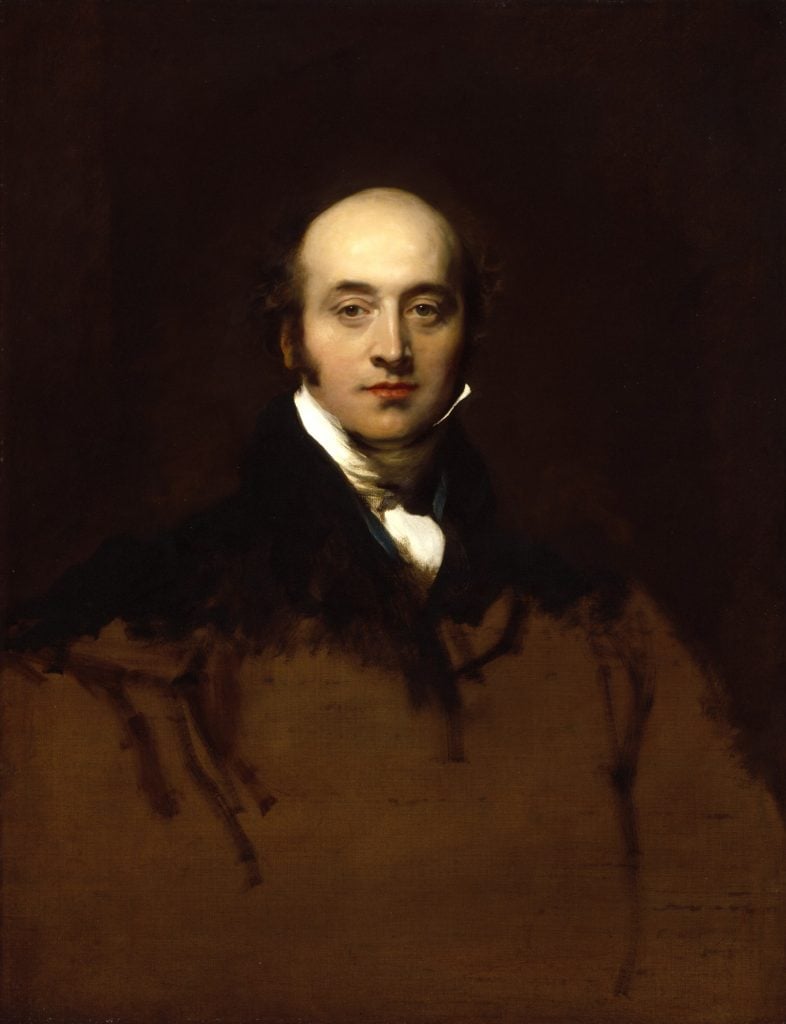

Thomas Lawrence, Self-Portrait (ca. 1825). © Royal Academy of Arts.

With correspondence between Lawrence and Wolff mostly destroyed by the executors of Lawrence’s estate, apparently to quell the tides of hearsay spreading fast through Victorian society, where else might surviving clues be found? Grosvenor says the real story lies hidden in plain sight, woven across Lawrence’s Isabella Wolff (1803/15), a painting that took him over a decade to complete.

Now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, the painting shows Wolff in a ravishing white satin gown and contemplating an image of the Delphic Sibyl by Michelangelo, copied from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Wolff herself is also presented in the guise of a sibyl, a term for female prophetesses from ancient Greek mythology. She wears an orientalizing turban, typical of how sibyls were depicted in the early 19th century.

Sir Thomas Lawrence, Isabella Wolff (1803/15). Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

It was Lawrence’s own words that inspired Grosvenor into action. He once told Wolff in a letter: “A really fine critic should, on looking at a picture, be able to assign a cause and motive for every form and hue that compose it, since nothing in it is a matter of accident.” Challenge accepted!

The most important clue is the apparent similarities between Wolff’s posture and the composition of Michelangelo’s lost depiction of Leda and the Swan, which we only know through copies. One such engraving belonged to Lawrence. But why insert a reference to the story of Leda? Though married, she slept with Zeus in the form of a swan and conceived two of his children. On the same night she conceived two more by her husband.

Could this story present a veiled reference to the paternity of Wolff’s son Hermann? It was previously thought that he was born in 1810, but this date has recently been corrected to 1802, which is just around the time that his mother met Lawrence. As it happens, Lawrence and Hermann were always very close while, after she divorced her husband, Wolff made the mysterious claim that she had never had a child with him.

Whatever the case, the split with Jens Wolff was acrimonious. In the background of the painting is a statue of Niobe, who was punished for her hubris by having her children slain. In this depiction, she appears to be pleading, most likely with Zeus to spare the last of her offspring. Grosvenor believes this may imply that Jens resorted to threatening Hermann when his marriage with Isabella fell apart.

So why was Lawrence forced to be so secretive about his rumored love for Isabella?

“I think he obviously had a lot to be fearful of, given the standards of the time,” Grosvenor told the London Times. “He’d just been made the king’s painter and had been given an amazing commission to go to all the capitals of Europe and paint the heads of state. He was about as big an art superstar as he could have [been] at that time. It would not have been good news to have a scandal out there.”